The Works and Legacy of Albert Pinkham Ryder

Whether you are miles away from New Bedford or right here in the Whaling Museum, this webpage provides an opportunity to view the content of the exhibition at your own pace, and with the aid of tools that make it easier to see, read, and look closely.

Every artwork in the exhibition has an accompanying label posted on the gallery walls. You can read those labels below and, where we have permission from lenders, you can also view photographs of the artwork.

Use the Table of Contents to select a specific piece of artwork to learn more about it, or simply scroll down the page. Alternatively, if you are currently visiting the Museum, scan the QR code(s) throughout the exhibition with your smart phone to jump directly to a painting’s details.

Content on this page is organized based on how the curatorial team envisioned you could best experience what made Ryder’s work unique in his own time, as well as enduringly influential and relevant. More than a century after his death, his methods and masterful talent continue to impact contemporary artists. Learn more about Albert Pinkham Ryder's legacy by virtually touring this landmark exhibition, or by visiting the Whaling Museum in person.

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Flying Dutchman

COMPLETED BY 1887

OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON FIBERBOARD

Numerous 19th century authors popularized the story of a Dutch sea captain who blasphemes by swearing on a relic of the true cross that no storm could defeat him, even if he sailed until Judgment Day. The Devil accepts the challenge, requiring the Dutchman’s son to pursue the phantom ship for years, bearing the relic that will redeem his father. The fall from grace and redemption became central subjects for Ryder’s major canvases. Everything in this painting – centrifugal rhythms, mingled colors, urgent paint handling, narrative of desperation – ascends to a higher key, reflecting Ryder’s greater mastery and the growing intensity of his emotions.

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly

Albert Pinkham Ryder's Easel

c. LATE 19TH OR EARLY 20TH CENTURY

WOOD

Sometime before his death in 1917, Ryder gave his easel to his sole student in New York City, Louise Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick, in turn, gave it to her close friend, Flora Evergood, for the use of her son, Philip. Evergood, a Social Realist painter, was strongly influenced by Ryder. Evergood’s widow gave the easel to her caregiver, who gave it to Evergood’s biographer, Dr. Kendall Taylor. From there, it made its way to William Vareika Fine Arts in Newport, and finally, to the New Bedford Whaling Museum, where it resides alongside Ryder’s Landscape. The endpapers of the catalogue accompanying this exhibition are detailed shots of the paint splatter on this easel.

New Bedford Whaling Museum purchase, 2005.7. Purchased with gifts from William Vareika and the Amy Janes Bare Charitable Trust, Bernard Taradash, Trustee.

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Weir’s Orchard

COMPLETED 1885 - 1890

OIL ON CANVAS

Painter J. Alden Weir was among Ryder’s closest friends from their student days in New York throughout their careers. Weir married in 1882 and moved to a large farm near Ridgefield, Connecticut, which became a rural retreat for Ryder, as well as Hassam, Sargent, and Twachtman. At the farm, Ryder could escape the city and renew his deep love of nature.

After recuperating there from an illness in 1897, Ryder wrote to Weir, “I have never seen the beauty of spring before.…That eloquent little fruit tree that we looked at together, like a spirit among the more earthly colors, is already losing its fairy blossoms, showing the lesson of life; how alert we must be if we would have its gifts and values.” Weir’s Orchard may commemorate this experience.

Loan courtesy of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT. The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Landscape

COMPLETED BY 1870

OIL ON CANVAS

This early landscape is revolutionary in the way it almost dissolves into abstraction, with large areas of light and shadow balancing the composition of trees bordering a canal. The canvas may have been unprimed, allowing the weave to be visible in areas where thinned paint stains the fabric rather than resting on the surface. Glossy glazes add highlights in some areas. From the beginning, Ryder departed from conventional techniques to explore new ways of using pigments and media, saying he wanted to get his paint “less painty looking.” The first recorded owner of this painting was C.E.S. Wood of Portland, Oregon, who would become the artist’s most sympathetic and inspired supporter. It returned to Ryder’s hometown in 2004 when patrons of the New Bedford Whaling Museum purchased it for the collection.

New Bedford Whaling Museum purchase, 2005.3

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Near Litchfield, Connecticut

COMPLETED BY 1876

OIL ON COMPOSITION BOARD

An inscription on the back of this small landscape cites the location in Connecticut and year when it was created and adds that it was presented to Charles de Kay, who was then the art critic for the New York Times. This helpfully shows that, even at the beginning of his career, the artist cultivated useful connections and was ambitious for his art to succeed.

Ryder’s first paintings were mostly landscapes in a pastoral mood, revealing an artist who revered nature and sought to capture its inner vitality. The free brushwork and fresh colors of Near Litchfield reflect his search for an intensity of expression that he said was “vibrating with the thrill of a new creation.”

The small size of Ryder’s early paintings cannot obscure his intention to experiment with new approaches and elevate nature into a spiritual realm.

Loan courtesy of the family of Robin B. Martin

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Landscape – Woman and Child

c. 1875

OIL ON BOARD

Ryder’s several small landscapes with a woman and child were prized for exploring feeling over form, placing him clearly among the “new men” in American art. An early reviewer, William Brownell, noted the vagueness of Ryder’s figures, but cautioned him against “correcting” them, saying in doing so “we should fear for their poetic feeling, their engaging color, and their softness and tenderness, even to lose their fragmentariness would, one feels, be risky.”

Loan courtesy of a private collection

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

The Lovers’ Boat

COMPLETED BY 1881

OIL ON BOARD

Two lovers drift through a narrow channel in a sailboat, sheltering under an exotic canopy in the stern. The ghostly glow of a full moon outlines simple forms. This is likely Ryder’s first nocturne, but already he uses novel means to achieve the mystery of dark sky and watery reflections, leaving the panel unpainted in places and allowing warm tones of varnished wood to create a spectral scene. Ryder called attention to the effect in the accompanying poem, saying the boat glides “into the deeper shadows / of sky and land reflected.”

He exhibited the painting in 1881, when his youthful interest in pastoral landscapes was giving way to a fascination with romantic love as expressed in poetry and literature. His deeply personal vision was coming into focus: “…no two visions are alike, and those who reach the heights have all toiled up the steep mountain by a different route. To each has been revealed a different panorama.”

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Alastair B. Martin

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

A Country Girl

c. 1903

OIL ON CANVAS

Ryder’s increasing preoccupation with romantic love is seen in his mid-career subjects and in his personal life as well. This beguiling simple country girl looks straight at the viewer with an inviting glance, her billowing skirt echoing the sway of the trees and revealing a glimpse of slip. Of the several simple young maidens in Ryder’s oeuvre — many, like Perrette and Little Maid of Acadie inhabiting the realm of literature — this feels most immediate, like a “real-life” girl.

Ryder was shy with women, adopting an elaborate courtesy in his rare interactions with them. His mother had worn Quaker dress; he was raised with three brothers and attended a boy’s school; there is no mention of a romantic attachment before he reached forty. So Ryder’s friends were surprised one day to learn that he had found a young girl from the country wandering the streets and brought her home to live in his apartment; the friends discretely spirited her off to the police, leaving Ryder bereft and “love sick.” His clumsiness in courtship was manifested in other ways as his loneliness grew more acute; the question of his sexual orientation was never mentioned.

Loan courtesy of the Collection of the Maier Museum of Art at Randolph College, founded as Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, Lynchburg, VA

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Landscape with Sheep

c. 1870

OIL ON PANEL

Close observation of these three sheep – their standing and reclining postures and meticulously delineated faces, horns, hooves, and volumetric proportions – shows Ryder to have been an excellent draughtsman. Later legends tried to recast him as an awkward untutored naif, but the early paintings of cows, horses, and sheep belie this.

The landscape in which these sheep exist, however, lacks any detail; the animals seem almost to hover in an essence of sun-drenched sky and autumnal grasses. His aim was not to engage in narrative, but rather to seize the deeper currents of nature.

Loan courtesy of the Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1948.3

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Pastoral Study

c. 1897

OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON FIBERBOARD

Pastoral Study is Ryder’s final revisiting of the pastoral landscape that began his career, but now he masterfully elevates the subject to a symbolic level. Lengthening shadows establish an elegiac mood, while two ancient trees, with trunks intertwined like lovers, evoke the passage of years. It is tempting to see Ovid’s story of Baucis and Philemon in this landscape, where an aged couple is turned into an intertwined oak and linden at their deaths. Though there is no record of this meaning, the work is unusually large, a size Ryder usually reserved for biblical or literary subjects.

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

The Shepherdess

EARLY 1880s

GILDED WOOD

The subject of an innocent young shepherdess, whose virtue is emblematic of her closeness to nature, was a popular theme in Ryder’s day. By adding antique panpipes and Elizabethan costuming, however, Ryder elevates this traditional scene to the realm of poetry, where swaying trees create a sacred bower and sheep attend to the song.

The glow of this small wood panel is remarkable, owing to Ryder’s use of gold leaf below the thin paint glazes. He was on a search for a more translucent, gem-like color effect, believing light would penetrate the glazes and reflect off the underlying gold leaf. He once remarked to a friend that all that was left to a modern master was to “improve the medium.”

Loan courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum, Frederick Loeser Fund 14.553

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Spring

COMPLETED ABOUT 1879

OIL ON CANVAS

This painting is key to understanding Ryder’s early success as a modern painter of feeling over form. It was reproduced as an engraving in an 1880 article called “The Younger Painters of America,” after being exhibited in New York the previous year. Comparing the published engraving to the appearance of the work today, we see that nothing has changed, giving us one securely dated early work against which to judge other somewhat similar paintings whose histories are clouded by alterations, deteriorated condition, or insecure dating and attribution. Spring, then, anchors the early pastoral stage of Ryder’s career.

The image of a woman holding a child and standing near a tree, without narrative or incident, invites a metaphorical reading as emblem of springtime. This leads to an understanding of the delicately leafing trees and lipid golden light suffusing the atmosphere and reflecting off water as the true subject of the work.

Ryder achieved his evanescent coloration by using many thin tinted glazes. The paint film along the left edge of the artwork is noticeably thicker than elsewhere, suggesting that the work was stored on its side before the glazes and varnishes had dried.

Toledo Museum of Art, Gift of Florence Scott Libbey, 1923.3134

Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847 – 1917)

By the Tomb of the Prophet

AFTER 1882

OIL ON PANEL

Ryder sampled several different genres and subjects early in his career, painting decorative furniture panels and leather screens, as well as a mirror frame. This is one of a handful of orientalist subjects he created when these “exotic” subjects captured the fancy of the art world, inspired by Delacroix, Gerome, and Tiffany.

A minaret and a pyramid loom over the long wall of a Middle Eastern “old city,” but Ryder seems equally interested in the cluster of horses waiting in the foreground. Once again, he features a white horse, the favorite protagonist of his early paintings.

The size and format of this small work suggest it is painted on a wooden cigar box lid, which Ryder frequently chose as a support.

5 13/16 × 11 7/16 inches, frame: 15 1/2 × 20 1/2 × 3 3/4 inches

Loan courtesy of the Delaware Art Museum, Acquired through the George I. Speer Bequest, 1968

Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847 – 1917)

An Oriental Camp

c. 1875

OIL ON CANVAS

For decades, aspiring American artists traveled to Italy to draw inspiration from the classical monuments of antiquity. In the 1860s and ‘70s, modern, forward-leaning artists turned away from the rationality of the Greco-Roman tradition, favoring instead the richer colors and more sensual art of North Africa and the Middle East. Although Ryder did not travel to those countries until the early 1880s, he was attracted even earlier to the “exotic” scenes of Arab market places and nomadic traders that were featured in many exhibitions.

An Oriental Camp summarizes this shift in Ryder’s art, marking him as one of the “modern men.” X-rays reveal that there was originally an imposing classical façade painted at the right of the canvas, now completely overpainted and replaced with mysterious Arab tents dominating the scene. Ryder included a camel and several horses in the scene, with a trader’s head and arm shown just behind the white horse. The thick paint film has deteriorated over the years, but we can still discern the touches of color that dazzled contemporary critics – see the glowing red saddle on the white horse or the rich chestnut coloration of the horse at right.

Loan courtesy of the Mead Art Museum of Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts, Gift of George D. Pratt (Class of 1893)

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

The Mosque in the Desert

1883

OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON BOARD

This canvas shows four Arab horsemen with lances approaching an enormous domed mosque encircled by walls. As often before, Ryder featured a white horse in the starring role; all have long flowing tails. The painting’s tiny size and thin paint film, which reveal the strong twill pattern of the support, may mark it as a compositional study for another work. Still, the spirited horsemen are closely observed, and elements such as the shadow under each figure and the horses’ white hooves and saddles reveal Ryder’s careful detailing.

Loan courtesy of the Lyman Allyn Art Museum, New London, Connecticut. Bequest of Miss Alice S. Bishop, cousin of the artist

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Dancing Dryads

COMPLETED By 1879

OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON FIBERBOARD

Ryder loved poetry and music as well as art, and he frequently included the muses in his mature artworks. For this small “lyric of dawn,” he penned a couplet that was inscribed on the frame: “In the morning, ashen-hued, / Came nymphs dancing through the wood.” These whirling nymphs with long hair flying, accompanied by a seated muse, show Ryder moving beyond naturalistic subjects into the realm of the imagination. Elite collectors responded well; this small panel was first owned by New York Times art critic Charles de Kay, and then by Stanford White, an architect and leader of the “American Renaissance.”

Over time, the figures faded and became hard to distinguish from the landscape, so a restorer outlined them for clearer definition.

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid

COMPLETED By 1906 or 1907

OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON FIBERBOARD

The subject of an African king who was bewitched by the beauty of a poor beggar maid began as an Elizabethan ballad and became a popular theme for Shakespeare, Tennyson, and several late Victorian artists. Although Ryder was regarded as a recluse in later life, he was widely traveled, with four trips to Europe and visits to many key museums and collections, and he was well acquainted with modern literature.

Ryder often chose subjects that elevated the nobility of true love over material wealth and temporal power, and he gravitated to subjects that united lovers across ethnic as well as class divides.

Technical studies show that Ryder liked to start an image on a surface that had been previously used. This canvas began with a painting of a large horse oriented as a horizontal image; an early stage of this literary subject included a small cow near the beggar maid, making her a shepherdess. Working and reworking the image, he reduced it to essential features — a mounted nobleman, a graceful maid, each framed against a high hill — and finally arrived at the poses and spatial tensions that evoke the exact moment of enchantment.

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

The Lorelei

c. 1896 – 1917

OIL ON CANVAS

A singing woman held huge romantic appeal for Ryder, who once is said to have impulsively proposed marriage to a woman singing in a nearby apartment. But the charming singer of several early paintings was transformed into an evil seductress who lured sailors to their deaths in The Lorelei (from a poem by Heinrich Heine). Ryder’s deepening solitude and despair reflects his disappointment in love.

Combining subject, meaning, mood, composition, rhythmic forces, and brushwork into a unified image that expresses an existential truth was never easy for Ryder. After 1897, deteriorating health increasingly compromised his efforts. Around that time, he announced that he had finished The Lorelei, but in fact he continued to rework it until his death in 1917, “fretting and stewing” as he repositioned the “witching maiden” on the jagged rock overlooking sailors below. After his death, the murky paint surface was further disturbed by a restorer.

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Tulip Tree Foundation

Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847 – 1917)

The Grazing Horse

MID-1870s

OIL ON CANVAS

Several of Ryder’s early paintings of farm animals were acquired by his dealer, Daniel Cottier, and in 1914 six of these were purchased from Cottier’s widow by the Brooklyn Museum – the first Ryder paintings to enter any museum collection. The museum invited the artist to sign each work on the back of the stretcher, arming authenticity as Ryder forgeries were beginning to emerge. Other collectors followed suit, asking Ryder to endorse their paintings, which he did. In at least a couple of instances, he signed works that are now known forgeries or even tinted photographs, perhaps from a reluctance to embarrass the owners, or because his advancing illness and impaired eyesight left him confused about their authorship. Whether a painting bears Ryder’s signature or not is of no use in determining authenticity.

Loan courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum, Augustus Graham School of Design Fund 14.554

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Pegasus Departing

BY 1901

OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON FIBERBOARD

The poet on Pegasus is leaving the land of the muses after seeking inspiration for his art. This work has a disturbed surface that betrays its contentious history. Ryder was a notoriously slow producer, laboring sometimes for years on a single image until it was “felt as true.” When collector John Gellatly pestered Ryder to complete this painting for his new salon, the angered artist scarred the painting with a metal comb rather than give it up; the resulting structural problems are revealed in the x-ray of the image. Ryder eventually repainted the image, blurring many forms; at some point, the damaged canvas was transferred to panel.

The uncertain foreshortening of Pegasus suggests Ryder may have been looking at an illusionistic ceiling painting, perhaps Delacroix’s horse-drawn chariot of Apollo on the ceiling of the Louvre.

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly

Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847 – 1917)

Pegasus

OIL ON WOOD

In his early career, Ryder preferred horses to any other subject, painting them grazing or standing in stables. He included horses in several subjects even when there was no narrative reason for them. His ambition expanded after he toured European museums. Soon Ryder’s horse took wing and was transformed into Pegasus, the mythical steed who carried the muses to Mount Helicon, the source of poetic inspiration. This tiny but ecstatic panel features the winged Pegasus with two muses, a small cherub, a radiating sun, and a steep cli. It announces a turning point in his art, signaling his immersion in the realm of poetry and myth; his early fascination with nature gives way to the world of the imagination.

Loan courtesy of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institutions, Washington, DC, Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1966

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Lord Ullin’s Daughter

BEFORE 1907

OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON FIBERBOARD

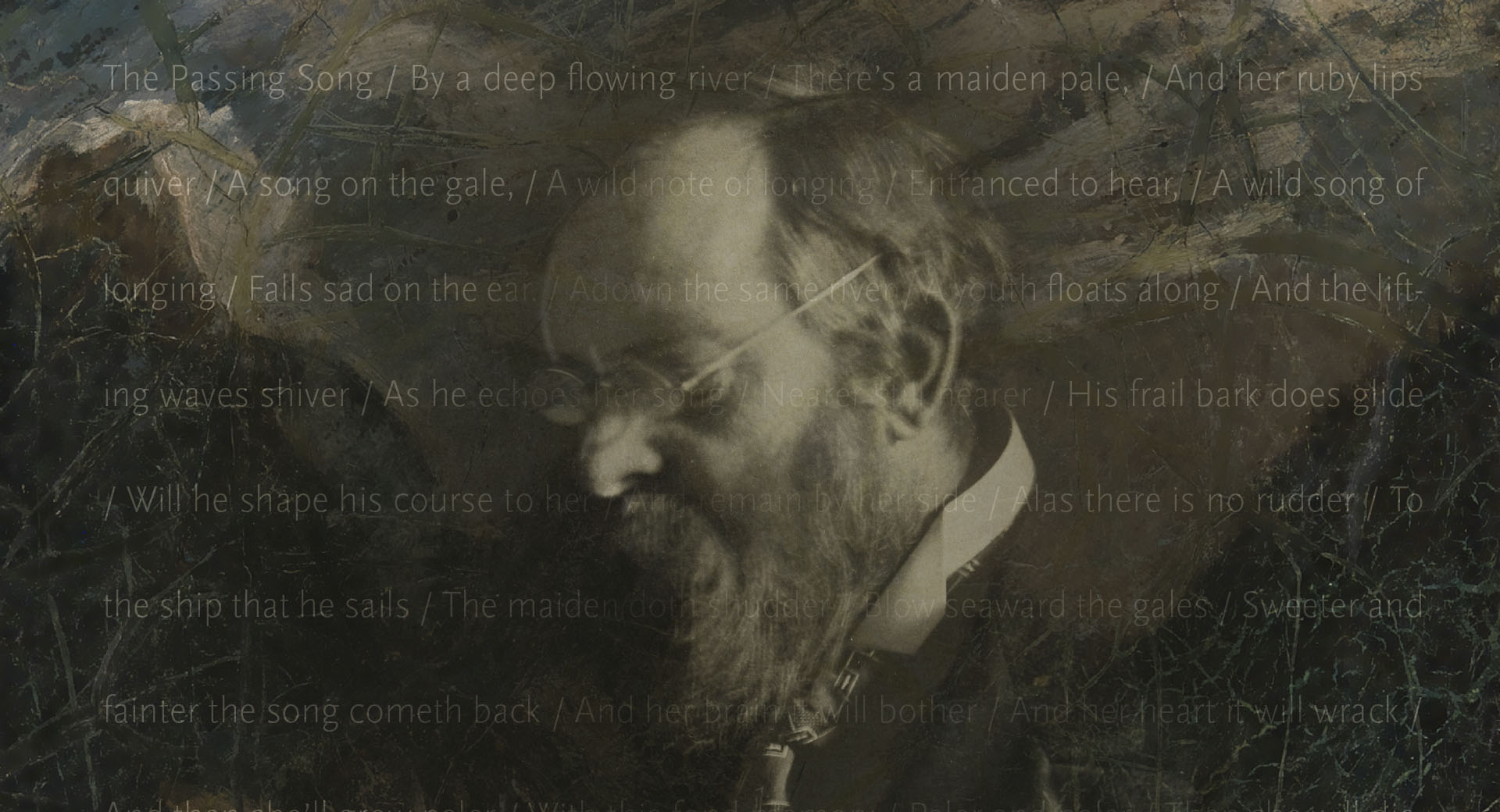

A poem by Thomas Campbell tells of two lovers attempting a desperate escape from the lady’s wrathful father, but they are overpowered by storm-whipped waves and drowned. With this image, Ryder’s early hopeful paintings of lovers takes a tragic turn, as his own hopes for love withered over the years. In one of Ryder’s poems, he wrote of “a wild note of longing.”

Massive swells rise in the foreground, gathering force and thrusting upward, until a giant wave fatally assaults the boat. As if in response, enormous rocky cliffs jut up at an opposing angle and carry the energy into the sky, where dark clouds, haloed by light from an obscured moon, release the tension at the top of the frame. Ryder’s brushwork is a tour-de-force of pigments mixed wet-on-wet that variously create water, rock, and air, leading a New York Times critic to praise his “massive and simple” forms that are all of “one texture … one rich and precious material.”

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Jonah

c. 1885 – 1895

OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON FIBERBOARD

Ryder worked for a decade on his greatest masterpiece, finally achieving the ultimate vision of abandonment and redemption that were his most profound subjects. The Old Testament book tells how Jonah defied God’s command and experienced His vengeful wrath; rebuked and repentant, Jonah surrendered entirely to God’s will and was redeemed.

This large painting unites inspired compositional rhythms and wholly reinvented paint-handling to create a new form of dramatic expression. Ryder knew his approach was revolutionary. “Have you ever seen an inch worm crawl up a leaf or a twig, and then clinging to the very end, revolve in the air, feeling for something to reach something? That’s like me. I am trying to find something out there beyond the place on which I have a footing.”

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Homeward Bound

c. 1893 – 1894

OIL ON CANVAS ON WOOD

Washington businessman Duncan Phillips lost his beloved older brother during the 1918 flu pandemic. He wrote, “Sorrow all but overwhelmed me. Then I turned to my love of painting for the will to live.” He began collecting and, in 1921, opened the first modern art museum in America as a memorial to his brother.

Phillips was deeply affected by Ryder’s paintings, including this blissful scene of a boat in full sail cruising toward an open horizon under a translucent sky. Ryder painted it while returning from a trip to Europe, which he undertook for the pleasure of an ocean voyage with his friend, Captain John Robinson.

Phillips wrote, “All of Ryder is in the small marine entitled Homeward Bound. … That little boat at the center of the composition, as each of us is at the center of his particular universe, symbolized the soul’s adventure as it traverses the vast, uncharted solitude, travelling toward the unknown.”

Loan courtesy of the Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. Acquired 1921

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

With Sloping Mast and Dipping Prow

c. 1880 – 1885

OIL ON CANVAS MOUNTED ON FIBERBOARD

Ryder finds his mature voice in this small seascape, where the rocking motion of a sailboat launches a compositional rhythm that continues through the sky, orbiting around the full moon. A large wave once rose at left and lifted the stern, contributing to the rhythm, before it was altered by a restorer. The inspired brushwork in waves and sky create a mystical mood; the gravitational pull of the moon orchestrates the energies.

In early exhibitions, this work was simply called Moonlight; later it was retitled with a line from Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” perhaps to reinforce the “sloping” and “dipping” rhythms in the work.

Loan courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly

Charles Ephraim Burchfield (1893 – 1967)

Nature’s Mystic Spiral

1916

WATERCOLOR AND GRAPHITE ON PAPER

Charles Burchfield’s ecstatic embrace of nature was at its most intense in 1916, when he made hundreds of transcendent, even hallucinatory, watercolors. Of these, Nature’s Mystic Spiral is the most magical, evoking not only Ryder’s sublime moonlit scenes but also Van Gogh’s Starry Night, where dark cypress trees stand as witness to the celestial spectacle.

Ryder’s dreamy moonlights inspired many early modernist painters to create their own visionary works. Burchfield, Dove, Hartley, O’Kee e, and others used the motif of auras rippling outward from the sun or moon; these powerful waves of energy emanating from a mystical source travel the heavens to reach us in our terrestrial reality, opening a path to a higher spiritual realm.

Loan courtesy of the Wadsworth Atheneum, Bequest of Edward Gorey

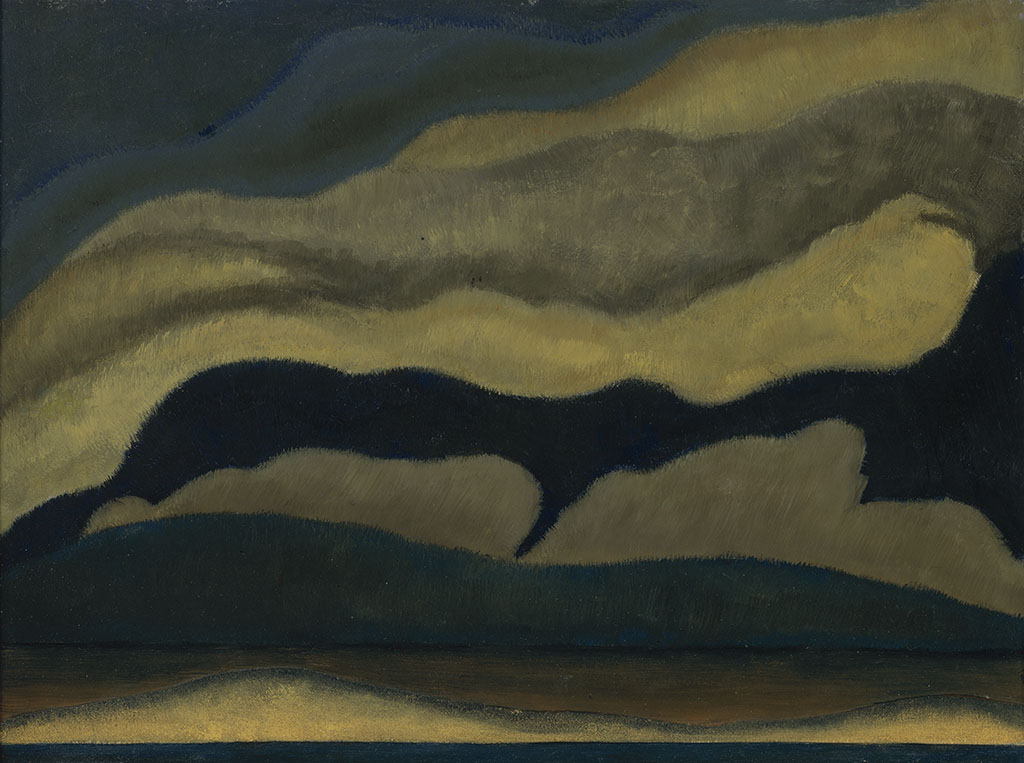

Thomas Hart Benton (1889 – 1975)

The Cliffs

1921

OIL ON CANVAS

The rhythms of the dramatic landscapes on the west end of Benton’s beloved Martha’s Vineyard echo in this dramatic and vibrant view of the seaside cliffs of Chilmark and Aquinnah. The hard edges and contrasts are fixed in a tumult of somehow conflicting yet complimentary patterns, merging sea and land as interwoven in their influence upon one another. This evokes a comparison with Ryder’s later works that reduce elements to their most basic forms of pattern and light.

Loan courtesy of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institutions, Washington, DC, Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1966

©️ 2021 T.H. and R.P. Benton Trusts / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jackson Pollock (1912 – 1956)

T.P.’s Boat in Menemsha Pond

c. 1934

OIL ON TIN

Pollock had begun working with a heavy surface by the 1930s while studying with Thomas Hart Benton in New York. Both were using the twisting, turning, rhythmic forms of Ryder, as well as those of Baroque art. Menemsha Pond is geographically very close to Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard, and it is interesting to see these images juxtaposed, as Pollock evokes a resonance of Ryder’s more graphic and later marine paintings rather than his earlier pastoral style.

Loan courtesy of New Britain Museum of American Art, Gift of Thomas P. Benton, 1973.113

©️ 2021 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

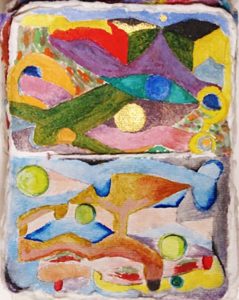

Arthur Garfield Dove (1880 – 1946)

Clouds

1927

OIL AND SANDPAPER ON ZINC

In this painting, Dove has created a world that appears to be darkening with a sense of foreboding, similar to many of Ryder’s landscapes, which evoke a “terrific austerity,” as Marsden Hartley observed. Dove incorporated non-traditional materials into his artwork, such as gauze and sand. The use of foreign materials and disrupted surfaces suggest influence from Ryder, who experimented with such things.

Loan courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of the William H. Lane Foundation

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Gay Head

UNDATED

OIL ON CANVAS

From this vantage point on the western tip of Martha’s Vineyard, Ryder could look across the waters of Menemsha Bight to see his hometown of New Bedford. The composition is essentially abstract, with interlocking diagonal layers of land and water stacked to the horizon, as if distancing the artist from his childhood. By avoiding sharp value contrasts and narrative detail, Ryder evokes a landscape of memory. Scattered farmhouses nestle comfortably in the rolling hills which are dotted with wildflowers, signaling the affection he felt for this place.

Loan courtesy of the Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. Acquired 1924

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847 – 1917)

Dead Bird

1890s

OIL ON WOOD PANEL

“Dead Bird, like Ryder’s moon paintings, became a standing challenge to later artists, something to emulate to see if they could imbue it with a similar emotional charge…The bird seems like an ancient artifact but it is part of the quotidian, a full measure of life, a cycle that Ryder’s art is filled with. It recalls an older, simpler kind of art, clear and direct, even purer, than the overly detailed images of his contemporaries.” (William C. Agee)

Image courtesy of The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1928

Marsden Hartley (1877 – 1943)

Gull

1942-43

OIL ON FABRICATED BOARD

Hartley, like Ryder, was a painter and a poet. He wrote the following in 1940, many years after the passing of his hero and friend in 1917. He did a portrait of Ryder in 1938 and produced this work shortly afterwards just before his own death. In Gull, and many other paintings, Hartley depicts a memento mori, a reminder of one’s mortality and perhaps a metaphor for the artist’s solitary existence in his old age.

Albert Ryder—Moonlightist

By Marsden Hartley

Moonlight severing his ancient mariner's

beard

and falling over the cliffs of his eyebrows

his lips fearing to touch what was no

longer available

night streaming through his listless fingers

with the texture of impassible days to come

hanging like limpid moss from his prophet

shoulders--

this beautiful man, suering from the weight

of majesty of dream

because he had been denied substance of

any other truth--dream so sumptuous--heavy

with failures of death radiant with shimmer

of new belief.

I am speaking of Albert Ryder moonlightist

as I knew him--

"I asked him to Christmas dinner," the lady

said to me, who had a long time known him

"he said he would come, we waited two hours

for him--the party eager to see him--he did

not come."

Next time she saw him--"O we were so

disappointed you did not come"--

"I was there," said Ryder, "I looked through the

window--saw the lovely lights--it was very beautiful."

Hartley, Marsden, and Gail R. Scott. The Collected Poems of Marsden Hartley, 1904-1943. Santa Rosa, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1987.

Loan courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Edith and Milton Lowenthal 1992.11.21

Nathaniel Pousette-Dart (1886 – 1965)

Untitled

c. 1952

OIL ON LINEN

Nathaniel Pousette-Dart, father of Richard Pousette-Dart, whose work is also in this exhibition, would have passed his great admiration for Ryder on to his son. Indeed, this painting is an abstraction that both points to the intersecting lines and currents of Ryder and is aligned with Pollock’s early poured paintings.

Loan courtesy of The Richard Pousette-Dart Foundation

Formerly attributed to Albert Pinkham Ryder

Nourmahal

BY 1924

OIL ON WOOD

Forgeries of Ryder’s paintings began appearing during his lifetime, and they proliferated dramatically after his death in 1917. Many people were complicit in the deception.

In 1920, the first biography of Ryder was published by Frederic Fairchild Sherman, including mention of an orientalist painting called Nourmahal, which was listed by title in an 1880 exhibition catalogue but then lost. Sherman forecasted, “When the canvas reappears, as it probably will some day, it will be found to belong with his few masterpieces.” Twelve years later, when art dealer F. Newlin Price published Ryder — a Study of Appreciation, a “newly discovered” self-portrait was the frontispiece; it showed the artist in his studio, and this painting on the wall, identified as the “lost” but now miraculously rediscovered Nourmahal.

The trap was baited. Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Bryson Burroughs petitioned the Museum’s board to purchase this unusually large “lost masterpiece,” which they did. Numerous other museums and collectors also bought clever forgeries.

In the 1930s and later, scholar Lloyd Goodrich painstakingly sorted the originals from the innumerable forgeries, much aided by the new diagnostic technique of x-radiography. Sherman had to disavow many of the “found” paintings he had authenticated, and it was revealed that at least two-thirds of the works in Price’s book were forgeries, including the frontispiece Self-Portrait and this elaborately concocted Nourmahal. The sheer extent to which the forgers went to deceive, including also a fake dealer’s stamp and letters of authentication from Ryder’s art school “friends,” indicates the esteem in which Ryder’s art was held.

Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 1932 (32.67.2)

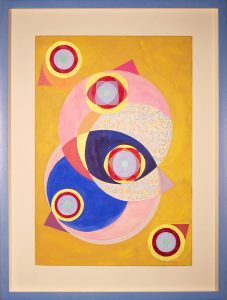

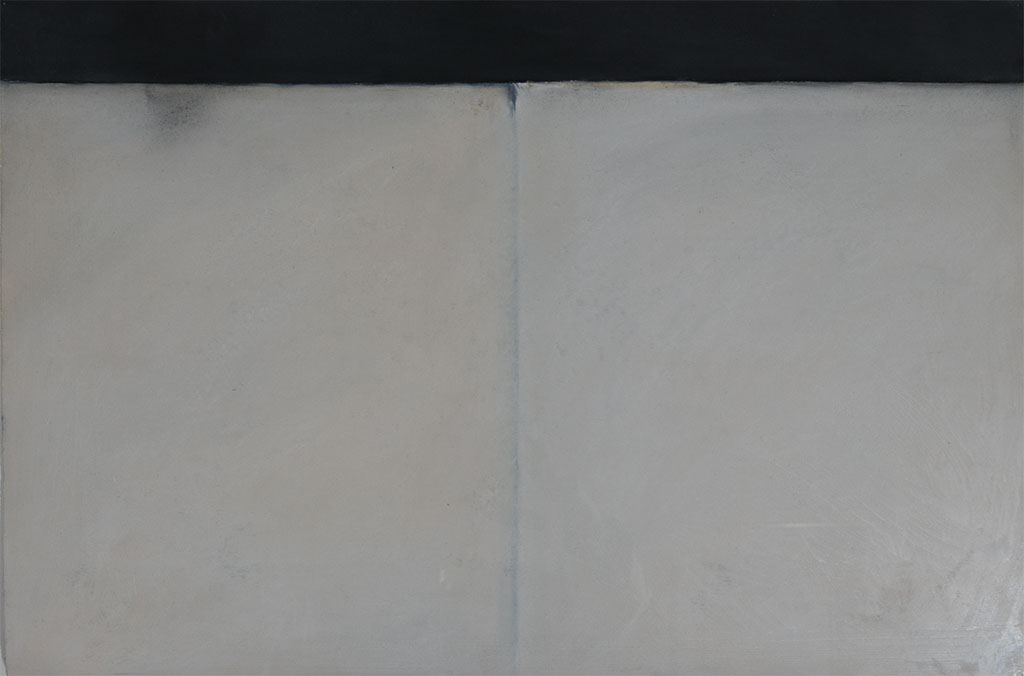

Richard Pousette-Dart (1916 – 1992)

Sombre Fusion

1943

OIL ON LINEN

Richard Pousette-Dart, an abstract expressionist, said about Ryder’s art that although it is “cracking up,” it is “more beautiful than a lot of stuff that will never crack up.” Pousette-Dart’s paintings from the 1940s, like this one, are often nocturnal scenes with nature symbols and totemic references that suggest a memory of ancient rituals and magic marks. Many have titles referring to the moon, a central feature in many of Ryder’s paintings. Pousette-Dart’s family had a house on Nantucket, and he would have felt close to the sea, which was so much a part of Ryder’s art.

Loan courtesy of The Richard Pousette-Dart Estate

Nathaniel Pousette-Dart (1886 – 1965)

Untitled

c. 1952

OIL ON LINEN

Nathaniel Pousette-Dart, father of Richard Pousette-Dart, whose work is also in this exhibition, would have passed his great admiration for Ryder on to his son. Indeed, this painting is an abstraction that both points to the intersecting lines and currents of Ryder and is aligned with Pollock’s early poured paintings.

Loan courtesy of The Richard Pousette-Dart Foundation

Ronald Bladen (1918 – 1988)

Two Yellow Arms

c. 1957 – 59

OIL ON WOOD PANEL

Ronnie Bladen was a West Coast artist, who worked with painters such as Clyfford Still in the 1940s. Bladen recalled that Ryder was an important topic of conversation and study at the time. By the late 1950s, when he created this work, Bladen was so taken with the density of Ryder’s surfaces that his own paintings became heavy physical objects, reminding one of concrete slabs.

Loan courtesy of the Colby College Museum of Art; Gift of the Alex Katz Foundation, 2013.552

©️ 2021 The Estate of Ronald Bladen, LLC / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

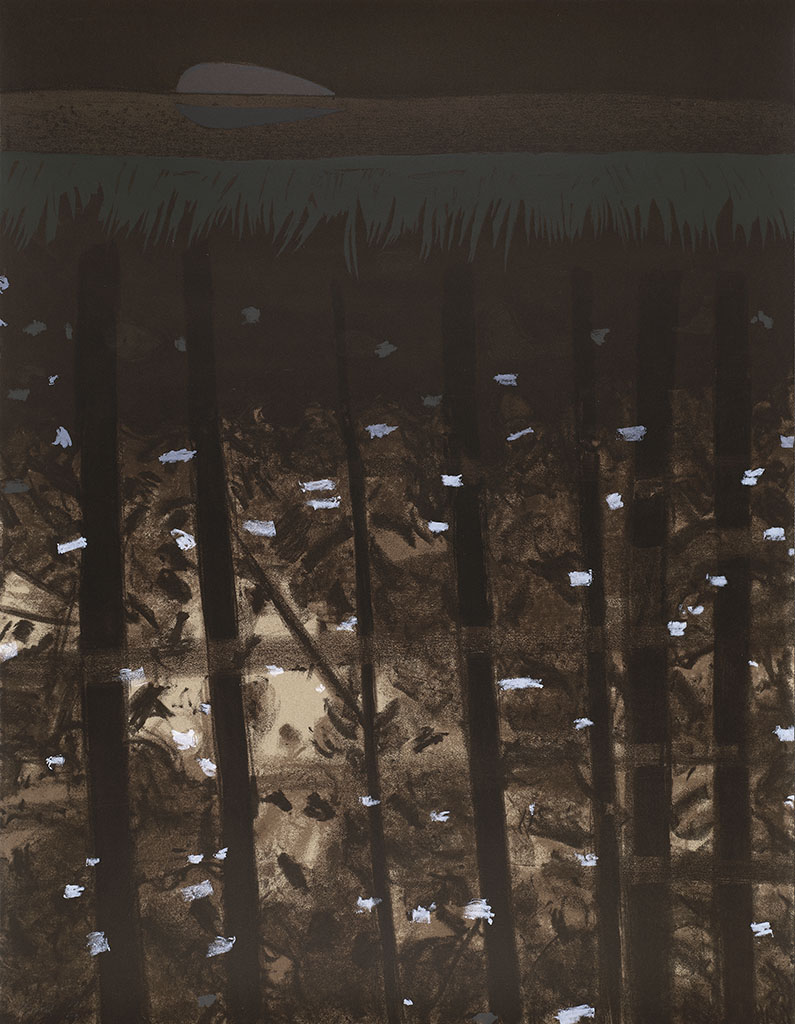

Bill Jensen

A Room of Ryders (Dedicated to Ronnie Bladen)

1986 – 88

OIL ON LINEN

Artist’s Statement:

O-I-L Paint (for Albert Ryder)

Submerged in the murk of modern life

Immersed in the murk of oil

The great mark-maker breathes forth clarity

A clarity of images and emotions

born into paint

A clarity of light and human

compassion

A clarity of poignant concentration

and compression

A murk clarity transcended

into living tissue.

The First Father, the sea, the rock, the seed,

The Witch Doctor to cure the ills of us all.

Loan courtesy of Bill Jensen

Peter Shear

Let’s Find Out

2020

OIL ON CANVAS

Artist’s Statement:

In the 1990s when I realized I was a painter the path forward appeared narrow. Painting was illegal unless it was a frowny type of painting weaponized as critique. No fun there. I kept painting and looking. Walking backwards through art history I slipped and fell on Ryder. The Racetrack was familiar from an elementary school textbook where it was paired with a Dickinson poem. Now I was confronted with everything else — pungent, intimate pictures! And each a nourishing little island, a fortunate place to get lost at a moment when, like all young artists, I was searching for the permission to be myself. Found it. Lucky me!

Loan courtesy of Peter Shear

Nicholas Whitman

Moonlit Spray on Rocks

2016

PIGMENT ON PAPER

Artist’s Statement:

I look at painting to inform my process and for revelation. Albert Pinkham Ryder’s work fills that bill. His paintings are power objects, oozing mystery an emotion.

It has become possible, with new digital capabilities, to photograph color in very low light. In photographing by moonlight one sees that there are real differences in color and atmosphere between specific nights.

Ryder was a keen observer of nature, which greatly informed his paintings. A study of Ryder’s nocturnes reveals a level of subtlety that partially explains their quiet magnetism.

As with Ryder, my work’s basis is the physical world, but more as an evocative interpretation than a literal one. Subject intersects with intangibles like mood. Symbols speak across cultures and through time.

New Bedford Whaling Museum purchase, 2018.88.2

Wolf Kahn (1927 – 2020)

Five Trees in Silhouette

2018 AND

Black Tree

2018

OIL ON CANVAS

Wolf Kahn stated that “Ryder is still one of my gods” in 2019. Through the use of built-up color and constant changes in the process of painting, Kahn arrived at the kind of light Ryder had in his paintings, light that felt both discovered and born within the painting itself. Kahn recognized the generosity of spirit that informed Ryder’s art, which included the liberal amounts of paint, the openness to experimentation, and a profound belief in art’s redemptive and restorative power.

Courtesy of the Wolf Kahn Studio, © 2021 Estate

Alex Katz (b. 1927)

Black Brook 10

1995

SCREENPRINT PRINTED FROM FOUR SCREENS IN ELEVEN COLORS

Artist’s Statement:

I think Ryder is a great painter – perhaps the best American painter ever. He certainly holds up to European painters but his style is completely American. The Phillips collection has three of his masterpieces including the one with the house by itself… I painted lots of houses after I saw that. I like the dead bird, too –the size, the scale, everything. Ryder’s works are really romantic.

Loan courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Alex Katz.

©️ 2021 Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Katherine Bradford

Four Masted Full Sail

2013

ACRYLIC ON CANVAS

Artist’s Statement:

A ghostly ship on the sea at night – this is surely a great theme of Albert Pinkham Ryder. My painter’s mind pictures the isolation of a ship on a vast dark sea and thanks to Ryder I imagine a moon all aglow high overhead.

This particular painting left out the glow of a moon but I have done plenty of sea paintings with bright white moons. In “Four Masted Full Sail” it is the light of the many stars that give the ship its luminous back light. Perhaps Ryder, who visited the harbor in the city of New York, wasn’t able to see stars because the lamp lights were too bright.

I feel close to his yearning to make something darkly mysterious yet beautiful, something as hopeful as a ship in full sail illuminated by a night sky.

Loan courtesy of Judy and Bruce

Linda Lynch (b. 1958)

Field View (Harvest)

1985

PASTEL ON COTTON PAPER

Artist’s Statement: Ryder had the horizon. He had the sea. He had brooding form and remote light. But he had these elements as a visceral understanding of nature, a primordial nature. It’s like his paintings reach that barely discernible, dimmest edge of knowledge we all recognize. He remains important to me because that is the type of knowledge that has become paramount in my own drawing process. Though he used landscape, mythology, and allegory, it feels as though his subjects served the deeper purpose of an investigation into the human predicament, our confounded situation that never truly evolves. Within a tempestuous use of paint he portrays nature, aloof to our situation, yet so irrefutably tied to us. This resonates with me as an artist looking to memory, nature, and landscape, as a catalyst for drawing.

Loan courtesy of private lender

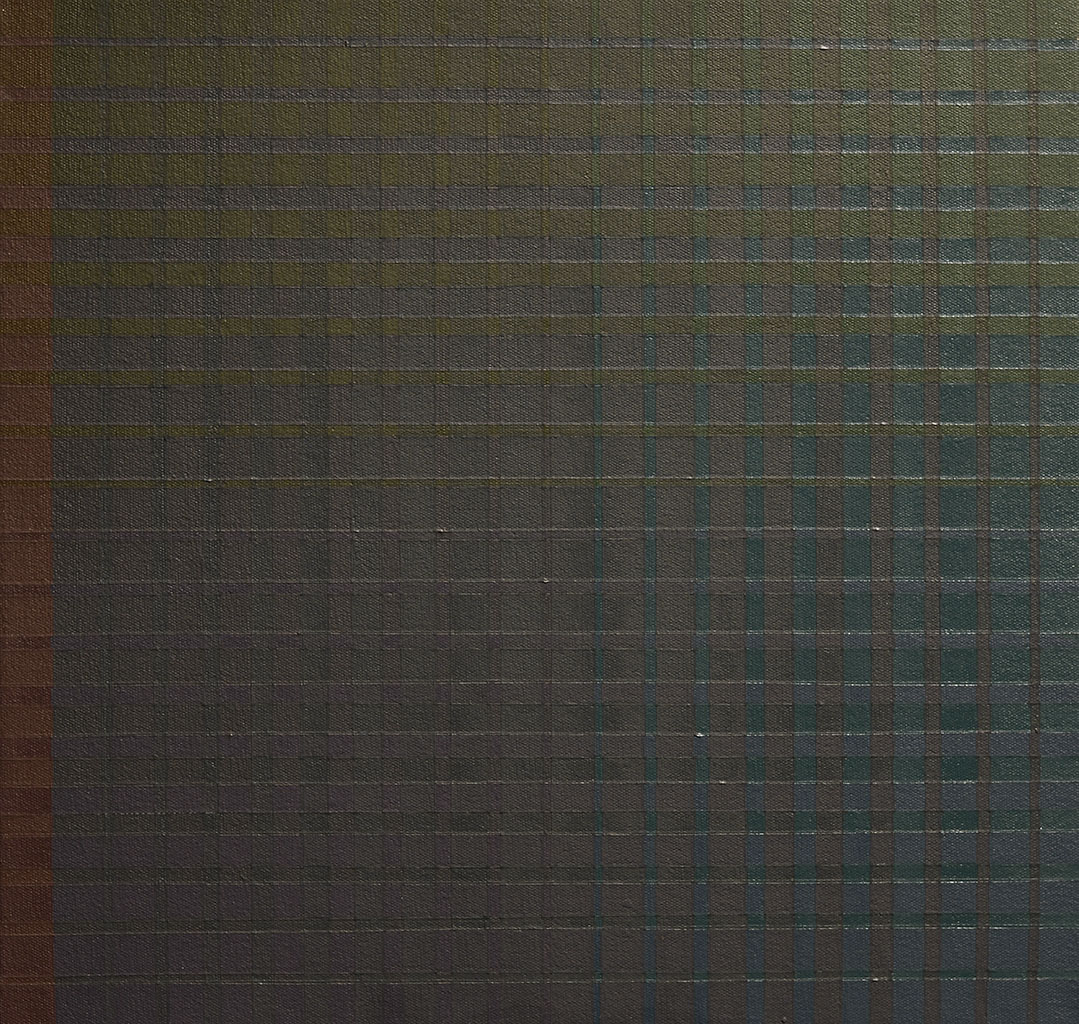

Sanford Wurmfeld (b. 1942)

II - 12 + B/1 (RO - DK + BG DK)

2017

ACRYLIC ON COTTON CANVAS

Sanford Wurmfeld creates abstract color grids, some of which extend to monumental size and scale in his 360-degree environmental cycloramas. He modulates hues of the spectrum through their full range of values from lightest to darkest, from day to night, from birth to death, the cycle of life that is seen so often in Ryder’s paintings. Wurmfeld has stated that his sense of the possibilities of sharp contrasts of binary colors was first apparent to him in Ryder’s work.

Collection of artist

Lois Dodd (b. 1927)

Night Fishing

1993

OIL ON MASONITE;

Cloud Formation

2009;

Full Moon With Aura

2017;

Moon With Halo and Clouds

2015;

Pale Moon – Streaky Clouds – Pale Sky

2010;

Up Road Night

2012;

Waning Moon and Agitated Clouds

2010;

OIL ON ALUMINUM FLASHING

Lois Dodd has long been fascinated by the sky, especially the night sky, an important subject matter for Ryder as well. Working in a small size but large scale, as did Ryder, she has painted on pieces of aluminum roofing material in a continuing series of night pictures that explore the endless sights of the cosmos, of the moon, clouds, and open spaces. Seen together, they appear as snapshots of the universe pulling us together in a unified, if infinitely varied, view of the world.

Loan courtesy of Alexandre Gallery

Emily Auchincloss

Ampersand

2018 and Book, 2018 – Ongoing

GOUACHE AND GRAPHITE ON ARCHIVAL MATBOARD;

GOUACHE AND GRAPHITE ON BOUND BOOK OF LAID PAPER

Artist’s Statement:

In my paintings, simple objects end up in complex relationships – transmuting figure/ground relationships, space is broken open and rearranged, shapes touch and converge while color sings its siren song – the paintings are phrases, stanzas, of how we touch and feel the space around us. About how color can be felt in the modern body.

Like Ryder, I work in small scale. The size of Ryder’s works is something we cannot discount – it showed a way for artists to make meaningful work that does not have to follow the hubristic Modernist macho project of expanding to fill a wall – art that looms over you, art that shouts. Instead, making small scale work can be an act of resistance – against the crass economies of scale, of amassing resources, of projection of power and might. Creating art that does not shout, but listens.

Loan courtesy of Emily Auchincloss