Cultural Communities and Identities

Cultural Communities

A haven for immigrants

Since the seventeenth century, New Bedford has been a major destination for immigrants, a city shaped by the diversity of its residents.

Today, new arrivals live alongside descendants of Wampanoag Indians and the many ethnic groups that have made New Bedford home over more than 300 years.

The influence of whaling

As the whaling industry grew, the need for crewmen for ships influenced New Bedford’s ethnic character. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, crews were drawn from men of African, British, or Native American ancestry who had settled in and around the city. Beginning around 1800, increasing numbers of whalemen from the Azores and Cape Verdes, islands governed by Portugal, joined the crews of New Bedford vessels and began to make their homes in the city.

Fleeing the famine

As a potato famine ravaged Ireland in the mid-nineteenth century, many residents fled and established a large New Bedford Irish community.

Industrialism

Like other American cities, New Bedford was transformed by nineteenth-century industrialization, which brought an influx of immigrants, who wanted jobs and relief from difficult conditions in their native lands. Although only fourteen percent of the city’s population was foreign-born in 1865, the development of the textile industry swelled that percentage to 40.9 by 1900.

English residents doubled from 1865-1890, many arriving from mills in Lancashire to become weavers and spinners in New Bedford.

Portuguese from mainland Portugal and the Madeira islands began arriving after 1870 to work in the mills, joining earlier immigrants from the Azores and Cape Verde Islands to make the Portuguese the largest cultural community in New Bedford today.

French-Canadians also came to work in the mills in the years after the end of the Civil War (1865). For a time around 1900, they were the largest group of immigrants in New Bedford.

A rich tapestry

In addition, immigrants from the world over have contributed to the rich tapestry of cultural life in New Bedford. Significant Dominican, Puerto Rican, South American and Asian communities have also developed in recent years.

Traveling Exhibition

Yankee Baleeiros! The Shared Legacies of Luso and Yankee Whalers

The traveling exhibition celebrates the interwoven Luso-American stories of the Azorean, Cape Verdean, and Brazilian communities to the United States from early immigration in the 18th century through the latter half of the 20th century. Learn more

African-Americans in New Bedford

African-Americans have been a presence in New Bedford since its early days.

Runaway and freed slaves were attracted by the Quaker majority’s early (1716) opposition to slavery and the prospect of employment on whaleships. Free seamen from continental Africa, the Cape Verde Islands, and the Caribbean also became part of the African-American heritage of New Bedford.

Finding jobs at sea

Blacks served among the crews of whaleships before the American Revolution (1775-1783). Some were runaway slaves, like Crispus Attucks, who spent twenty years as a whaler and merchant seaman, before he was killed in the Boston Massacre (1775), or John Thompson from Maryland, who found safe haven on the New Bedford Bark Milwood on its 1842-1844 voyage. Others were free Africans or West Indians. It is known that more than 3,000 African-Americans served on New Bedford whalers between 1803 and 1860. However, after the turn of the twentieth century, Cape Verdeans became the backbone of the whaling industry.

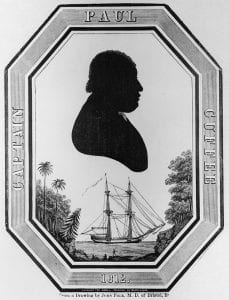

Mates and masters

Although a number of African-Americans served as boatsteerers (harpooneers) and a few as mates (officers), they rarely rose to the post of captain. Absalom Boston, Pardon Cook, and Paul Cuffe were three notable African-American whaling masters. There were also a few African-American captains who went to sea with all-African-American crews. They represented a small percentage of all whaling vessels.

The Temple toggle iron

The toggle harpoon head developed in 1848 by Lewis Temple, an African-American blacksmith in New Bedford, was the most successful of all harpoon designs.

Decline in number of African-American seafarers

After 1830, there were decreasing numbers of African-Americans on whaleships. During the 1840s, there were an average of two per vessel; and one or none during the 1850s. Increasingly, African- Americans were given less favored positions. As the number of white immigrants increased, they competed with African- Americans for jobs.

Frederick Douglass

After the American Revolution (1750-1783), the northern states abolished slavery. Massachusetts took the step in 1780. New Bedford became an important stop on the “underground railway,” a network of people opposed to slavery, who hid runaway slaves in homes and churches. Frederick Douglass found refuge in New Bedford from 1837-1841. He worked at Coffin’s Wharf before becoming a renowned abolitionist, orator, politician, and writer.

Other notable African-Americans in New Bedford

Elizabeth Carter Brooks, daughter of a freed slave, founded the New Bedford Home for the Aged in 1897.

William H. Carney — for his service during the Civil War, in the 54th regiment — he became the first African-American to win the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Dr. Juan Drummond was the first woman of her race to become a physician in turn-of-the- century southeastern Massachusetts.

James Henry Gooding, served as a corporal in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, a famous black regiment, which fought with valor during the Civil War. Gooding, who petitioned President Abraham Lincoln for pay for black soldiers, later died at Andersonville, one of 13,000 Union soldiers who died in that Confederate prison camp.

Historic landmarks

Local organizations plan to preserve three houses on Seventh and Spring Streets once owned by Nathan and Mary Johnson, local African- American abolitionists. Douglass and other slaves who escaped from servitude were hidden in these houses.

Black Heritage Trail

The trail commemorates some of the significant landmarks of African-American history in New Bedford, and local cultural organizations have presented related exhibits and programs. A recent exhibit by the Old Dartmouth Historical Society-New Bedford Whaling Museum explored the role of local African- American soldiers in the Union army during the Civil War.

The Portuguese Connection

Today, more than 55% of the population of New Bedford claims Portuguese forebears. The story of how this community developed is another aspect of whaling’s legacy.

Portuguese immigrants came to New Bedford primarily from four locations:

The Azores, nine islands in the Atlantic, settled by mainland Portugal, which lies 840 miles to the east.

Madeira, two islands 500 miles southeast of the Azores, off the northwest coast of Africa, also colonized by Portugal.

Cape Verde Islands, off the coast of Senegal in Africa, formerly a territory of Portugal.

Portugal, the European nation located west of Spain and north of Morocco. Although residents of all four areas share a common Portuguese heritage, each one has distinctive customs and traditions.

The Portuguese connection with New Bedford developed from eighteenth-century whaling. Prevailing winds made the Azores first port-of-call. As ships took on supplies and crew in the Western Islands, as they were traditionally known, the stage was set for Portuguese immigration to New Bedford.

After whaling in the Azores, it was customary to hunt whales around the Cape Verdes and along the coast of Africa before cruising southwest to the Brazil Banks off the east coast of South America, and then home to New England. After 1800, New England whalers ventured into the Pacific and Indian oceans on longer and longer voyages.

There were three waves of Portuguese immigration to the city

1800-1870: The first to arrive in significant numbers after 1800, were the Azoreans. Eager to find economic opportunities or to escape conscription into the Portuguese army, they left their islands as crewmen on Yankee whalers and settled in New Bedford. Cape Verdeans began arriving after the 1850s. A significant part of the population was descended from white Portuguese colonists and black African slaves and spoke a dialect of Portuguese known as “crioulo” or “caboverdeano”.

1870-1924: Residents of Madeira and mainland Portugal joined Azoreans in looking for opportunities in emerging industries, particularly the textile mills, of New Bedford.

1958-present: Portuguese immigration, which had slowed to a trickle from 1917 to 1924, resumed when restrictive immigration laws were eased because of devastation caused by a volcanic eruption. Today, recently enacted restrictions have reduced Portuguese immigration significantly.

Portuguese influence in the American whale-fishery Azoreans and Cape Verdeans, who were used to hard work, made desirable crew members for whaleships. Many Portuguese seamen from New England and the islands served on American whaleships during the nineteenth century. In the 1860s, they comprised up to 60% of whaling crews. They were often willing to accept the lowest shares of the profits of a whaling voyage, in their eagerness to leave the islands and make new homes in America. Like African-American seamen, they might earn the position of captain or mate but the biases of Yankee shipowners were against them. Nevertheless, a significant number of Portuguese immigrants became mates or masters of whaleships. From the turn of the century until American whaling ended in the 1920s, Portuguese captains and crews were the dominant force in the industry.

New Bedford enjoys a sister city relationship with the city of Horta, Fayal, in the Azores, while Dartmouth is linked with the Azorean town of Povoacao, Saint Michael.

Manjiro: The Japanese Boy Who Discovered America

Shipwrecked!

In January 1841, young Manjiro Nakahama and four friends were caught in a fierce storm as they fished off the Japanese coast. They drifted for weeks and then swam to an uninhabited island.

The John Howland to the rescue

After months on the island, a whaleship from New Bedford rescued them on June 27, 1841. Captain William H. Whitfield, impressed by young Manjiro’s intelligence, decided to take him to America. The sixteen-year-old boy was alone with his rescuers after his companions left the ship and remained in Hawaii. The xenophobic government of Japan, the Tokugawa Shogunate, would not permit them to return after contact with foreigners.

An American education

The John Howland sailed into New Bedford harbor almost two years later in May 1843. Manjiro lived first with a friend of Capt. Whitfield’s, and later on the captain’s farm. He attended school and studied navigation and whaling with the captain. He was known locally as John Manjiro or John Mung.

The long journey home

In 1846, Manjiro became a hand on whalers and merchant ships. Three years later, he set out for Japan via the California Gold Rush (1849); eventually reaching his native land in 1851, after an absence of ten years.

An uneasy homecoming

The Tokugawa Shogunate greeted Manjiro with suspicion and harsh interrogations, although he was eventually allowed to remain in Japan. For the rest of his life, he participated in the transformation of Japan from feudal to modern nation, working as interpreter, translator, shipbuilder, whaler, and teacher.

Heart of a Samurai, a biographical novel by Margi Preus, is based on the life of Manjiro. Grade level: 4-8

Sister Cities: Tosashimizu and New Bedford/Fairhaven

A magnet for Japanese visitors

The New Bedford/Fairhaven area is today an important destination for tourists from Japan, who are attracted by the historic sites related to the life of Manjiro Nakahama, the first Japanese national known to have been educated in the United States before he returned to Japan in the nineteenth century.

A family connection

When a whaling captain, William Whitfield, rescued a shipwrecked boy from a bleak island off the coast of Japan and brought him home to the New Bedford/Fairhaven area, he initiated an international relationship between families and nations that has survived for over 150 years.

After his American adventure, Manjiro returned to Japan where he raised a family and worked as a translator, interpreter, and teacher, as well as shipbuilder and whaler. After both Manjiro and Capt. Whitfield died, their families continued to correspond. Dr. Toichiro Nakahama, Manjiro’s eldest son, presented an ancient samurai sword to Fairhaven on July 4, 1918. A year later, the Japanese emperor honored Marcellus P. Whitfield with the Sixth Order of the Rising Sun, in recognition of his father’s kindness to a Japanese subject.

A bicentennial visit

In May 1976, Manjiro’s great-grandson visited the places where his grandfather learned English, navigation, and the whaling trade. Eleven years later, the Japanese Consul-General in Boston suggested a formal sister city relationship between Tosashimizu, Manjiro’s birthplace, and New Bedford/Fairhaven.

An imperial visit

The then Crown Prince and Princess, now Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko, honored the new sister cities by visiting New Bedford/Fairhaven on October 4, 1987. Among the speakers on that festive occasion were the great- grandsons of Manjiro Nakahama and William Whitfield. Cultural exchange: Today, the cities maintain ties through exchanges of students and baseball teams, and participation in the bi-annual Manjiro festival.

Other Sister Cities

Horta, Fayal, Azores and New Bedford; Povoacao, Saint Michael, Azores and Dartmouth.

Visit Pacific Encounters: Yankee Whalers, Manjiro, and the Opening of Japan– a New Bedford Whaling Museum on-line exhibit, to learn more.