Complicated Legacies: Museum History, White Supremacy, and Sculpture

New Bedford Whaling Museum

Little Braitmayer Gallery

October 11, 2024 – October 13, 2025

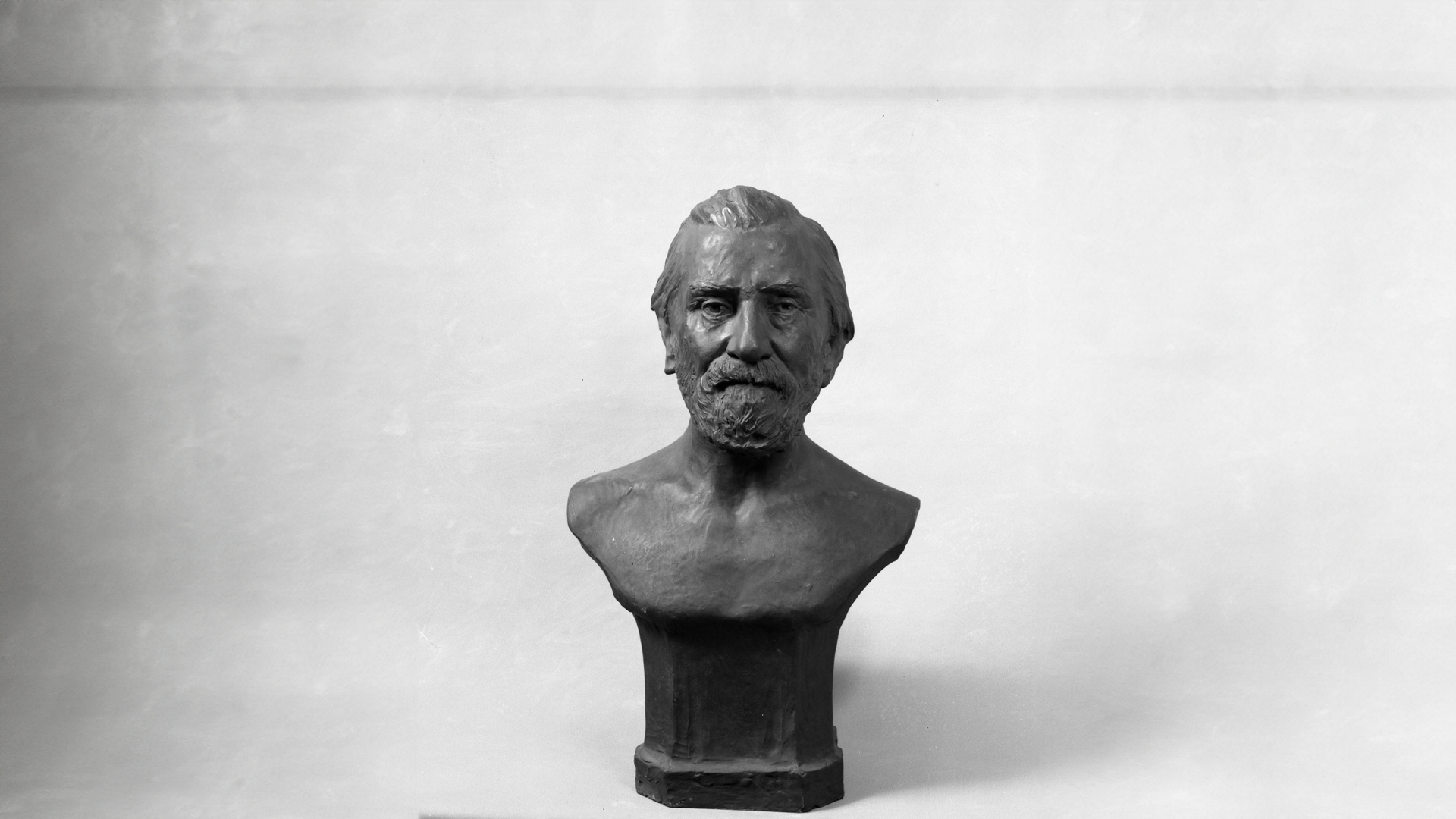

The New Bedford Whaling Museum (NBWM) was founded as the Old Dartmouth Historical Society (ODHS) in 1903 and has been collecting and exhibiting for over 120 years. Its original purpose was to collect and interpret the social and cultural history of New Bedford and the surrounding region of towns in Massachusetts—New Bedford, Acushnet, Fairhaven, Dartmouth, and Westport—known as “Old Dartmouth.” New Bedford, a community on the southern coast of Massachusetts, was the largest commercial whaling center in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1914, the Society received an extraordinary gift of $75,000 from Emily Bourne, whaling fortune heiress and daughter of Jonathan Bourne, to erect a new building adjacent to the Old Dartmouth Historical Society’s museum in downtown New Bedford. It would include a half scale model of her father’s most lucrative vessel, the Bark Lagoda. When the Jonathan Bourne Memorial Whaling Museum at the Old Dartmouth Historical Society opened in 1916, the vaulted two-story gallery housed the impressive half-scale model and a bust of Jonathan Bourne made by vaunted American sculptor John Gutzon Borglum (1867-1941).

Borglum was a celebrated artist, widely revered for his work on Mount Rushmore, statues of Union General Philip Sheridan and Abraham Lincoln. He was also a staunch White supremacist, xenophobe, nativist, and racist, who was actively involved in the Ku Klux Klan and pro-Confederacy commemoration, and was the first architect of Stone Mountain in Georgia. A project organized by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Stone Mountain memorializes Confederate General Robert E. Lee and glorifies and promotes the racist ideology of the “Lost Cause.” Plans for Stone Mountain launched in 1915, coinciding with the release of D.W. Griffith’s pro-Klan film The Birth of a Nation, which was famously screened at the White House by US President Woodrow Wilson. Wilson won the Presidency in 1912, supported segregation, and held racist ideologies and a belief in the “Lost Cause” narrative. 1915 also saw a dramatic rise in membership in the Ku Klux Klan, which reformed in that year in Georgia and, by the mid-1920s, had over a million members across the country. Massachusetts enrolled almost 131,000 members, while Rhode Island had over 20,000 members. Enrollment in the KKK did not define the bounds of racism; white supremacy was widespread outside of formal member rolls. Organizations like the NAACP and the CPUSA and individuals rallied to fight racism, antisemitism, and xenophobia, often organizing campaigns and promoting social activism.

For over one-hundred years until 2020, the bust of Bourne made by Borglum sat on a plinth overlooking the Lagoda. The murder of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis, MN in May of that year and the subsequent and ongoing conversations about police violence, racial injustice, and Black Lives Matter, prompted internal conversations at the museum about Borglum’s beliefs and the work of sculpture in public view. While those conversations developed, the bust was removed from public view. In 2024, on the 110th anniversary of Emily Bourne’s extraordinary gift, we are placing the bust back on view and inviting visitors to engage with the complicated legacies of an institution, an artist, and an object.

This exhibition asks, what do we do with a bust created by someone who held deeply problematic racist ideologies? Do an artist’s beliefs impact how we interpret a sculpture? Is a sculpture like this one defined by the politics of the maker, patron, or subject? What were the Bourne’s politics, and what made Emily decide to commission the bust from Borglum in 1916? How might the museum, in its long history, also have supported racist ideologies or worldviews? How can we confront these histories and engage audiences in conversation about the ongoing legacies of historical harm, and racial and social injustice today?