Art and Literature

Overview of Scrimshaw

The Whalers’ Art

Definition and Etymology

These days, “scrimshaw” is taken to refer to all kinds of carving and engraving on ivory, bone, sea shells, antler and cow horn.

However, in its original context as a traditional shipboard pastime of 19th-century mariners, scrimshaw refers to the indigenous, occupationally-rooted art form of the whalers, the defining characteristic of which is the use of the hard byproducts of the whale fishery itself – sperm whale ivory, walrus ivory, baleen (erroneously called whalebone), and skeletal whale bone, often used often in combination with other “found” materials. The origin and etymology of the term scrimshaw is unknown and has been disputed, but various forms of it – such as scrimsshander, skrimshonting, and skrimshank – began to appear in American whalemen’s parlance in the early 19th century. The term originally referred to the production of sailors’ hand-tools and practical implements, such as seam rubbers, fids, belaying pins, and thole pins, mostly made for the ship during working hours; but it soon came to signify objects made by whalemen–and, to a lesser extent, by tars in the naval and merchant services– primarily for their own recreation and amusement, intended mostly as mementos for folks at home.

Materials

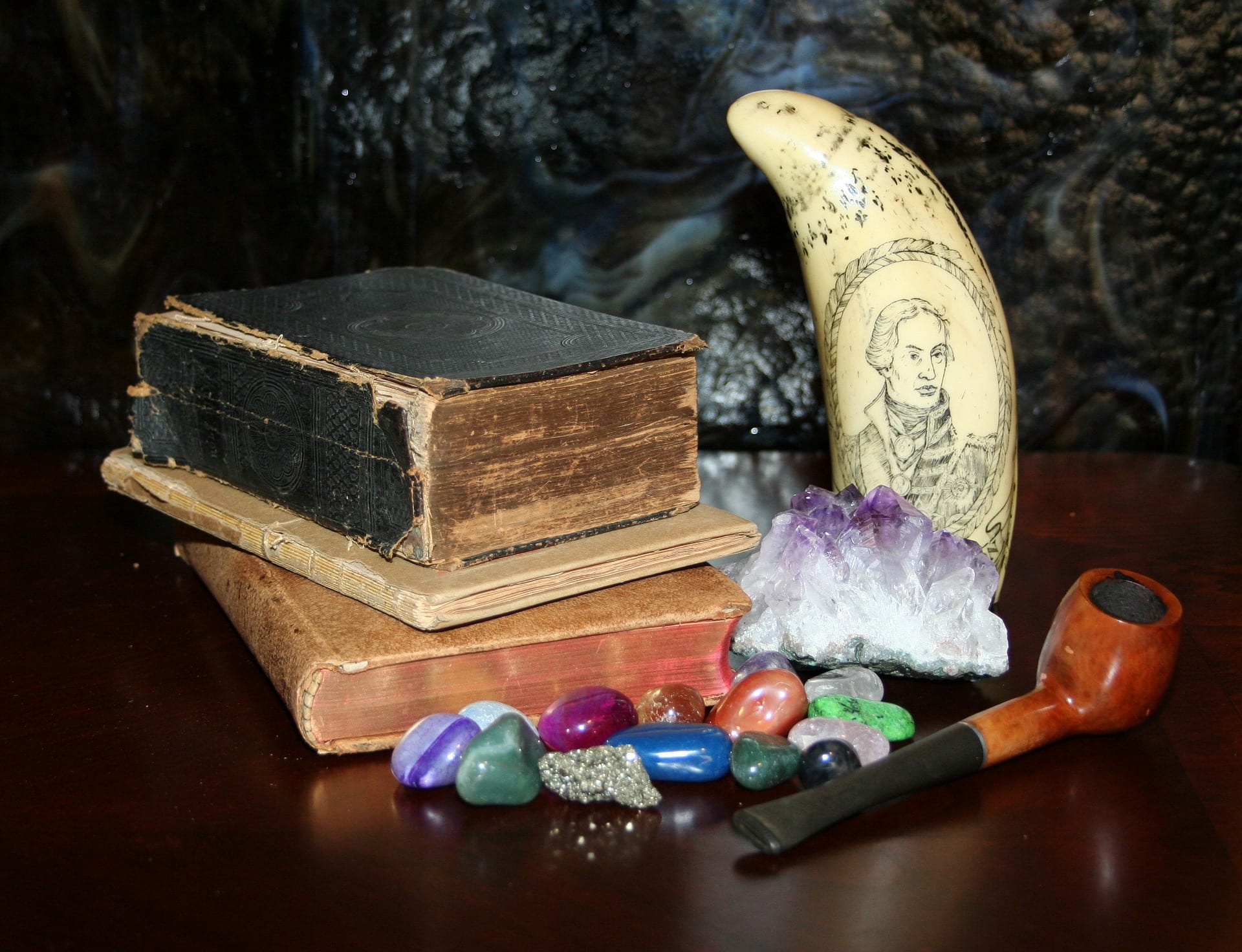

“Hard byproducts” of whaling were flotsam and jetsam of the fishery – parts of the whale that had little or no commercial value and thus could be given over to the sailors for their own pleasurable diversions. Sperm whale teeth could be polished to a high gloss, then engraved with pictures to which lampblack and colored pigments could be applied. Or they could be carved in relief or in full round, to produce sculptural forms, human and animal figures, finials, handles, tools, inlay, and all manner of ornaments for wooden boxes, canes, and other objects.

Likewise, walrus ivory was used. The walrus hunt had been associated with whaling since medieval times, and even where the whalers did not take walrus themselves (as was typically the case in the 19th century); tusks were obtained by barter with Northern peoples in Canada, Siberia, and Alaska, and were often utilized to scrimshaw. Virtually anything that could be made of whale ivory could also be crafted from walrus ivory.

The characteristics of whale and walrus ivory are similar. The advantages of sperm whale teeth are (in especially fine specimens) its milky smoothness, homogeneity of texture, breadth, and rich color. However, a length of 20 cm (or 8 inches) is uncommonly large for a sperm whale tooth; 28 cm (11 inches) is just about the record. Walrus tusks, on the other hand, frequently range up to 70 cm (about 27 inches) or longer: they not only provide a larger surface for pictorial engraving, but can be cut and sliced and combined into larger objects or larger ornaments, including the slats for swifts (yarn-winders), shafts and handles for pie crimpers, even the bars and slats for elaborate birdcages.

Baleen is the keratin plates in the mouths of the mysticete or so-called baleen whales, which includes all of the great whale species except sperm whales. Biologically, these keratin plates are larger manifestations of the same material as human fingernails, animal hoofs, and bovine horn. As applied to scrimshaw, baleen tends to be sinewy, brittle, and in many ways difficult to work; it is also vulnerable to larvae parasites. But it is also reasonably pliable, which is the basis of its commercial viability for corset stays, umbrella ribs, and skirt hoops. Properly handled, it is ideally suited for corset busks (staybusks) or bent-sided round and oval ditty-boxes. A deft artisan can also incise it effectively with pictures.

Through the centuries, each of these products had commercial value from time to time, and so was only intermittently available to whalers for their own hobby work. Baleen had many commercial applications, but a baleen surplus in Holland in the 17th century eroded its commercial value, affording mariners an opportunity to obtain pieces of baleen for their own use. Skeletal whale bone was used for architecture and artisanry by Norse and Basque whaling pioneers in medieval times; but, beginning in the 17th century, pelagic whalers – who were primarily concerned with oil and secondarily with baleen – discarded the bones as worthless deadweight. So eventually bone, too, came into the hands of whaleman-artists.

Whalemen often used the basic materials that define scrimshaw – sperm whale ivory, walrus ivory, baleen, and skeletal bone – in combination with other “found” materials, typically bits and pieces of wood, metal, sea shells, tortoise shell, and cloth. Latin American coins, in wide circulation in the Pacific, could be fashioned into finials and fixtures. The characteristic basic black pigment was lampblack, a suspension of carbon in oil, the product of combustion, easily obtained from the shipboard tryworks (oil cookery) or from ubiquitous oil lamps. (The notion that whalemen used tobacco juice as a pigment for scrimshaw is purely fanciful: it isn’t black, it doesn’t work, and not even a single example has been documented.) Colored pigments for polychrome (multi-colored) works included verdigris (a tenacious green deposit naturally forming on copper and brass), various homemade fruit and vegetable dyes, and commercially-produced india or china ink.

Scrimshaw Precursors

Whale ivory, bone, and baleen precursors to whalemen’s scrimshaw appeared almost from the beginning of medieval European whaling: domestic implements carved out of skeletal bone by Vikings in Norway, game pieces and chessmen made at Paris, Cologne, and elsewhere, and an impressive inventory of 11th- and 12-century votive carvings produced in English and Danish monasteries. Walrus tusks from Norway became a cheaper substitute for elephant ivory (which was imported to Europe from Africa by Venetian and Genoese merchants), and found its way into the hands of artisans in Central Europe, England, Turkey, Russia, and Spain. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Dutch and German whaling captains occasionally used baleen to make oval boxes, mangles (for folding cloth), and votive objects commemorating a family event or a successful hunt.

The Advent of Whalemen’s Scrimshaw

The meteoric rise of whaling was not until after the Napoleonic Wars, resulting in longer voyages, larger crews, and over-manned ships, creating an atmosphere for scrimshaw to flourish on a large scale. A few bone swifts, straightedges, and hand-tools survive from the 18th century; but the earliest known works of engraved pictorial scrimshaw date from circa 1817-21. Contrary to popular belief in many quarters, which ascribes the origin of pictorial scrimshaw to American hands, the first practitioners to adorn sperm whale teeth were British South Sea whalers, a few of whose pioneering works survive in the Museum collection. The first piece to bear a date is elaborately but anonymously inscribed from the whaleship Adam of London, date 1817. The first known American scrimshaw artist, and one of the best, was Edward Burdett (1805-1833), who began scrimshandering circa 1824. The first American piece to bear a date is a recently-discovered tooth engraved by Edward Burdett aboard the ship Origon of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, in 1827. The most famous early scrimshaw artist is Burdett’s fellow-Nantucketer Frederick Myrick (1808-1862), who produced 36 or more so-called “Susan’s Teeth” aboard the Nantucket ship Susan during 1828-29: he was the first ever to sign and date some of his work. These pioneers were the vanguard of a tremendously productive generation of American, British, and Australian scrimshaw artists who followed in the 1830s and ’40s, the Golden Age of scrimshaw.

Pictorial Scrimshaw

From the orthodox ship-portraits and whaling scenes pioneered in the 1820s, the pictorial repertoire expanded dramatically in the 1830s to include virtually every kind of image and theme. Sedate female figures and family groupings were persistent favorites. Patriotic subjects, naval scenes, symbolic figures like Britannia, Columbia, and Hope, and portraits of Great Men and Women – George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, Napoleon, Josephine Bonaparte, and Jenny Lind – abounded. The scrimshanders’ eye took in all subjects and themes, Biblical, mythological, and theatrical, zoölogical and botanical, urban, rural, religious, and ecclesiastical, domestic, foreign, exotic, and banal.

Diversity of Scrimshaw

It is the remarkable diversity and intricate ingenuity of shipboard scrimshaw that drew the comments of contemporaneous observers. Reverend Henry Cheever remarked that “skimshander” is a term for “the ways in which whalemen busy themselves when making passages, and in the intervals of taking whales, in working up sperm whales’ jaws and teeth and right whale bone into boxes, swifts, reels, canes, whips, folders, stamps, and all sorts of things, according to their ingenuity” (The Whale and His Captors, 1850). Herman Melville, a veteran whaleman, if not actually a scrimshaw artist himself, describes the genre as “lively sketches of whales and whaling-scenes, graven by the fishermen themselves on Sperm Whale-teeth, or ladies’ busks wrought out of the Right Whale-bone, and other like skrimshander articles, as the whalemen call the numerous little ingenious contrivances they elaborately carve out of the rough material in the hours of ocean leisure” (Moby Dick, 1851). There were indeed many types, produced primarily as mementos and souvenirs for the whalemen themselves, and especially as gifts for loved ones at home.

The swift (an elaborate yarn-winder), a distinctively American form, was an early and persistent manifestation. Pie crimpers and kitchen implements proliferated. Corset busks (staybusks) and canes (walking sticks) were epidemic: whaleman John Martin, homeward-bound with a full catch in the Lucy Ann of Wilmington, Delaware, in 1844, wrote whimsically in his journal, “There are enough canes in this ship to supply all the old men in Wilmington.” Ditty boxes, workboxes, and tabletop chests could be extremely simple or highly ornate, made entirely of baleen or bone, or a combination of materials and inlays, sometimes surmounted with a human or animal figure carved in full round. Aromatic boxes of precious Polynesian sandalwood, often exquisitely inlaid with ivory, abalone, and silver, were constructed by many painstaking seamen. Among the most elaborate creations were “architectural” or “architectonic” forms: pocket watch stands, usually shaped like miniature “grandfather” clocks (tall clocks), a nighttime resting place for dad’s gold timepiece. Sewing boxes, typically built of wood or bone, often lavishly fitted with drawers, spools for thread, pincushions, and other accessories, were characteristically ornately decorated with inlay, finials, fobs, and fixtures of marine ivory, sea shell, tortoise shell, and silver. A skeletal-bone and or wood-and-bone birdcage could consume countless months of work at sea. Banjos and violins with ivory and bone fittings were also in the inventory of the musically inclined and manually skilled.

In fact, many whalemen were quite skilled – ship’s carpenters and coopers perhaps especially so. Having been trained in the trades, their dexterity and technical competence would have been substantially better honed than average; certainly their per capita scrimshaw productivity was disproportionately high. Nor was scrimshandering limited to the whalers themselves. Wives and children, who sometimes accompanied whaling captains to sea, also produced scrimshaw in significant numbers. Some of the women – like Sallie Smith, wife of Captain Frederick Howland Smith of Dartmouth, Massachusetts – produced work to as high a standard as their male counterparts.

The defining characteristic of scrimshaw is the occupational context of process, materials, and personnel. It’s aesthetic, iconographical, and technical characteristics, exhibiting trends and tendencies that mostly followed fashion ashore, place it foursquare within the decorative mainstream. But its vivacious florescence within a single, sequestered occupational group render it unique, able to impart insights into the life and times of sea labor in the Age of Sail. The scrimshaw itself was produced in large measure with the artist’s mind fixed on the people back home, not only as the intended recipients of scrimshaw gifts, but also as the beneficiaries of his newly-acquired sailors’ vision of the wide world. The genre, born of the sea, constantly looks homeward to shore.

Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick: the Greatest American Whaling Story

Herman Melville (1819-1891)

On December 30, 1840, at the age of 21 years, Herman Melville signed the shipping articles for a whaling voyage to the Pacific Ocean aboard the ship Acushnet of Fairhaven, MA, Valentine Pease, master.

The vessel set sail down the Acushnet River estuary on January 3, 1841, past the great wharves of New Bedford, the then whaling capitol of the world, and out into the North Atlantic. This author of genius was being carried off on the voyage that would inspire one of the greatest works of literature in the American language.

He endured eighteen months at sea. He had little formal education but a background rich in adventure. As the character Ishmael says in Moby-Dick, “... a whale ship was my Yale College and my Harvard.” In writing his novel, Melville drew primarily on what he had learned at sea. While on the Acushnet, he met Owen Chase during a gam (exchange of visits between whaleships). Chase gave him a written account of his father’s experiences on the Ship Essex, which was sunk by a whale. “The reading of this wondrous story on the landless sea, and so close to the very latitude of the shipwreck, had a surprising effect upon me,” Melville later wrote.

The Book Itself: Moby-Dick

was first published in London under a different title before its publication in New York. The following bibliographic descriptions of the first editions are quoted directly from G. Thomas Tanselle, A Checklist of Editions of Moby-Dick, 1851-1976 (Evanston and Chicago, 1976), p. 8.

1. The Whale. London: Richard Bentley, 1851 3 vols. (viii, 312; iv, 303; iv, 328 pp.) Published October 18, 1851; at a guinea and a half, in an edition of 500 copies. Bentley, the foremost publisher of the “three-decker,” gave The Whale an unusually elaborate physical dress: deep-blue cloth covers, and white spines decorated with gold whales (unfortunately they were right whales, not sperm whales like Moby Dick). It is difficult to understand why he gave such lavish treatment to a work which was so different from typical three-decker fiction and for which he expected small sales. Probably about a third of the edition was bound this way, for Bentley later covered some sets with ordinary brown and purple cloth and still had sheets available in 1853 for his one-volume issue. All copies of the Bentley edition are thus from the same impression, but they can occur (1) in three volumes with blue and white cloth and gold-stamped whales on the spines, (2) in three volumes with brown or purple cloth and no whales on the spines, and (3) in one volume with red cloth and cancel title pages dated 1853.

2. Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1851. xxiii, 635 pages. Published probably on November 14, 1851, at $1.50, in an impression of 2, 915 copies. The Harpers presented the work as a single bulky volume, covered with various colors of cloth (red, blue, green, purple, brown or black) and bearing a blind-stamped life preserver device on the front and back covers. Although the Harper volumes were much less attractive than Bentley’s three-deckers, it is possible that Melville preferred them, for he believed that “books should be appropriatly apparelled” (as he said in his review of Cooper’s The Red Rover), and at least the reviewer of Moby-Dick for the New Bedford Daily Mercury thought that the Harper volumes were “in some respects ‘very like a whale’ even in outward appearance.” Some first impression sheets were later (about mid-1852) cased in cloth that was blind-stamped with an arabesque pattern on the front and back. A second printing (250 copies) appeared in 1855, a third (253 copies) in 1863, and a fourth (277 copies) in 1871, each with a dated title page.

All told Tanselle lists 115 editions of Moby-Dick.

American Whaling Literature

Before the publication of Moby-Dick, the subject of whaling had a limited but significant representation in American literature. The most famous early American accounts had more to do with sensations in the whale fishery such as Owen Chase Narrative of the most extraordinary and distressing shipwreck of the whale-ship Essex of Nantucket; which was attacked and finally destroyed by a large spermaceti-whale, in the Pacific Ocean… (New York 1821) and William Comstock The life of Samuel Comstock, the bloody mutineer (Boston, 1845) outlining the infamous mutiny on the ship Globe of Nantucket in 1824. Other such titles include William Lay and Cyrus Hussey’s account of the Globe mutiny, A Narrative of the mutiny on board the ship Globe, of Nantucket, in the Pacific Ocean, Jan. 1824 (New London, 1828) and Horace Holden, Narrative of the shipwreck, captivity, and sufferings of Horace Holden and Benj. H. Nute; who were cast away in the American ship Mentor, on the Pelew Islands, in the year 1832 (Boston, 1836). Previous to Moby-Dick there were three major American non-fiction works relating to the whale fishery. They were Francis Allyn Olmsted Incidents of a whaling voyage… (New York, 1841); J. Ross Browne Etchings of a whaling cruise…(New York, 1846) and the Reverend Henry Cheever, The whale and his captors… (New York, 1849). Additionally there were Herman Melville’s two other whaling related works of fiction, Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life… (New York, 1846) and Omoo: A Narrative of Adventure in the South Seas… (New York, 1847). Although additional minor titles, such as Reuben Delano, Wanderings and Adventures of Reuben Delano, being a narrative of twelve years’ life in a whale ship (New York, Boston and Worcester, 1846) were published the above list represents the bulk of popular American writing on the subject before 1851. After 1851 a wide variety of works of fiction and non-fiction including dime novels, temperance pamphlets, reminiscences and additional primary accounts came increasingly into the public sphere.

Mocha Dick

Melville was also influenced by stories whalemen told about a ferocious white whale. Twelve years before Moby-Dick, a U.S. naval officer wrote an article, “Mocha Dick: The White Whale of the Pacific,” in which he described a great whale that was “white as wool.” When the Mocha Dick of this tale was captured, the crew found twenty harpoons in his body from previous attempts to kill him.

Captain Ahab and the Pequod

All these influences eventually inspired Melville’s tale of a mad captain and his doomed ship and crew, which was published in 1851. As the novel begins, Ishmael joins the crew of Captain Ahab, who is determined to find and kill the white sperm whale known to whalemen as Moby-Dick. Ahab had lost one of his legs in an earlier attempt to capture the great beast. In the final encounter, Captain Ahab, crew, and ship are destroyed. Only the narrator, Ishmael, survives to tell the story.

The world of the Yankee whaleman

Moby-Dick is a great, sprawling book that moves back and forth between the main story line and Melville’s digressions on whales, whalecraft, and other subjects. He vividly captures the environment of the Yankee whaler — a world of exciting chases and dangerous, violent work; years of boredom and loneliness; exotic ports, cannibal crewmen, and strange events; and, always, “the great shroud of the sea,” as Melville described it.

History’s Verdict

Moby-Dick is today considered one of the greatest of all American novels; although when it was first published the critics gave it mixed, sometimes scathing reviews.

The Moby Dick Marathon

Annually, on the first weekend after New Years Day, the New Bedford Whaling Museum sponsors a non-stop reading of Moby-Dick to mark the anniversary of Herman Melville’s departure on the Acushnet. Scores of people converge on the Museum and take turns reading, completing the novel in 25 hours.