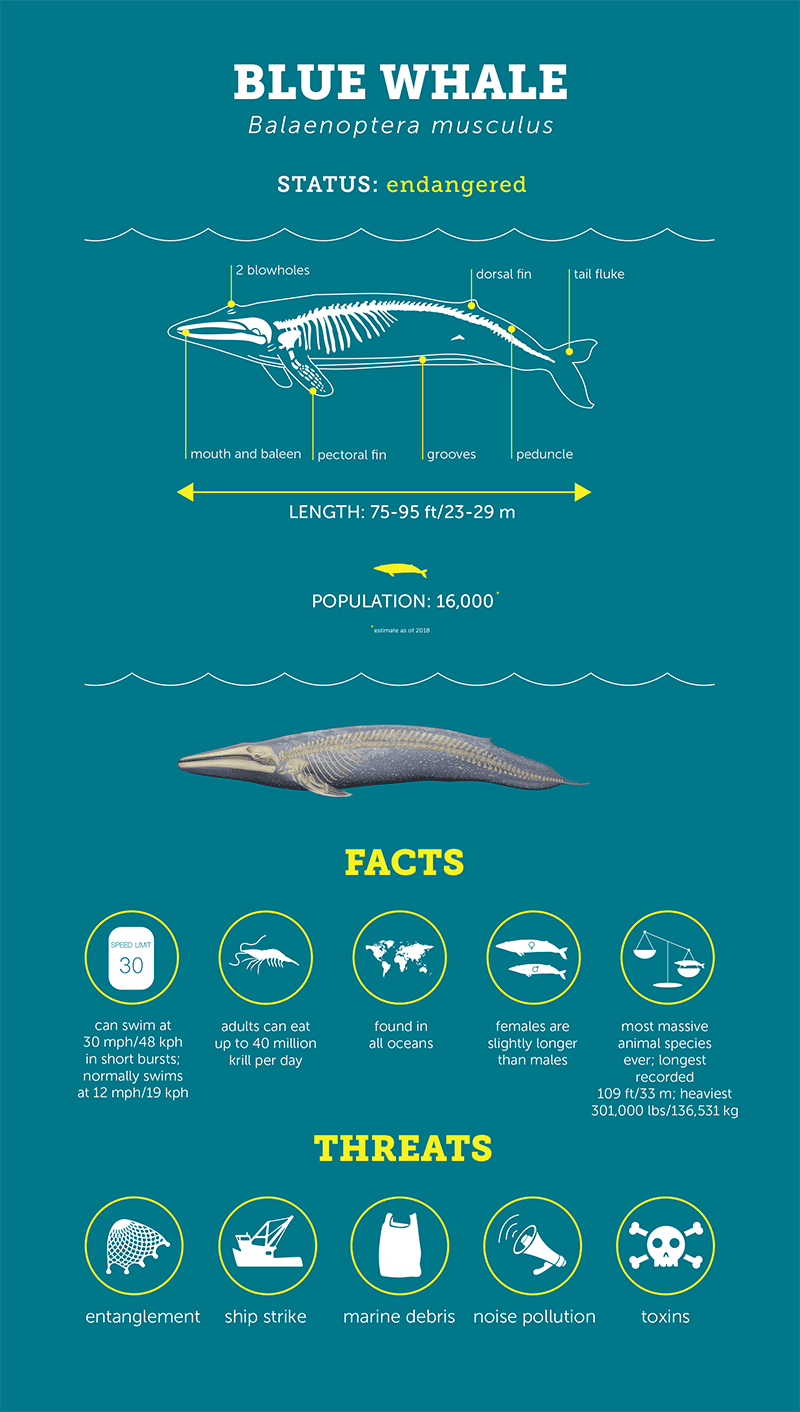

Blue Whale

The skeleton of a 66-foot (20.02m), rare, juvenile Blue whale, was acquired by the Museum after he was accidentally struck and killed by a 486-foot tanker and was brought ashore in Rhode Island in March 1998. He is the centerpiece of the Museum’s Jacobs Family Gallery.

How He Got Here

This blue whale (one of only 500 or so in the north Atlantic) was killed when he surfaced near Nova Scotia and was struck in the jaw by the tanker’s propeller. In stormy conditions, the dead whale was then struck by another tanker which unknowingly carried the whale across its bow into Narragansett Bay. It was then spotted by a pilot boat and identified. Towed ashore in Middletown, Rhode Island, it attracted the attention of international media and the scientific community. The National Marine Fisheries Service placed the skeleton in the care of the New Bedford Whaling Museum to be prepared for eventual display, free to the public, in what is now the museum’s entrance gallery.

Preparation and Display

The carcass of the 66-foot long male (estimated to be between 4-6 years of age) was initially delivered to the city of New Bedford’s landfill, where a small, dedicated group of trained volunteers carefully removed flesh from the bones. Biologist and renowned skeleton expert Andrew Konnerth was sought out to direct the process of “curing” and then reassembling the bones. He had assembled a number of whale skeletons in his career, but never a blue whale – the largest creature that has ever lived on earth. With the generous help of scores of volunteers and businesses in the community, sections of the carcass were placed in 22 specially built cages and submerged for five months in New Bedford harbor, where marine life continued the cleaning process. The bones were then delivered to the Museum’s courtyard for scrubbing, drying, sun-bleaching, and damage assessment.

At 18-feet long and one-and-a-half tons, the skull and lower jaw required a special shelter outside the Museum, which doubles as a workshop. The rest of the skeleton was brought inside the Museum to be restored and reassembled.

Interesting Details

A major challenge has been reconstructing the vertebrae that were badly damaged by the impact of the collision. Using blue whale bone samples borrowed from Harvard University, casts were made out of fiberglass and then painted to replicate the appearance of the original bones. Another challenge was the excessive oiliness of the bones, which caused them to turn deep yellow and smell unpleasant. After various experiments, this unexpected problem was resolved by soaking each bone in a biodegradable solution used to cure leather.