The Wider World & Scrimshaw

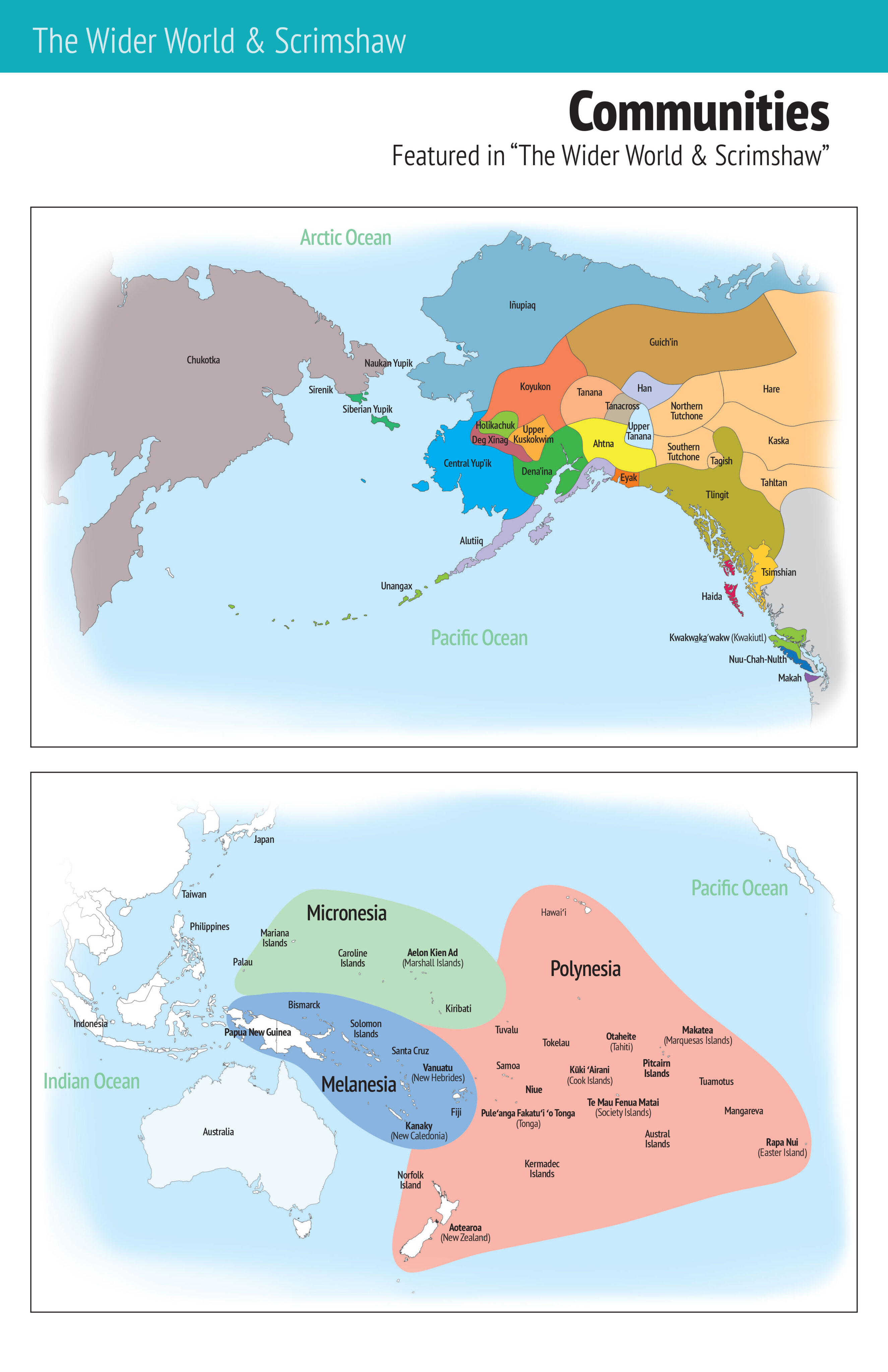

Many Native communities across New England and the Pacific world—including Oceania, the Pacific Northwest, and Arctic–have cosmologies related to whales, distinctive maritime traditions involving marine mammals, and vibrant carving styles. They were also impacted by colonial occupation, American cultural influence, and commercial whaling.

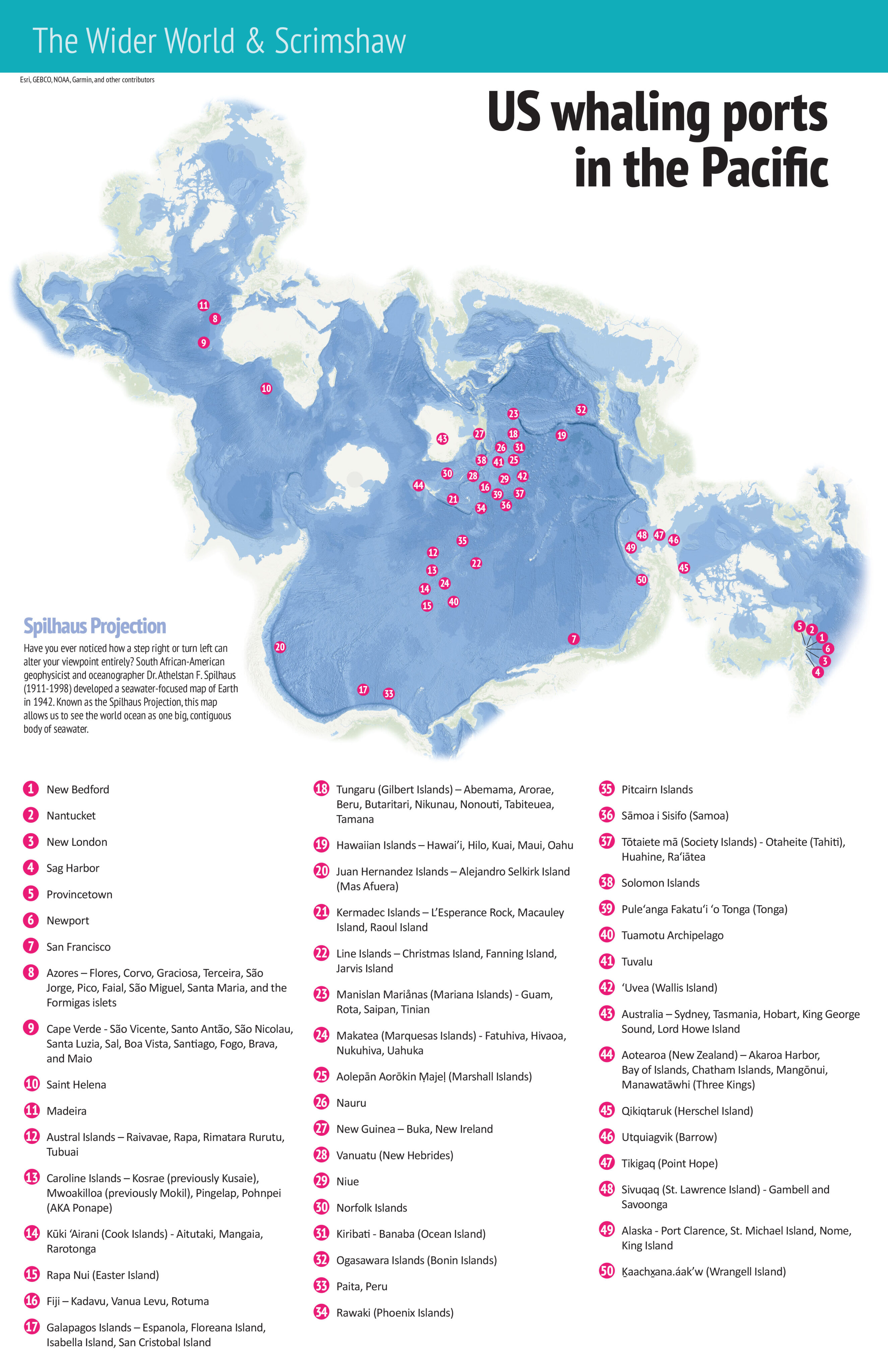

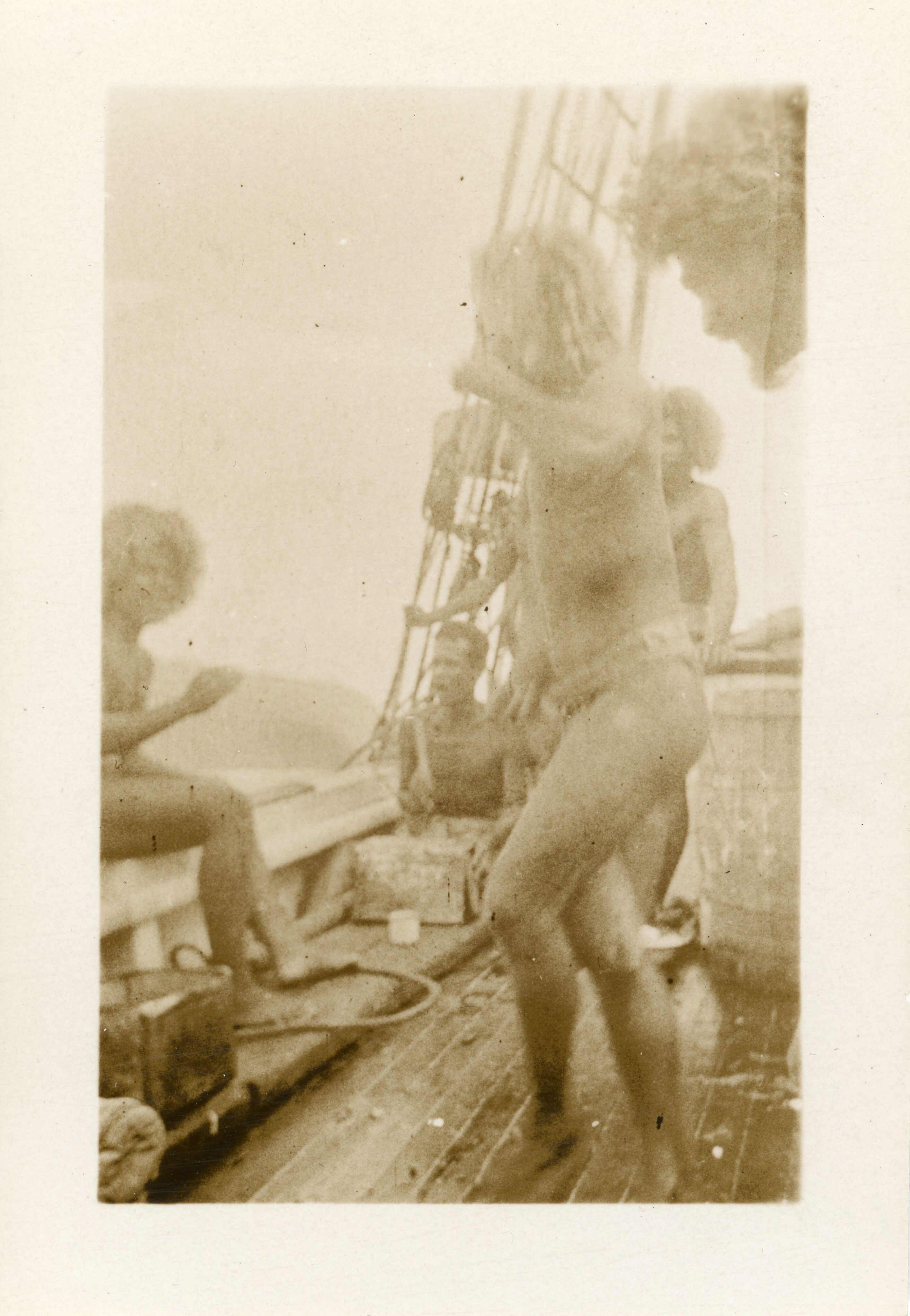

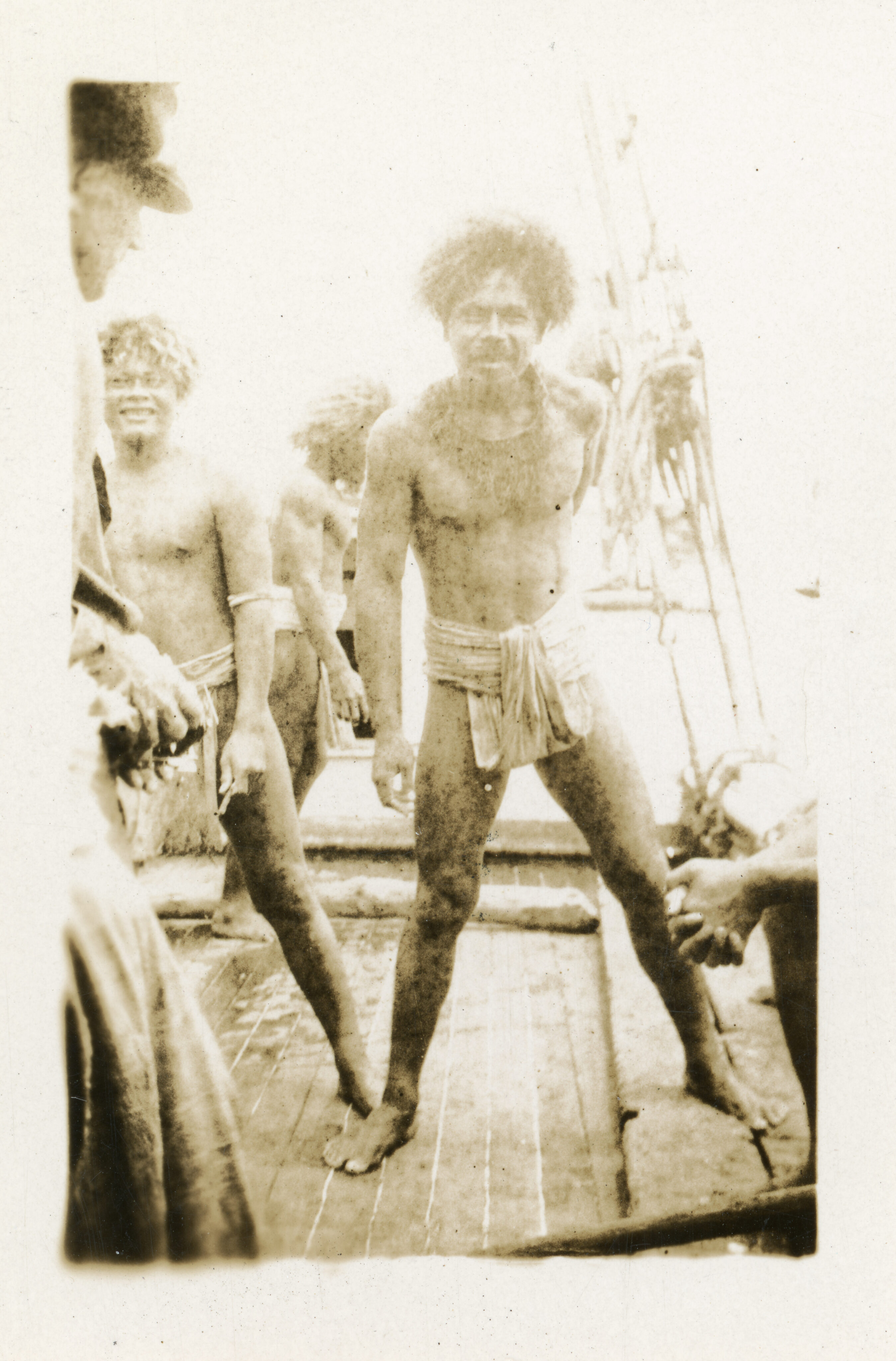

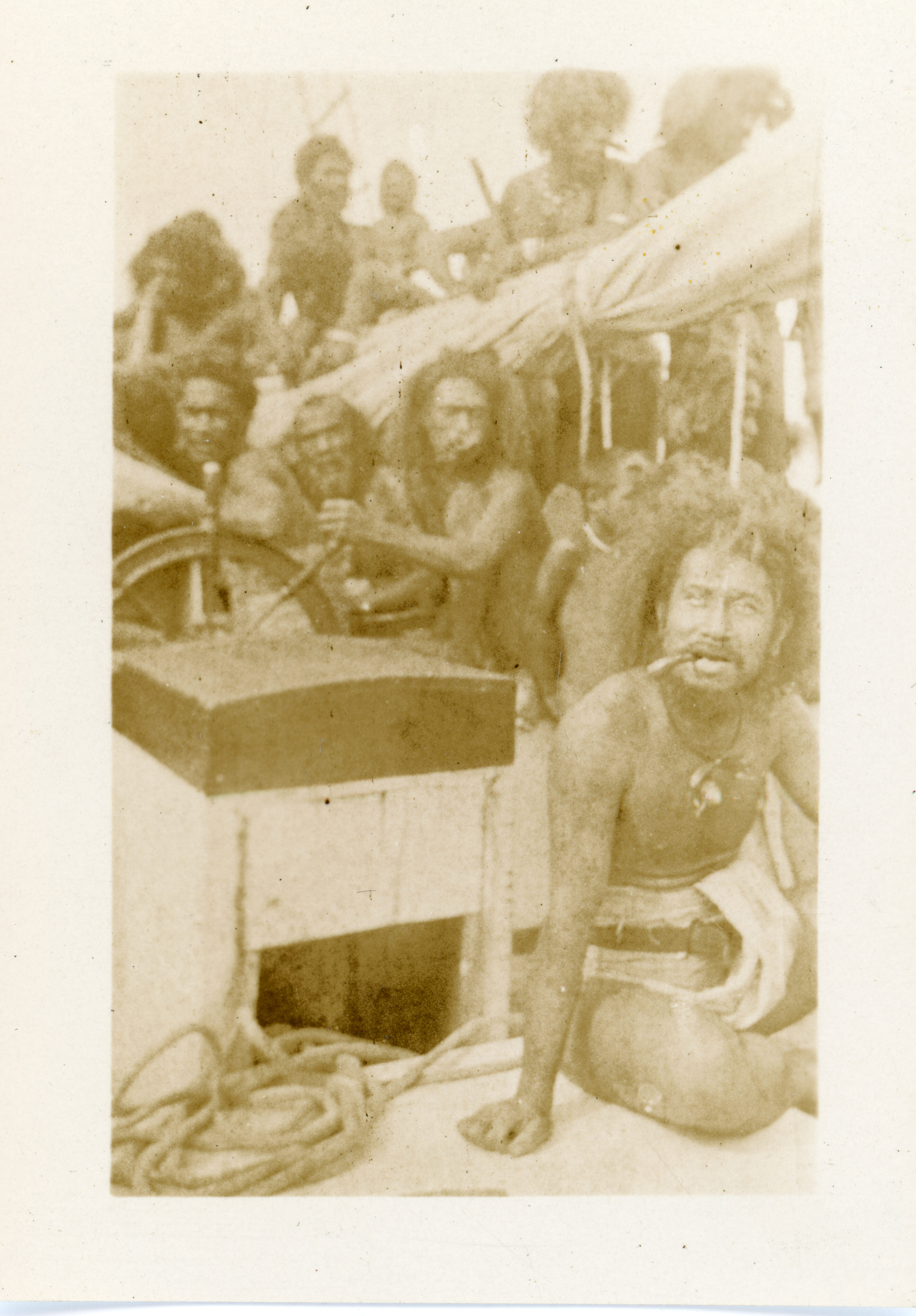

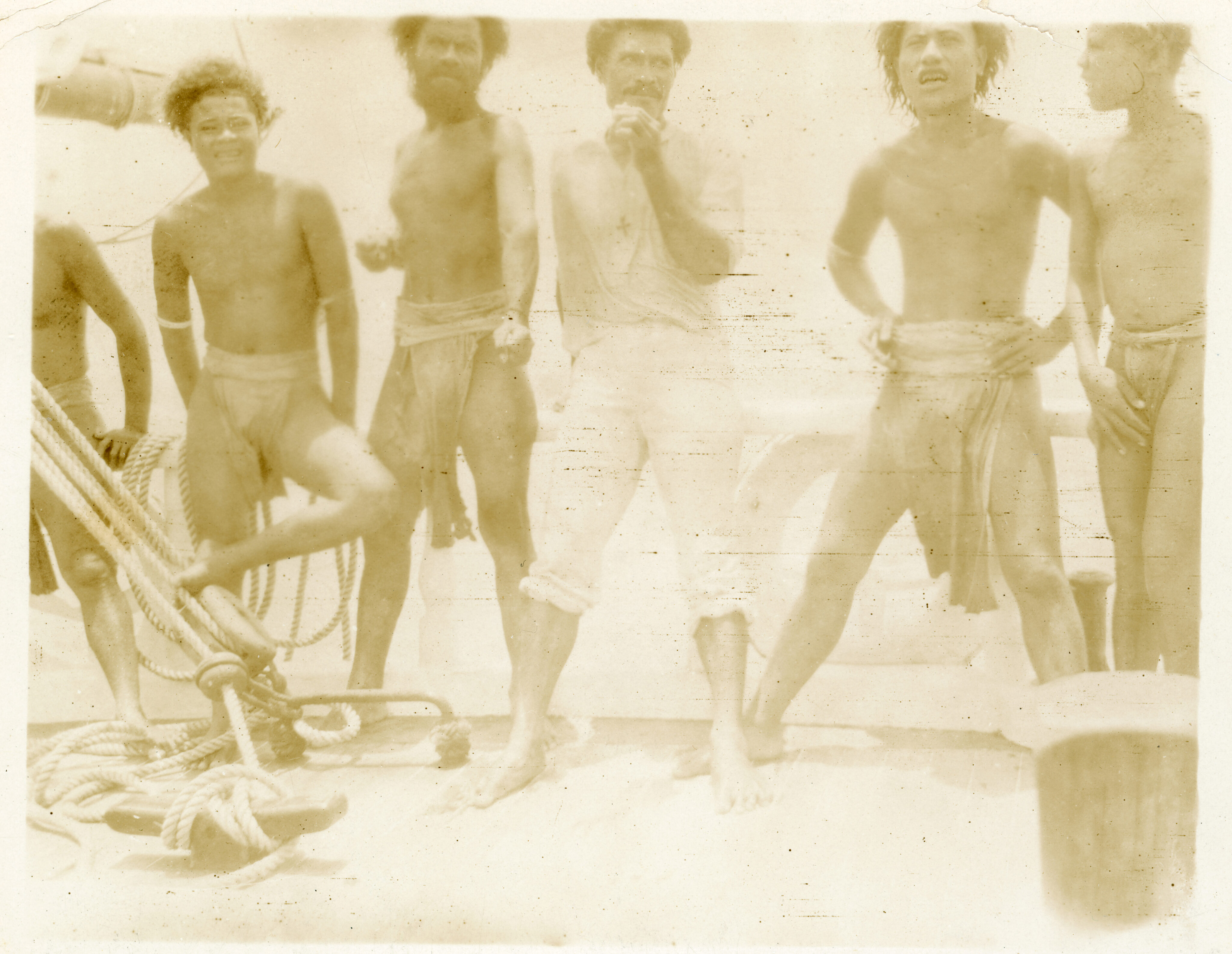

Starting in the 1830s, diverse communities came into contact as US whaling vessels traversed the Pacific to extract natural resources, including toothed and baleen whales, seals, walrus, and other marine animals. This extractive economy drove global exploration and trade, decimated indigenous species, forced settler colonial agendas, and affected cultural exchange and adaptation. US whaleships stopped at regular locations within this vast territory. They established colonies, shore whaling stations, and trade networks, and picked up supplies, materials, and crew. Because of this, US whaling vessels were very diverse. Crews included Black men (free and formerly enslaved), Native Americans, immigrants to New England, Azoreans and Cape Verdeans, US-born, European-descended men, and Pacific Islanders.

This exhibition explores the carving traditions that emerged along whaling routes in the Pacific world, from New Bedford, Massachusetts to Aotearoa and Utqiagvik. One example is scrimshaw, defined as a decorative, folk, or vernacular art made by whalers on the body parts of whales. But scrimshaw was just one of many carving practices across the Pacific world. Setting scrimshaw in conversation with other forms of carving allows us to ask questions about influence, exchange, and tradition. How did whaling (internal or external) impact communities and their unique art forms? How did cross-cultural encounters influence the items produced? How do people relate to one another through carved material culture and marine mammals?

Ultimately, this exhibition is about mobility and cultural and material exchange. It connects the historical and contemporary, linking the depletion of natural resources in the past with ongoing settler colonialism today. The stories encompassed within are about survival, of species and of communities. They speak about the future, and what we, collectively and in solidarity across the human-animal world, will make of it.

Wave sounds

Setting the Stage

Who comprised the crew of a US whaleship? Where did the vessels go? What knowledge did US settlers have about Indigenous communities? These introductory items speak to the diversity of whaling crews, their global ports, and general knowledge people in the United States had about tribal territories.

Silvia Grinnell’s needlework was made around 1805 after a new map of North America that included the recent Louisiana Purchase. At the age of thirteen, the New Bedford-born schoolgirl displays an astute knowledge of sovereign Native nations. By the 1830s, Wampanoag, Mohegan, Pequot, Narragansett, and Shinnecock men served widely on US whaleships. Amos Haskins, an Aquinnah Wampanoag man from Noepe (Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts), captained the Massasoit in the 1850s. His daguerreotype shows a confident leader. In 1822, the Industry sailed from Nantucket with Absalom Boston as captain of an all-Black crew. Both underscore the opportunities available to men of color in the whaling industry. Captains also hired on crew at various ports, further diversifying their ranks. An 1857 ambrotype by a German American studio owner in Hawaiʻi shows the Arctic whaler Benjamin Tucker in Honolulu. Another circa 1895 photograph by Sophie Porter, a whaling captain’s wife, shows the Navarch at Herschel Island on the Beaufort Sea. These examples illustrate the geographic range of Pacific whaling, the diversity of whaleships, and the mobility of individuals within this sphere in the 1800s.

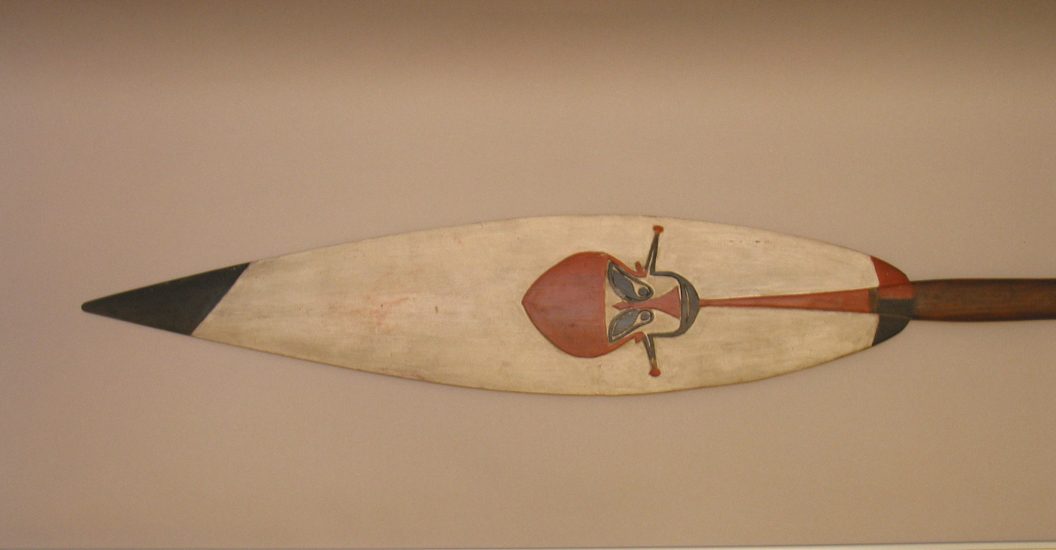

A paddle carved by Jonathan James-Perry and scrimshaw pin by Patricia James-Perry celebrate Aquinnah Wampanoag ancestral heritage and intergenerational legacies, and underscore local Indigenous connections to whaling and whales.

Watercraft

The communities represented in this exhibition are all sea faring cultures of the Pacific world. Model boats from New England, Inuit nunaat, Iñupiat territories, the Cook Islands, Yukatat and Haida lands, Hawaiʻi, and Niue underscore how the sea brings these maritime cultures together and sustains them.

Materials

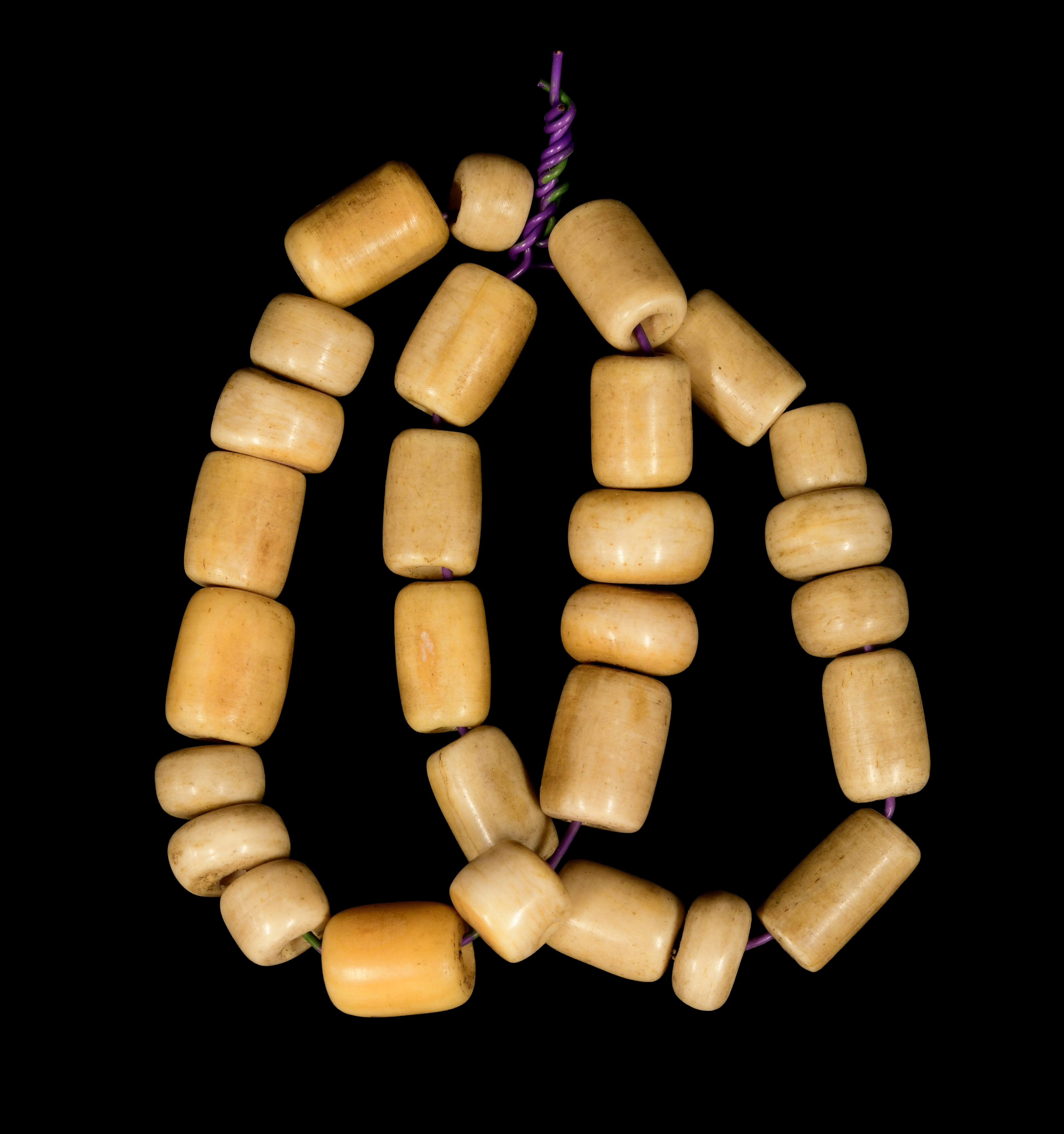

There are many different kinds of materials used in the creation of items in this exhibition. Many of these materials come from living things – plants and animals—and speak to diverse ecosystems and human relationships to specific locales. These materials also circulated within systems of economic and cultural exchange—as gifts, items for trade, and saleable commodities. Whalers and community members hunted, gathered, grew, and collected such materials and used or exchanged them throughout the Pacific and Arctic.

Who participated in the collection and trade of these various materials? Who hunted the walrus and the sea turtle? Who cultivated the coconut groves, stripped the bark from the paper mulberry tree? Who prepared the whale teeth, carved the ivory, fitted the silver, or shaped the coconut shell? Might we think of objects in the exhibit as collaborations between growers, harvesters, and carvers, each bringing different cultural knowledge to the production of an item for trade, personal use, or sale? And what of the animals and plants, whose bodies and material went into their production? Can we count them within this chain of extraction and creation? How many whales and walrus are in this exhibition, unnamed except as “material”?

Where Do Different Types of Whales Live?

Sperm whales (Physeter microcephalus) are a global species, found in all oceans except the Arctic. The southern right whale lives across the Southern Hemisphere, while the North Pacific right whale ranges from Baha, California, to the Bering Sea. Gray whales live along the West Coast of North America, while bowhead whales range across the Arctic and Subarctic. Other Arctic cetaceans include narwhal (Monodon monoceros), as well as the pinnipeds walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) and bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus).

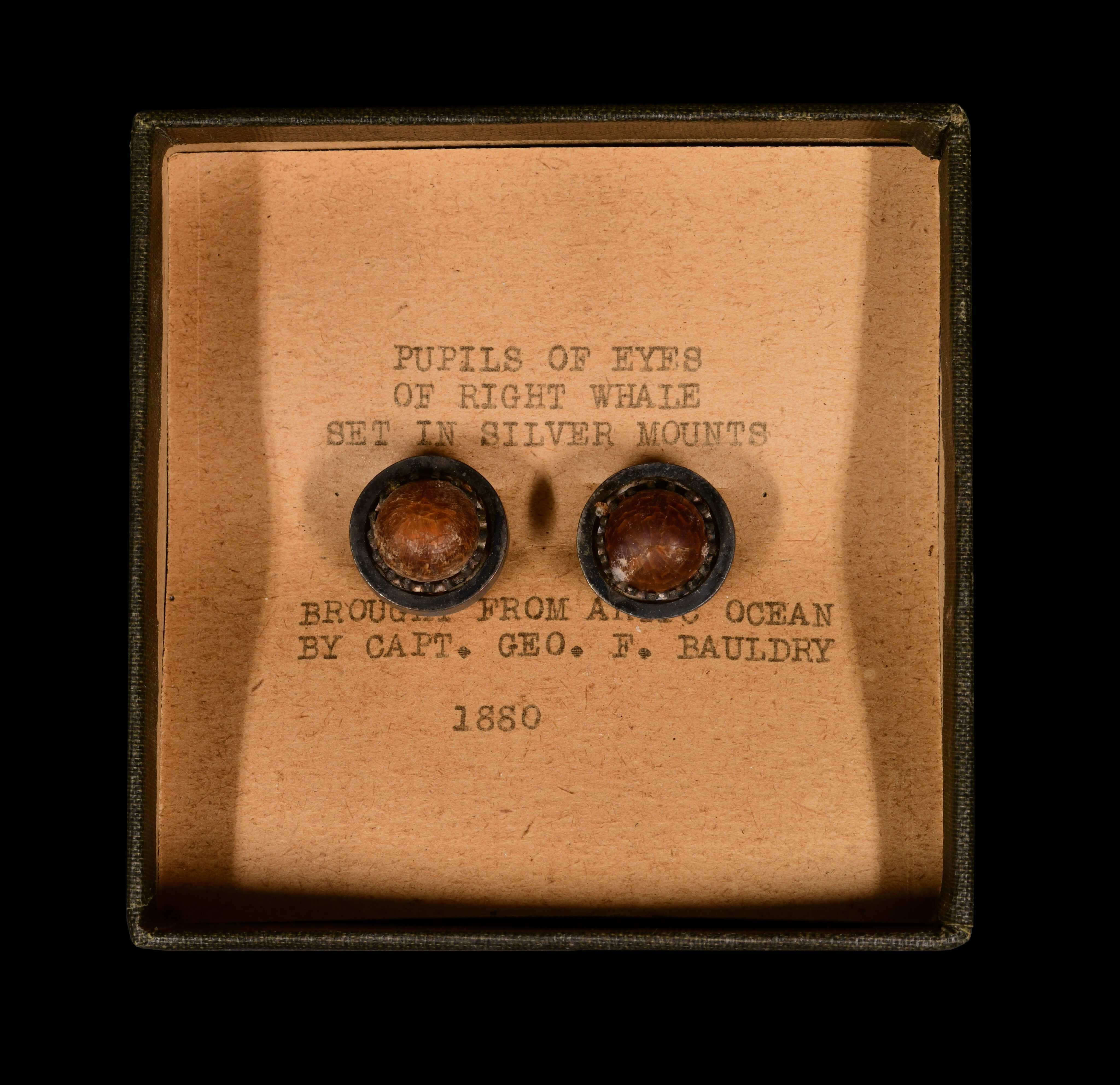

Over the 1800s, US whalers targeted Southern and North Pacific right, gray, bowhead, and sperm whales. During this period, whales—who are extremely sensitive animals—developed adaptive behavior to evade hunters. Despite this, approximately four hundred and thirty thousand whales were killed by US whalers, the majority in the Pacific and Arctic Oceans. Gray whales were intensely targeted from 1846 to 1874. Bowhead and walrus hunting started in 1849. In all, one hundred and forty-eight thousand walruses were killed, the majority between 1868 and 1883. This environmental destruction had ecological and human consequences. Many Native communities, who relied on local animals for subsistence, struggled to find food and adapt to the new ecological conditions. Whalers simply moved on to the next available species.

In 2024, a gray whale was sighted in the Atlantic Ocean. Extinct in the Atlantic since the 1700s and most common in the North Pacific, gray whales may be returning due to climate change and melting sea ice and changing prey distribution. Is this adaptation at work or the recolonization of past territory?

Pacific Encounters

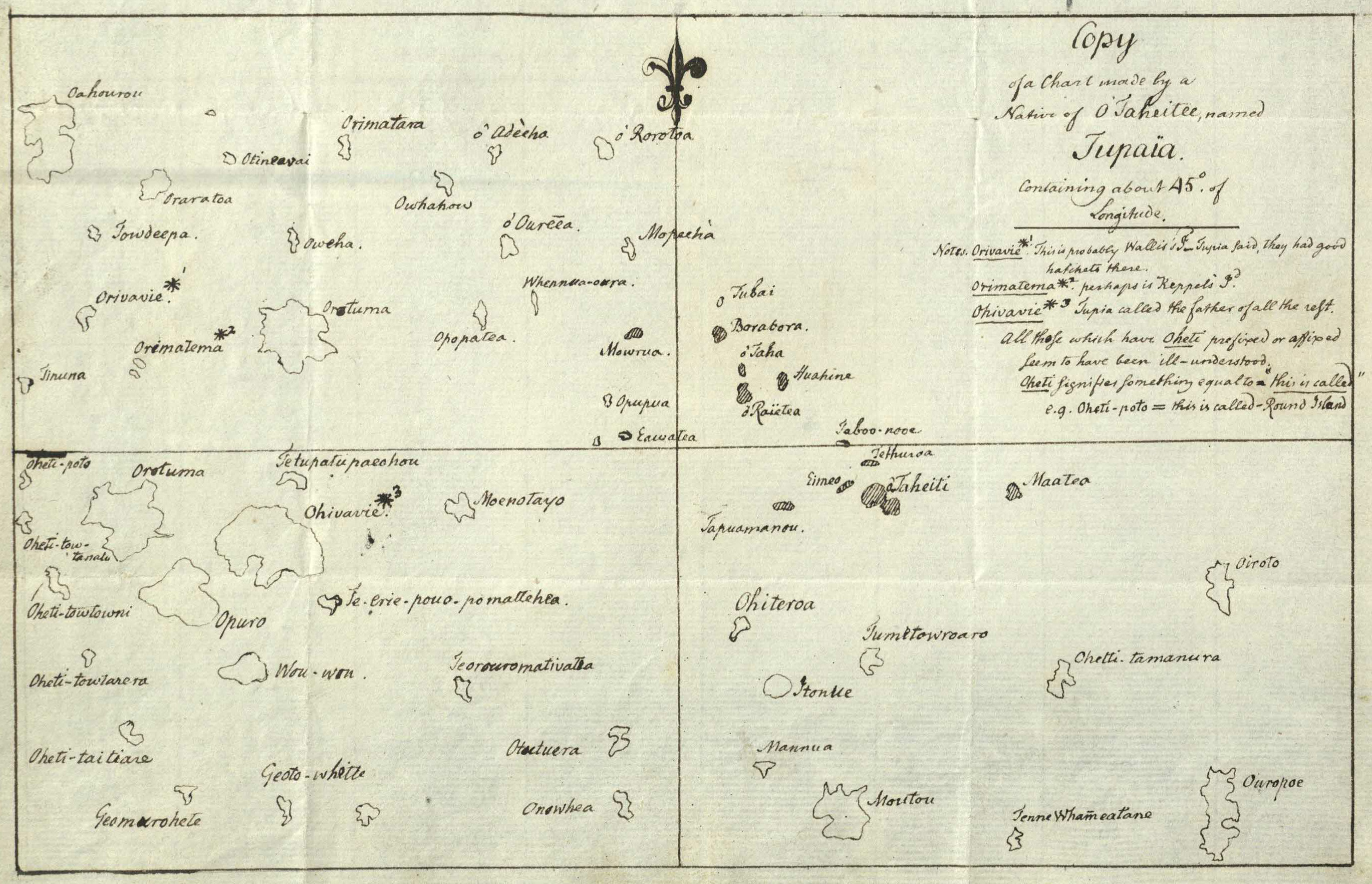

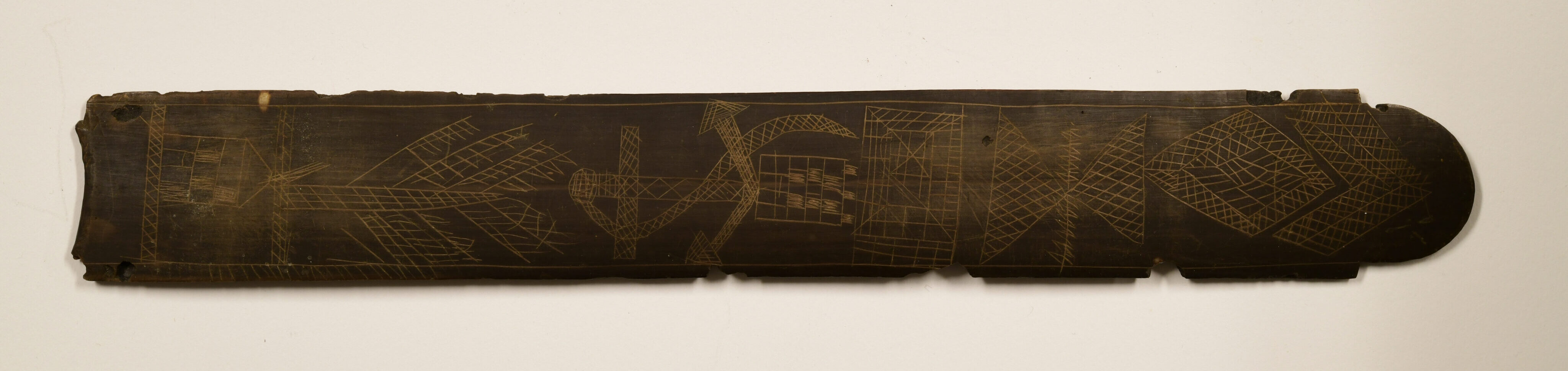

A Marshall Islands navigation chart and a busk made of whale baleen incised with a similar chart, an Austral Islands paddle and wooden busk that are both chip-carved, and a map made in 1769 by Raʻiātea priest, navigator, and interpreter Tupaia (ca. 1725-1770) on HMS Endeavour with British explorer Captain James Cook. These items bring ocean navigation, maritime traditions, and cross-cultural contact to the fore. They demonstrate cultural exchange with and Pacific Islander involvement in New England whaling ventures in the 1800s. How can we understand exchanges that occurred around the Pacific world during periods of intense colonial pressure, conflict, and cultural encounter?

Beginning in the 1790s, New England whalers began hunting whales in the Pacific, from Peru to Aotearoa (New Zealand). Merchants and Christian missionaries followed. The latter arrived in the region in 1797, bringing a new religion and moral and social order. Sometimes these individuals stayed, had families, and adapted to island life. Other times tensions erupted. By 1850, over one hundred whaling vessels visited Hawaiʻi annually. US consulates were established in Fiji in 1844, Samoa in 1856, and the Marshall Islands in 1881. Across the Pacific, ports like Lahaina, Paita, Huahine, and Apia attracted US whalers, who traded goods, signed on crew, established expatriate communities, and collected souvenirs.

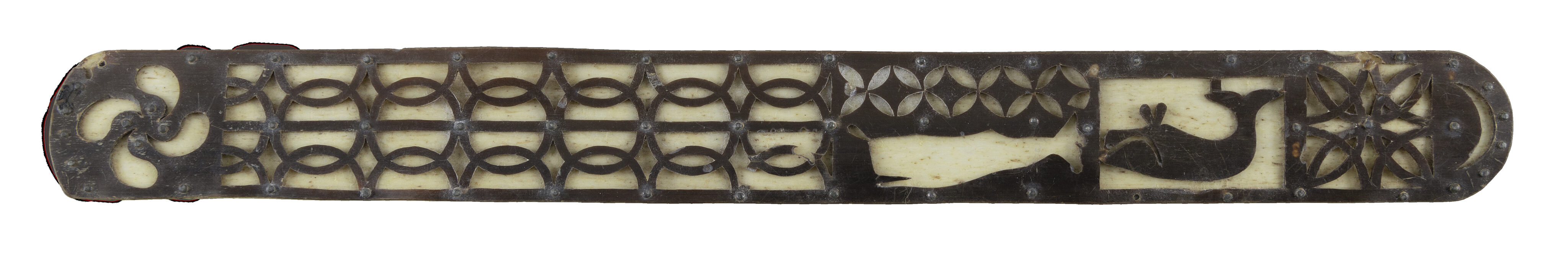

Who Were “American” Whalers?

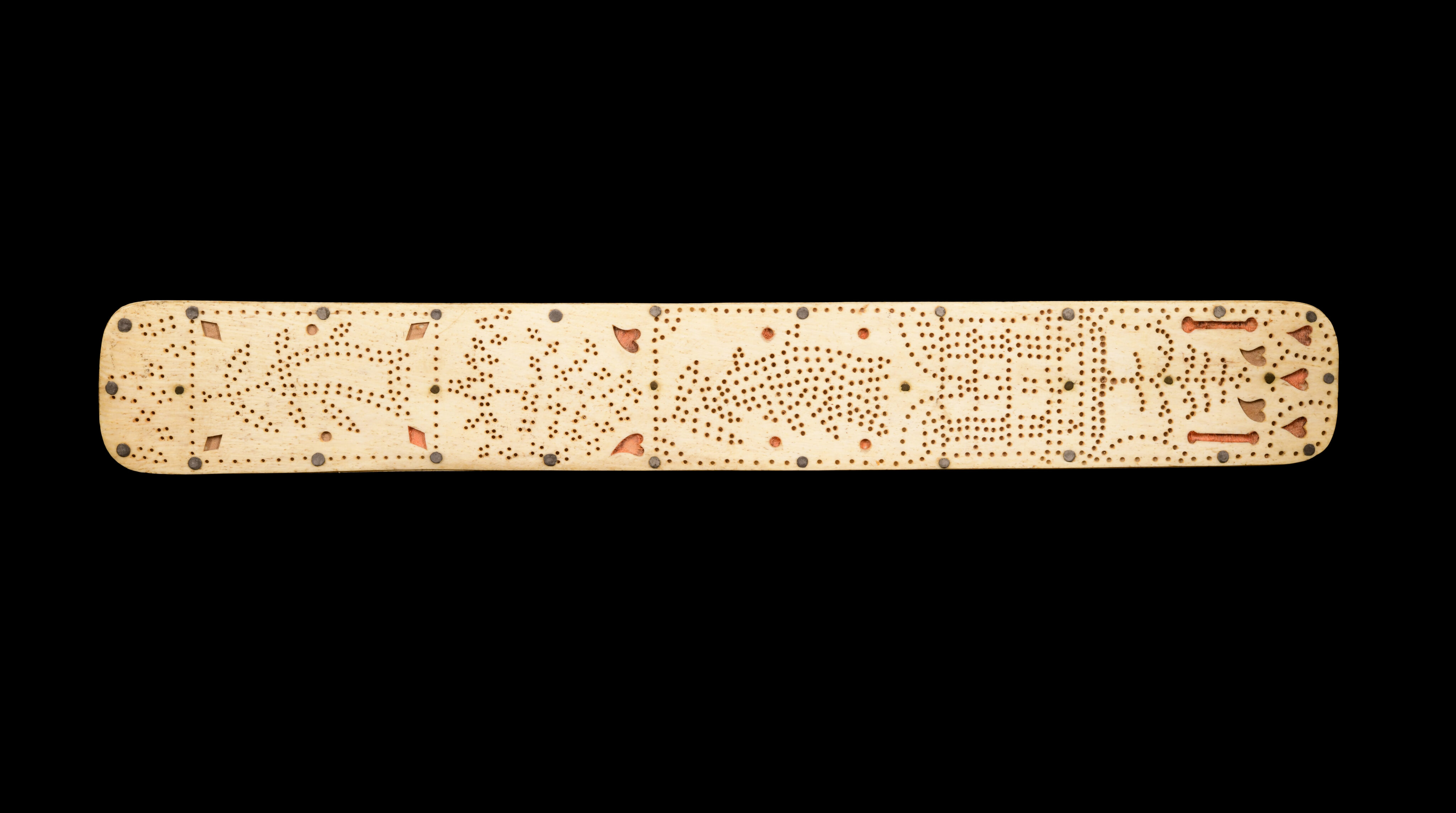

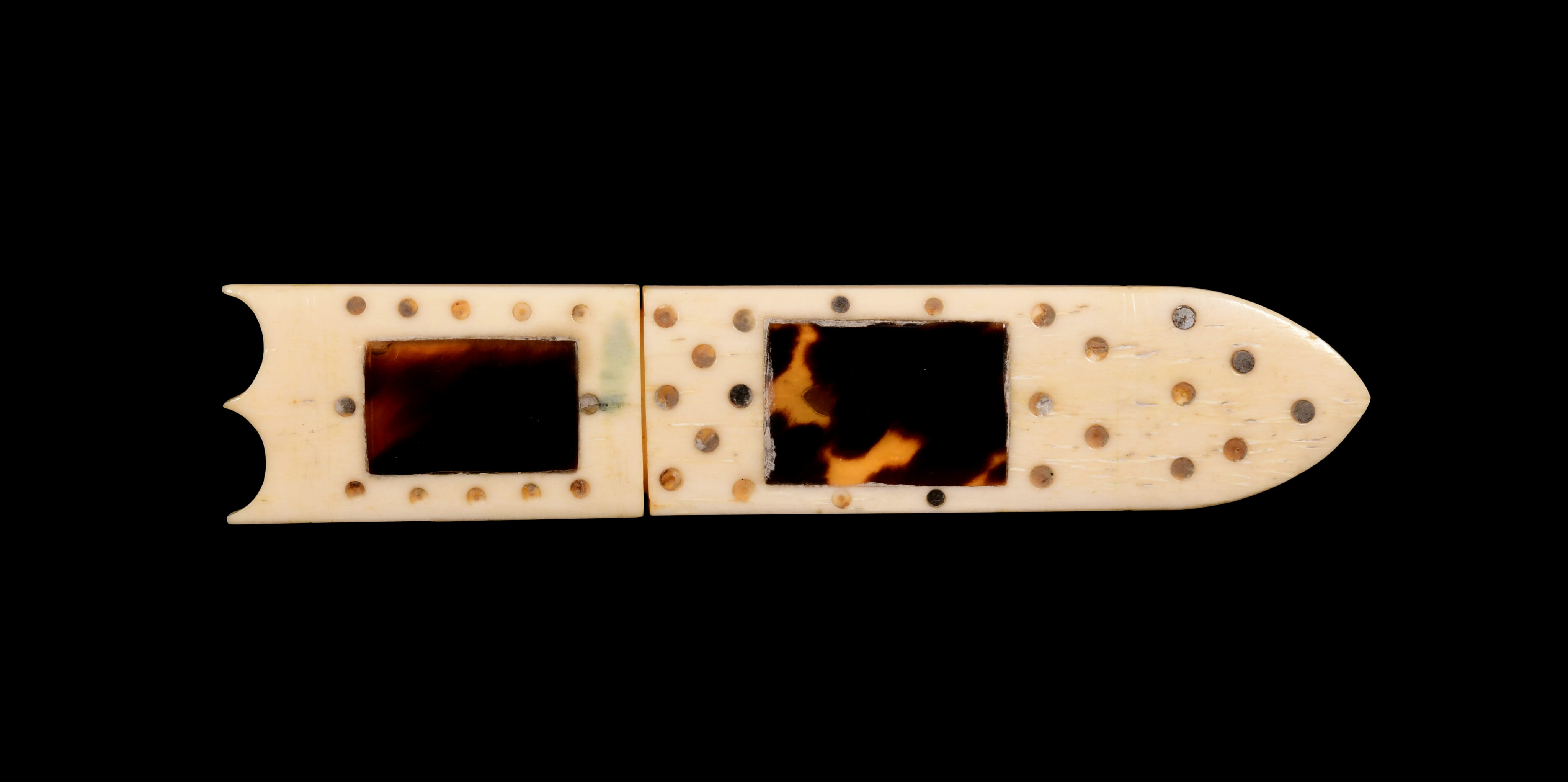

By the mid-1800s, 20 percent of crews on New Bedford whaling vessels were Pacific Islanders. The whale baleen busk is incised with a tree, anchor, and navigation chart. The name “John Gibbs” is inscribed on the back. Was Gibbs the maker or was he given the busk as a gift? Was the maker from New England or from the Marshall Islands? How did he learn to carve and what traditions or encounters informed his design? Was the navigation chart a part of his culture or a record of cultural encounter?

Navigation is a treasured form of cultural knowledge and integral to life in the Pacific. The Marshall Islands consist of over one thousand islands spread across hundreds of miles. Their charts mark islands with cowrie shells and swell and wave patterns with diagonal and curved sticks. Navigators memorized charts when they went to sea. Today such charts are protected cultural heritage.

Mapping and Indigenous Knowledge

Our spatial and ecological relationship to our surroundings, how we “know” the world and imagine our place within it, is informed by our culture. Maps are symbolic interpretations of space that demonstrate different relationships, like the communal, political, topographical, or ecological. They are symbolic and often informed by choices or biases.

This is sophisticated wayfinding, based on the careful transference of generational knowledge, continuity of tradition, and oral storytelling. Tupaia’s map is not organized by a European standard of measurement or cardinal directions. Because of this, for two hundred years Europeans thought it was wrong. It shows how Europeans devalued Indigenous knowledge and affirms Pacific Islanders’ strong sense of place within their oceanic world.

Excerpt from Tales of Taonga: Tupaia, 2019. Produced for The Coconet TV, Courtesy of TikiLounge Productions.

Tupaia was one of the most extraordinary explorers of the Pacific. His story was taken over by the narrative of Captain Cook, but now his life and significance around the Pacific is being told again. In this excerpt Pacific sailors talk about the significance of Tupaia’s map and how it illustrates Indigenous navigation knowledge utilized and shared for centuries.

Paddles, Dance Wands & Clubs

There are about twenty-five thousand islands in the Pacific Ocean. Each is distinctive. Oceanic carvings like paddles, clubs, and dance wands were made from wood and whalebone for ceremonial and utilitarian purposes along sea-faring routes in the Pacific. Examples from Papua New Guinea, the Solomon, Austral, Marshall, and Gilbert Islands, Tonga, Fiji, and Kiribati, among others, illuminate traditional carved forms and techniques.

Hundreds of thousands of items like these were collected in the 1800s by American and European mariners, traders, whalers, and settlers, and later by generations of museum curators. The vast majority are in US and European museums, where they are treated as ethnographic objects, prized for their formal qualities and utility, and framed as representative of cultural differences.

This cultural heritage ties descendant communities to their land, water, and traditions. Such items are of profound importance for Islanders today, who aim to reconnect with displaced heritage and continue ancestral traditions and artforms despite historical disruption and harm.

Pacific Trade & Adaptation

Traders in the Pacific wanted sandalwood, seal fur, mother-of-pearl, bêche-de-mer (sea cucumber), hawksbill turtle shell, and coconut oil. Islanders desired hardware and clothing. Resident agents across the islands facilitated exchange trading and served whalers coming ashore to refit vessels. Trade introduced new things, networks, and social and cultural possibilities.

Steel axes and tools were highly desirable and assimilated into traditional practices. The Tolai of Papua New Guinea use a carved, painted dance axe made of wood in funerary ceremonies. Similarly, axe clubs replaced war clubs in Vanuatu (eighty-three islands/ formerly New Hebrides). One was collected by José Goncalves Correia (1881-1954). Born in Fayal, Azores, he immigrated to New Bedford and was a whaling cooper in the Pacific. This led to an affiliation with the American Museum of Natural History, who contracted him for voyages including the Whitney South Sea Expedition (1920-1941), which visited six hundred islands and collected over forty thousand bird and plant specimens, causing the extinction of several bird species. He donated this axe club to the Old Dartmouth Historical Society in 1926 with “clubs, etc. from New Hebrides.”

Cook Islands Carving, 2021. Digital Fāgogo, Produced for The CocoNet TV, Courtesy of Tiki Productions.

Cook Islands taunga (carver) Elsie Hosking shares how she connects with her Cook Islands culture through carving and learning about Indigenous processes and art forms at Mike Tavioni’s Vananga.

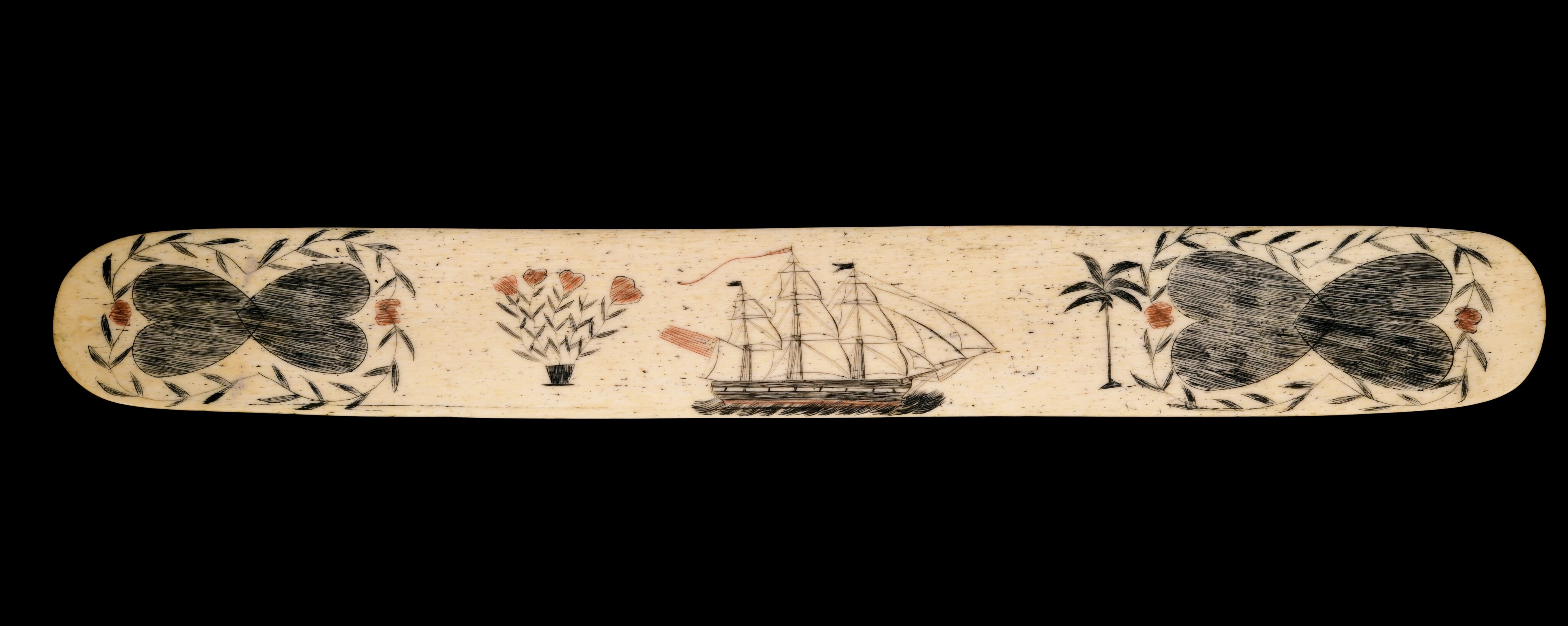

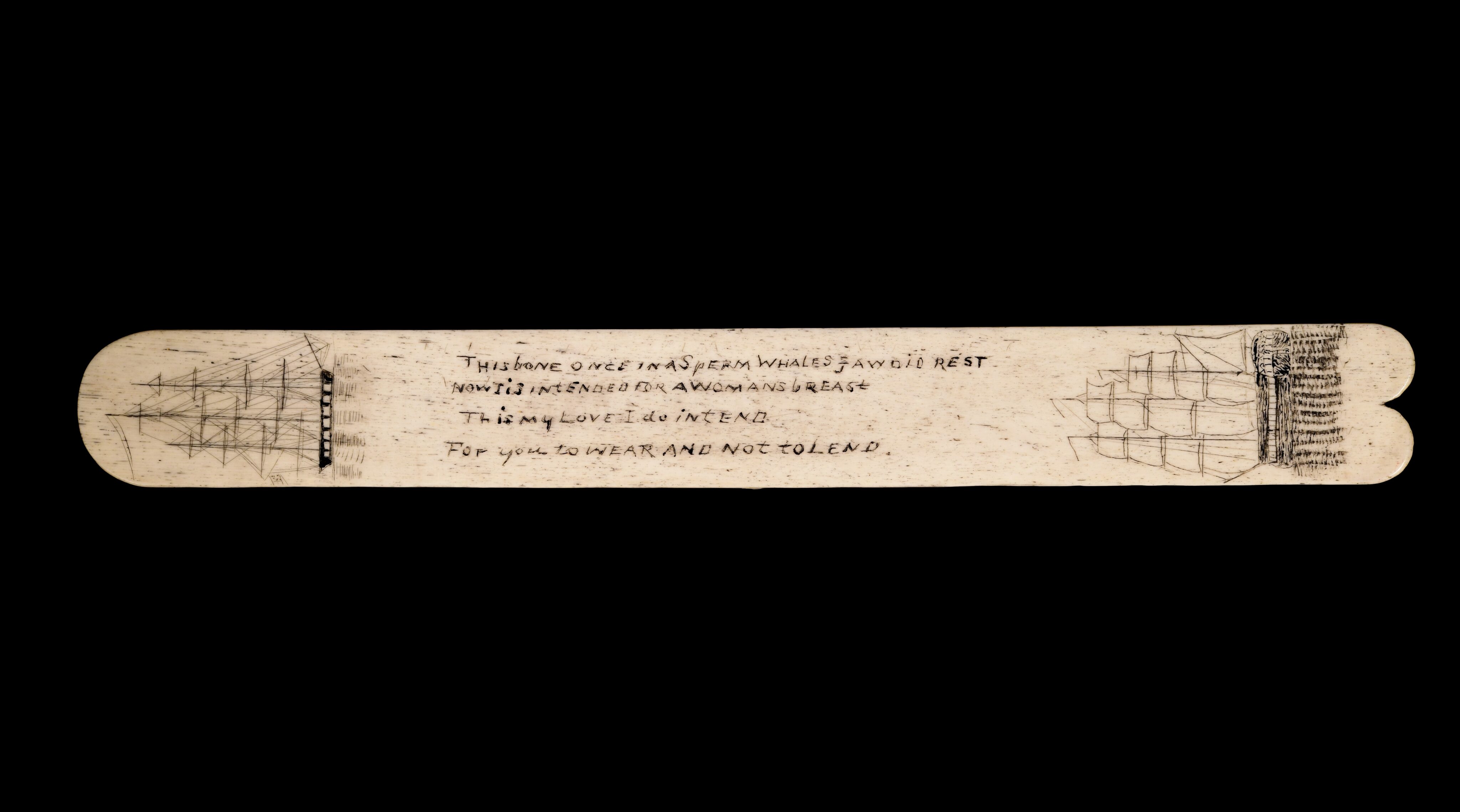

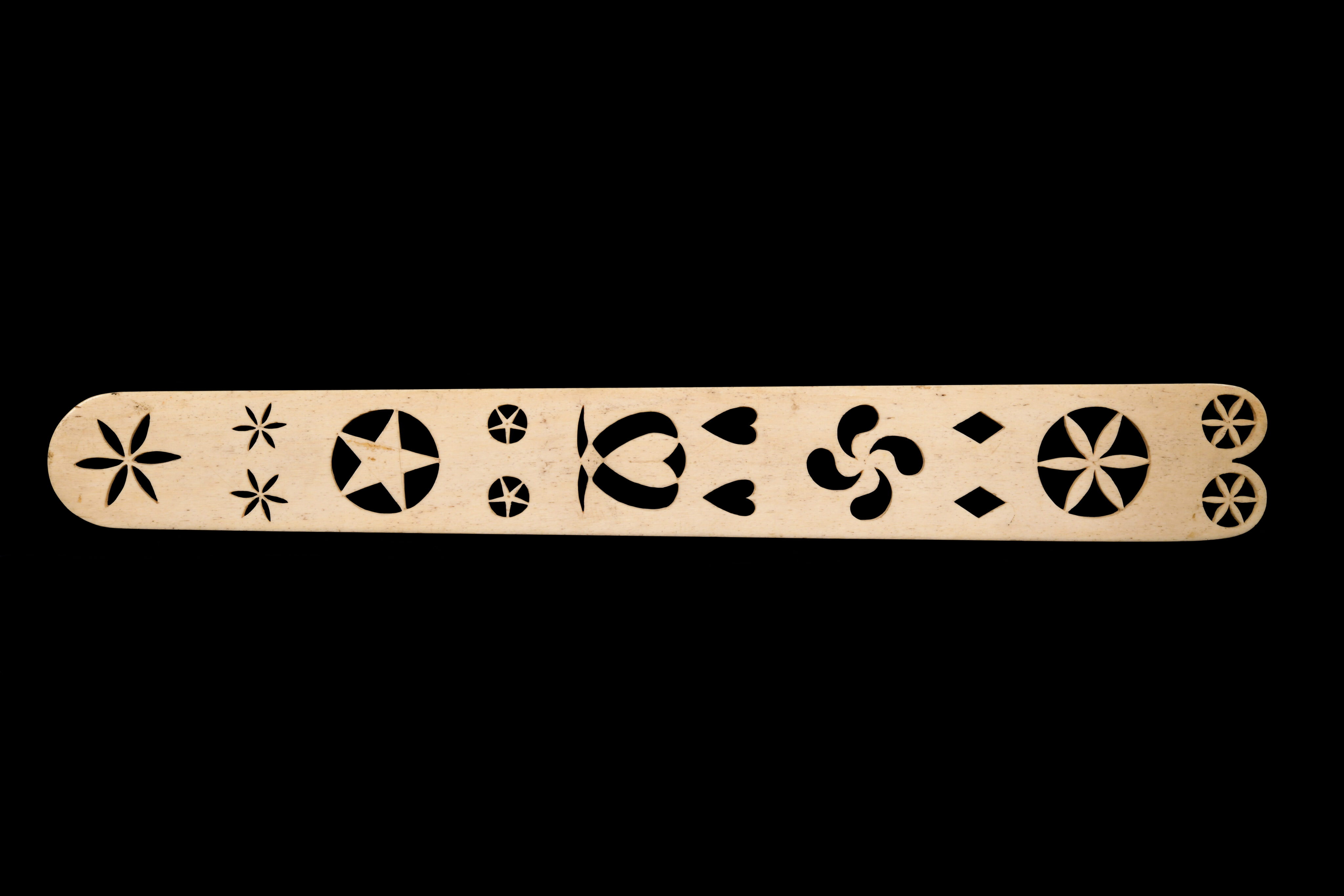

Busks

A busk is an intimate item inserted at the front of a corset to stiffen it. Busks are often carved, decorated, or inscribed with messages, and traditionally given by men to women. Corset busks made from whale panbone, wood, and baleen invite consideration of their maker and user, gender, and the distances of maritime life and domestic longing.

Images of hearts, flowers, and couples suggest romantic love, while Pacific scenes, coconut palms, and ships, eagles, flags, and forts illustrate how US whaling was an imperialist venture. Such motifs speak to life in the Pacific and telegraph desire, longing, and translocation during the long whaling voyage, which lasted on average three to five years.

One busk, known as the palm tree busk, combines domestic imagery with Pacific motifs. An unknown maker pictured a seated woman with a book and cat, a long-necked bird (perhaps a Pacific heron), a palm tree and plant (perhaps flowering ginger), a woman dancing, a full-rigged ship under sail, a dog, an indigenous woman carrying a baby on her back, and a man climbing a fruiting coconut palm. Pacific Islanders served on US whaling vessels and many US whalers had homes in the Pacific, where wives and children lived. Where was home for this unknown maker? Is the scenery imagined or does it refer to real places and people they saw?

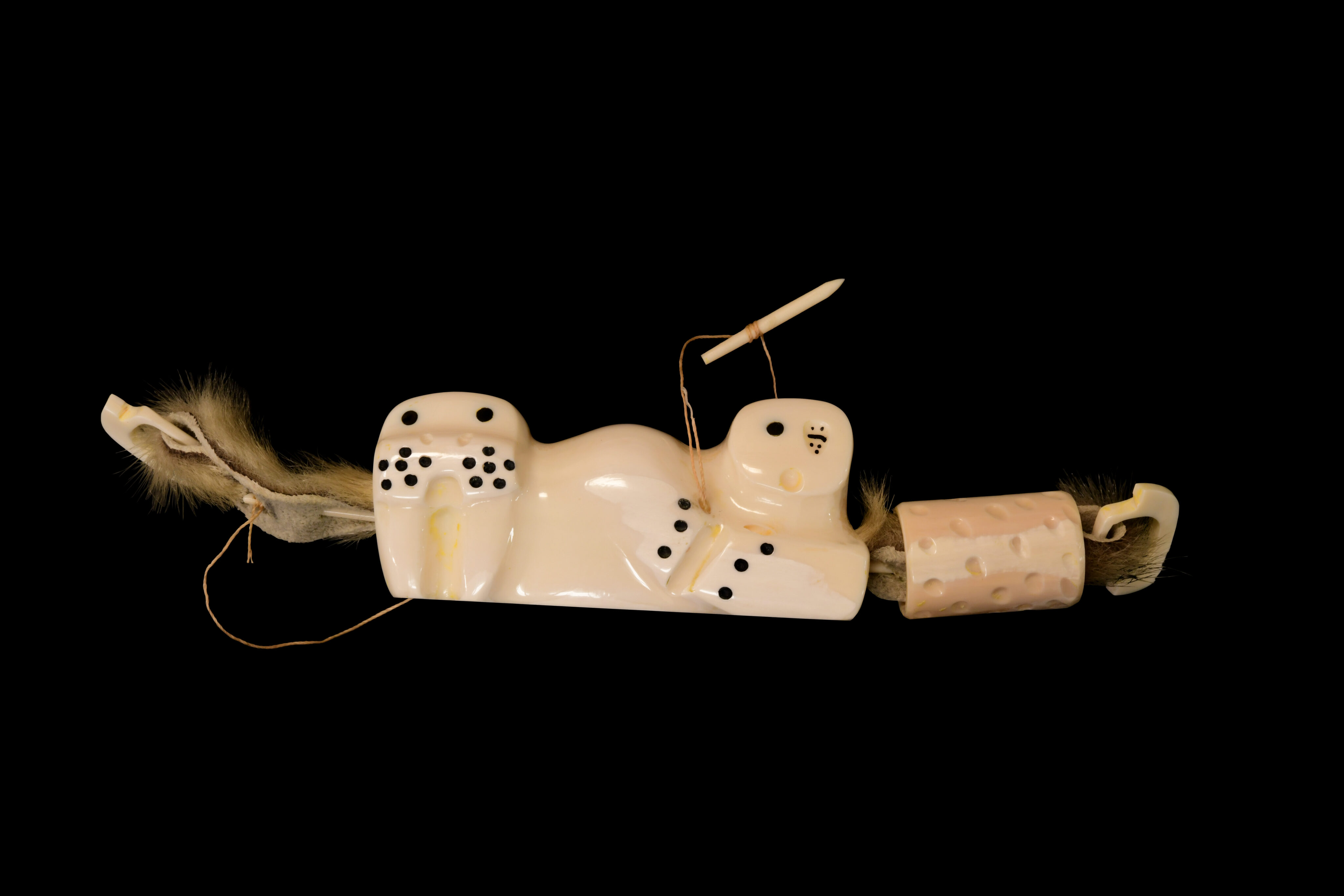

Fids & Needle Cases

Sailors made utilitarian objects, like fids and needle cases, from whalebone for use on shipboard. A fid or rope-working tool was an integral part of any sailor's work kit, along with sail making needles, hooks, marlinespikes, and needles and thread.

One unusual fid likely had at least two makers. Originally fashioned out of skeletal whale bone by a US or English whaleman, this fid was decorated with design elements typical of the Marquesas Islands. This makes it a rare example of cross-cultural hybridization and suggests either a shipboard collaboration between diverse crew members or an island trade.

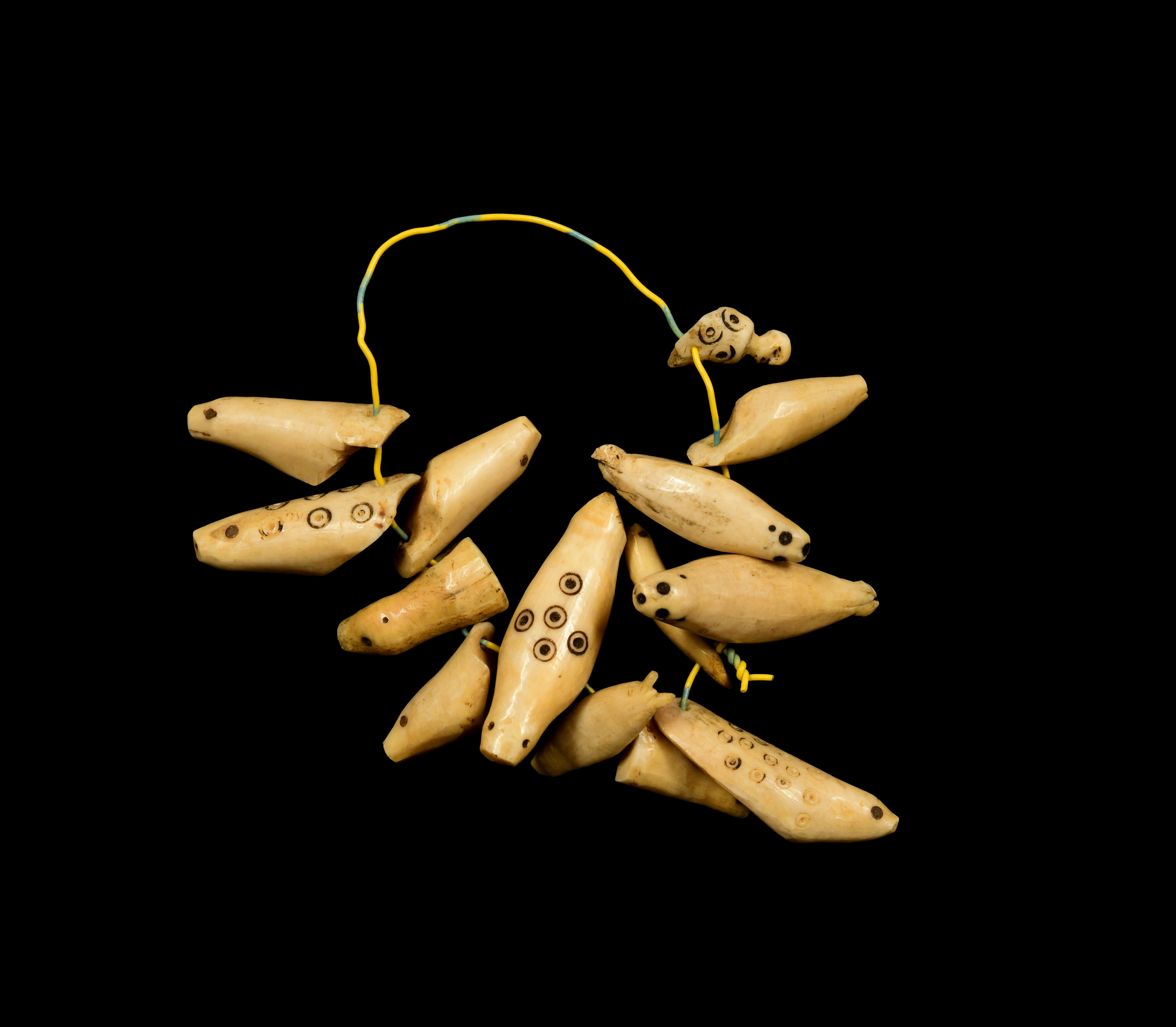

Another popular trade good was the common needle case, a small holder for sewing needles. One example composed of three pieces of walrus ivory to form a seal and a walrus was made by an Iñupiat carver and sold to Captain William Allen around 1905 on the North Slope. Another was crafted from the beak of an albatross, an enormous Pacific bird that spends the first six years of its fifty-year life without ever touching land. Albatrosses are an apt, albeit unintentional, metaphor for a whaler.

Betel Nut Containers

Betel nut is a stimulant and comes from the areca palm, which is grown across the Pacific, Asia, and East Africa. The seed is cut, wrapped in betel leaf, mixed with lime paste and tobacco, and chewed. It was observed as early as 1565 by Spanish mariners in the Solomon Islands. Today its use is contentious but widespread across Oceania.

Exhibitions present a good opportunity to scrutinize the written record of objects in a museum collection. At least four items were recorded as needle cases when, in fact, they are lime flasks used in betel nut consumption. One lime container long catalogued as a needle case shows a volcanic island with two figures. On the other side is a fruiting palm tree, perhaps an areca—the source of the betel nut. This misidentification demonstrates how curators and museum professionals are fallible and affirms that knowledge is best generated in partnership with stakeholder communities and culture bearers.

What Is “Settler Colonialism”?

Settler colonialism is an ongoing system of power that perpetuates the repression and genocide of indigenous people and cultures. It normalizes the occupation and exploitation of land and resources to which Indigenous people have genealogical relationships. It includes interlocking forms of oppression, like racism, white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, and capitalism. While traditional colonialism is similar, settler colonialism focuses specifically on the removal of Indigenous people from their historical lands.

Whalers, merchants, and missionaries participated in colonizing the Pacific world. As individuals, they facilitated settler colonialism in these regions. They might not, however, always have been aware of the role they played. Systems of power, like settler colonialism, are much more complex than one person or instance. They also continue into the present in myriad ways.

Jerome Saclamana: Iñupiaq Artist, 2019. Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, Alaska Office, Anchorage Museum, Courtesy of the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center.

Gender & Sexuality

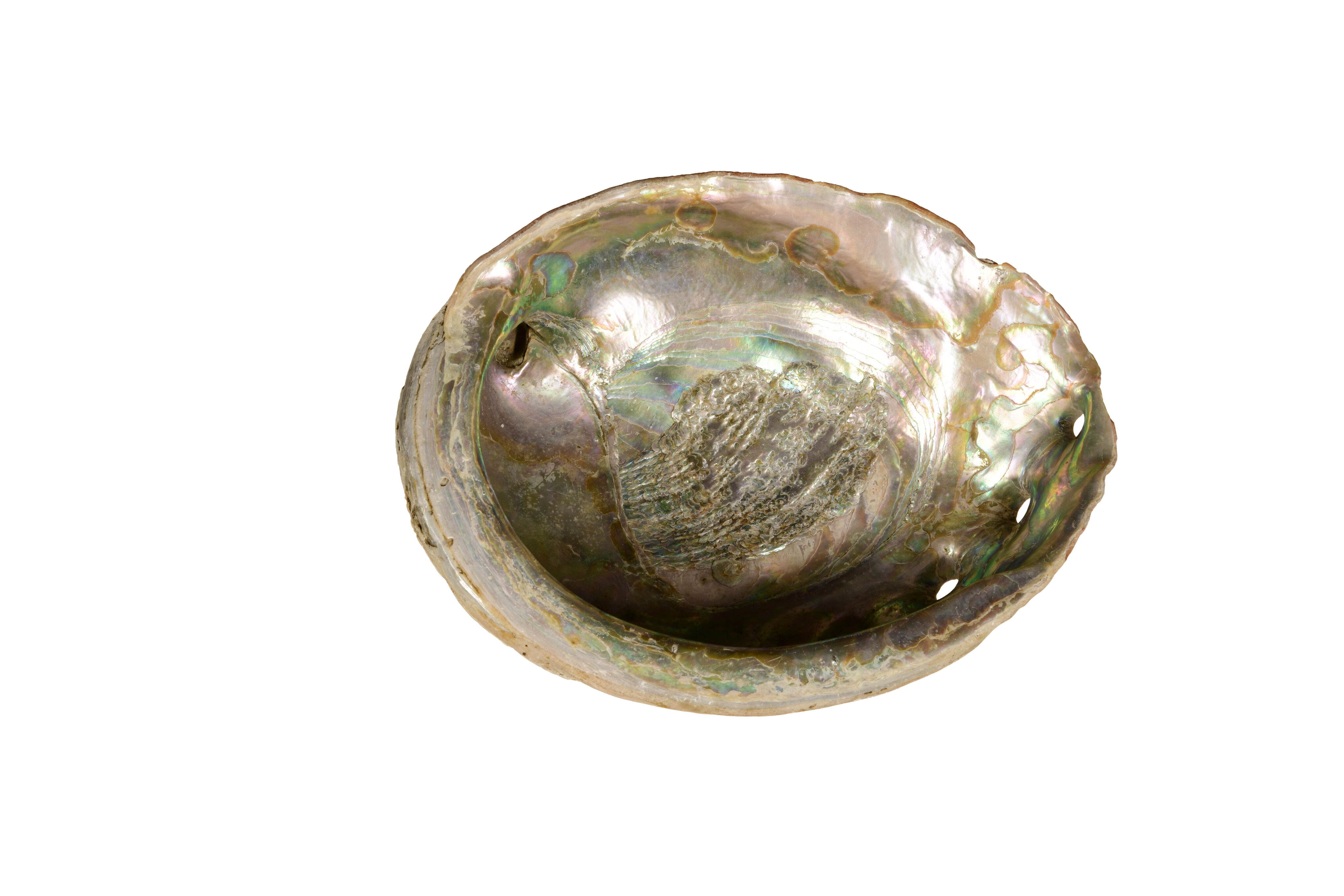

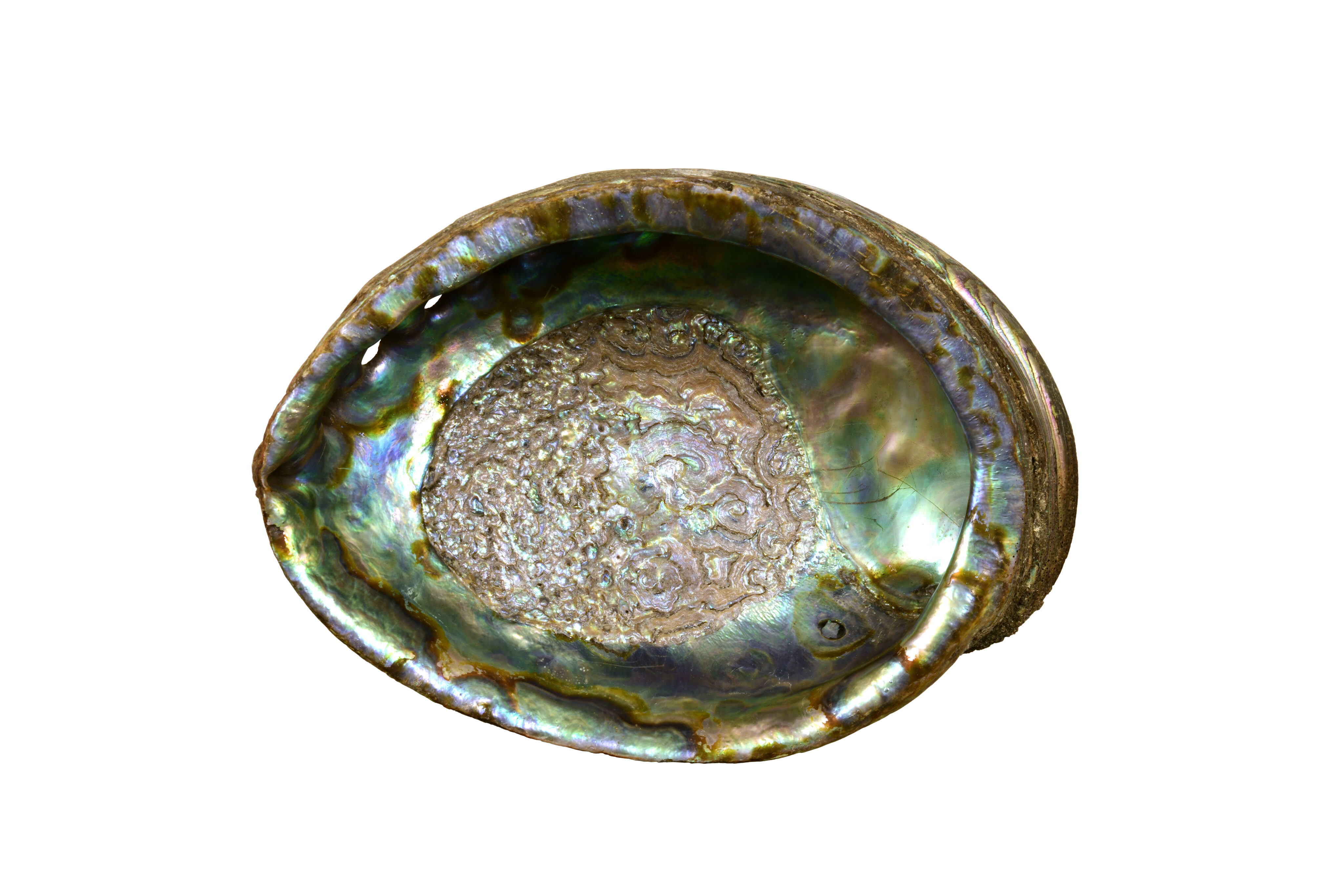

Sailors made domestic objects as gifts for their mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters, or for trade or sale. Jagging wheels or crimpers were designed to run around the perimeter of a pie before it went into the oven to bake. They sealed the edges of the crust against the pan or bottom crust and held in steam heat for better, more even cooking. They could be made in any shape and often include materials acquired at sea, like abalone, ebony, tortoise shell, and the bones, teeth, and baleen of marine mammals.

These artifacts supported the domestic comforts of home and labor mostly embodied by women. Such items could take hundreds of hours to make and are a reminder of the purpose of scrimshaw: to fill the time, keep hands busy, and ease boredom. The manufacture of such objects also suggests how absent women, their bodies, and the intimacy of physical connection, occupied an imaginary space on shipboard. A small group of pie crimpers and engraved whale teeth picture erotic or domestic scenes and invite visitors to imagine what physical separation meant for whalers and their wives or partners.

Wahinee Teeth

Teeth that show a wahinee, a Hawaiian or “exoticized” Pacific Island woman, indicate a more illicit maritime trade. The Native woman is topless and dressed only in a skirt. She is unselfconscious and outside underneath fruiting palm trees. This is starkly contrasted with a Victorian parlor on the back. A fully dressed Euro-American woman sits at a table within a comfortable domestic interior.

The fetishization of Indigenous women and girls is a continued aspect of colonial domination. Explorers, missionaries, and whalers as far back as the 1760s sexualized Pacific women. They viewed Indigenous women as sexually available due to their different clothing. In some cases, sexual relations facilitated trade or were due to imbalanced power relations or different cultural ideas about sex. Stereotypes about available Pacific women as “available” facilitated a sexual imaginary about the Pacific and Native women more generally. Venereal diseases were one outcome, sexual violence another. Native and Pacific Islander women are still exoticized and othered in mainstream media and popular culture. They are also sexually assaulted two and a half times more often than non-Native women. It is important to name this historical and ongoing harm.

Coconut dippers & vessels

Coconuts were a trade good from India and the Pacific, introduced to the Caribbean and Americas around 1500. In the 1800s, coconut dippers were ubiquitous across the United States, where they were used for communal water drinking in domestic and industrial settings.

Dippers were simple: half a coconut shell attached to a handle. Their construction and materials varied widely. Dippers in this section are made from coconut, walrus, whale, and elephant ivory, whalebone, abalone, tortoiseshell, rare woods, baleen, copper, and silver. Made by whalers, sailors, Iñupiaq, and Pacific Islanders, dippers illuminate global histories of colonialism, maritime trade, and imperialist projects. They vividly showcase the global circulation of natural materials in the 1800s.

More generally, vessels made from wood, gourds, and carved coconut shells are a form with diverse histories and uses. They bring people and materials together in unique, culturally specific ways. Items were created by individuals from the Marquesas, Hawaiʻi, and the Solomon Islands for communal drinking, feasting, and ceremonies. Sharing of food, offering a drink, coming together, these acts forge communities.

Building Empire: Pacific Worlds

A pitcher made in England around 1800 demonstrates how imperialist agendas and empire building became mainstream in the early United States. On one side, George Washington steps on a lion representing England. A banner reads: “By virtue and valour, we have freed our country, extended our commerce, and laid the foundation of a great empire.” On the other side, a map of the eastern half of North America is flanked by triumphant figures. Designed for US consumers, the images and text celebrate conquest, territorial expansion, and economic progress built on the exploitation of global natural resources. They visualize the nascent nation’s imperialist ambitions.

What Is “Imperialism”?

Imperialism is the practice of extending power and dominion of one nation over another area through territorial acquisition or by gaining control over politics, culture, or economic resources. Today, approximately 2.3 million people live across the Pacific Islands, over half of them in US-affiliated territories like American Samoa and Guam.

The Coconut as Cosmology

Ni (coconut tree) is essential to the economies and cultures of Moana Oceania. It is called the “tree of life,” “tree of heaven,” and “tree of abundance,” and every part has a use. The nut can be eaten, carved, pressed into oil, scraped for cream, or used as a vessel or as fuel. The husks become coir for ropes and mats, or sennit for twine. The water is drunk or processed into milk. The leaves become roof thatch or baskets. The trunk is for building. The sap is fermented into wine. The juice creates sugar.

Numerous Pacific communities have stories about the coconut. One from Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ (the Marshall Islands) describes its origin. Limokare births a son Debolar, the first coconut, nurses him on her milk, and plants him in the ground, where he provides for all. A creation story from Mangaia (Kūki ‘Airani/Cook Islands) describes how before time the universe was a hollow coconut with layers for different spiritual realms. At its base a woman, The-very-beginning, generates the first humans out of loneliness: Tangaroa and Rongo.

Coconuts float long distances and will still be viable. Landing on a new shore after a hundred days at sea, a coconut will grow into a tree. Because of this, the coconut is framed as an apt metaphor for the adaptability of Pacific communities, who journeyed between island chains for millennia. The Pacific diaspora changed in the 1800s, as imperialism and colonialism impacted island nations in different ways. US and European militarism (including testing and defense), foreign investment, corporate interests, and environmental degradation negatively impacted many island communities. Today, climate change is the largest threat to the region.

Pacific natural resources—such as coconuts and whales—, drew explorers and colonizers, who exploited plant and animal resources for financial gain. Owing to this, almost the whole of Oceania passed under the control of European powers and the United States between 1842 and 1900. Today, largely for strategic and economic reasons and despite UN support for self-determination after 1945, the Pacific has still not been completely decolonized.

Containers & Baskets

Work baskets, storage containers, and sewing or ditty boxes accommodate personal belongings like needles, thread, and soap. Some were made by Pacific Islander, Azorean, and New England whalers on shipboard, others were crafted by Iñupiat, Makah, and Native Arctic makers. The diverse materials used in their construction include whale or walrus ivory, panbone, baleen, cedar wood, abalone, mother-of-pearl, tropical hardwoods, ebony, tortoise shell, grasses, and in one case African porcupine quills. Some are inlaid with whimsical decorations, carved, or fancifully incised. Others are made of pierced fret or latticework. These varied containers demonstrate a transoceanic exchange of forms and materials during periods of intense pressure and adaptation.

Born in 1821 in Tisbury, Martha’s Vineyard, William Cottle traveled on at least six whaling voyages to the Pacific in the 1840s to 1850s. The first returned with forty-three thousand pounds of whalebone (baleen). Baleen was the plastic of the 1800s, used in everything from corset stays to parasol ribs. This unique ditty box sheathed in baleen is incised with a scene from the War of 1812. While pursuing armed British whaling vessels in the South Pacific, Commodore David Perry stopped at Nuka Hiva in the Marquesas Islands and got involved in a tribal war. Cottle pictures Perry burning the Greenwich upon retreat. The unusual addition of color vividly brings the inferno to life, solemnly observed by a Nuka Hiva Islander from land. Why did Cottle choose this scene to picture? And what led him to present it from the Islander’s perspective sitting on the shore?

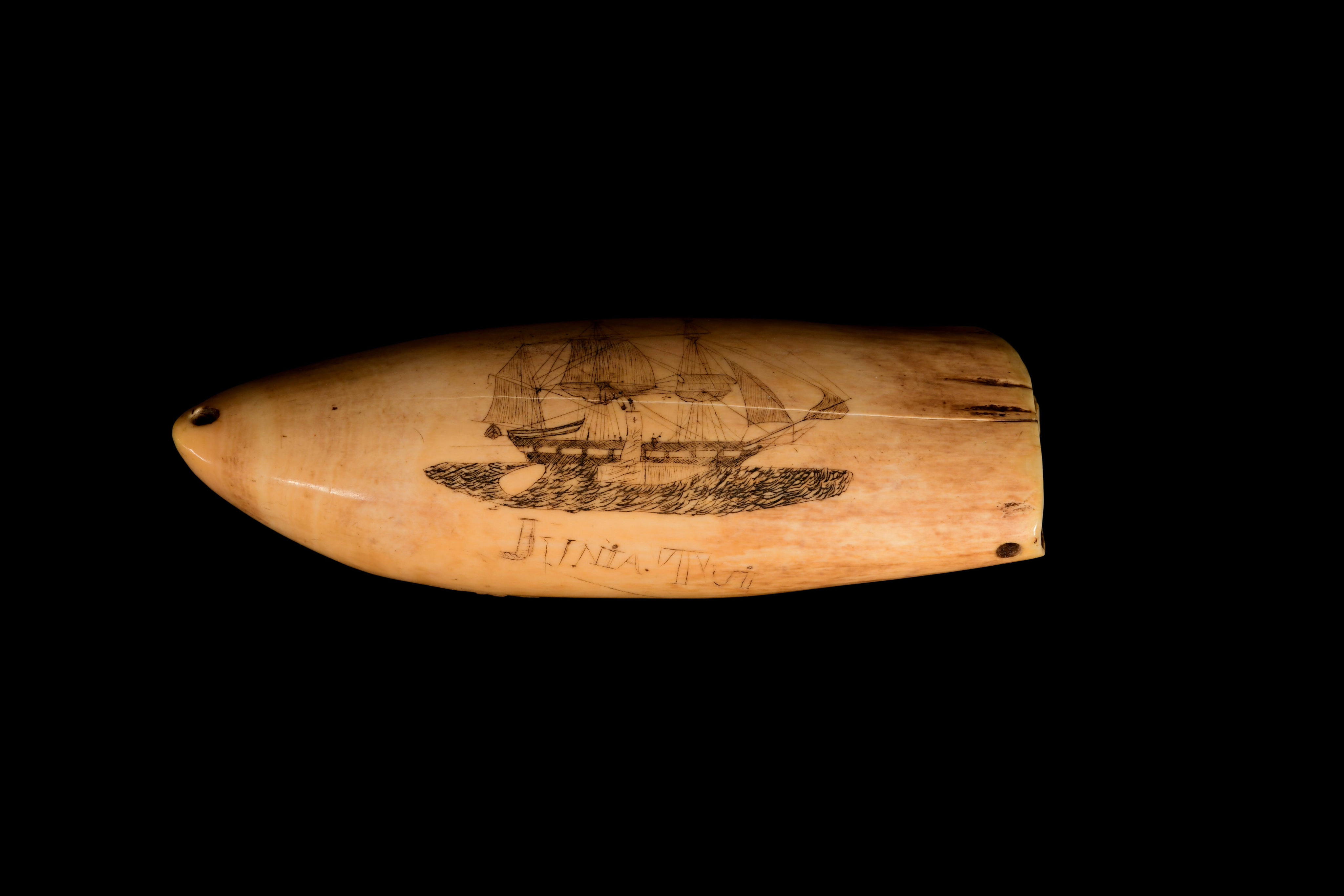

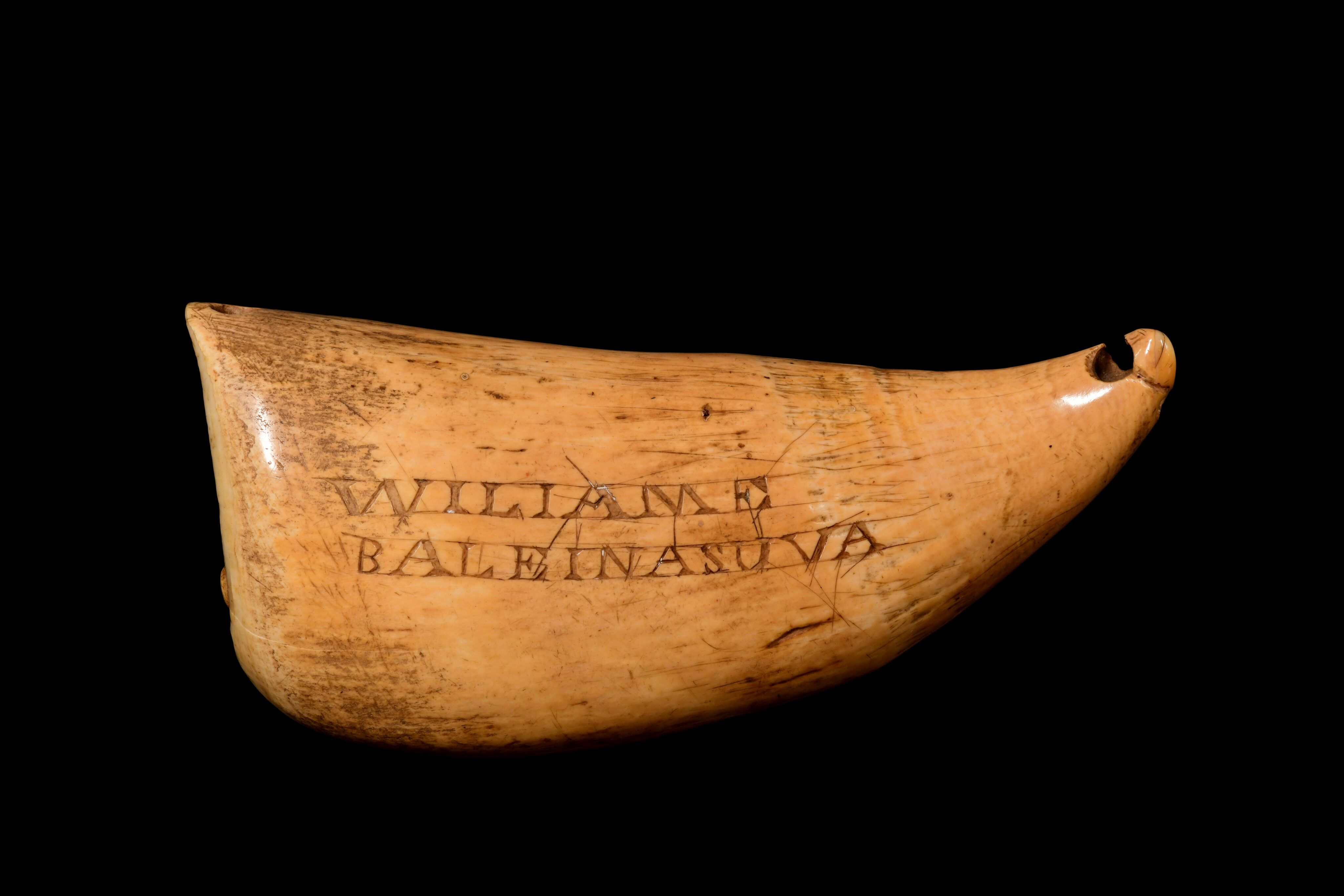

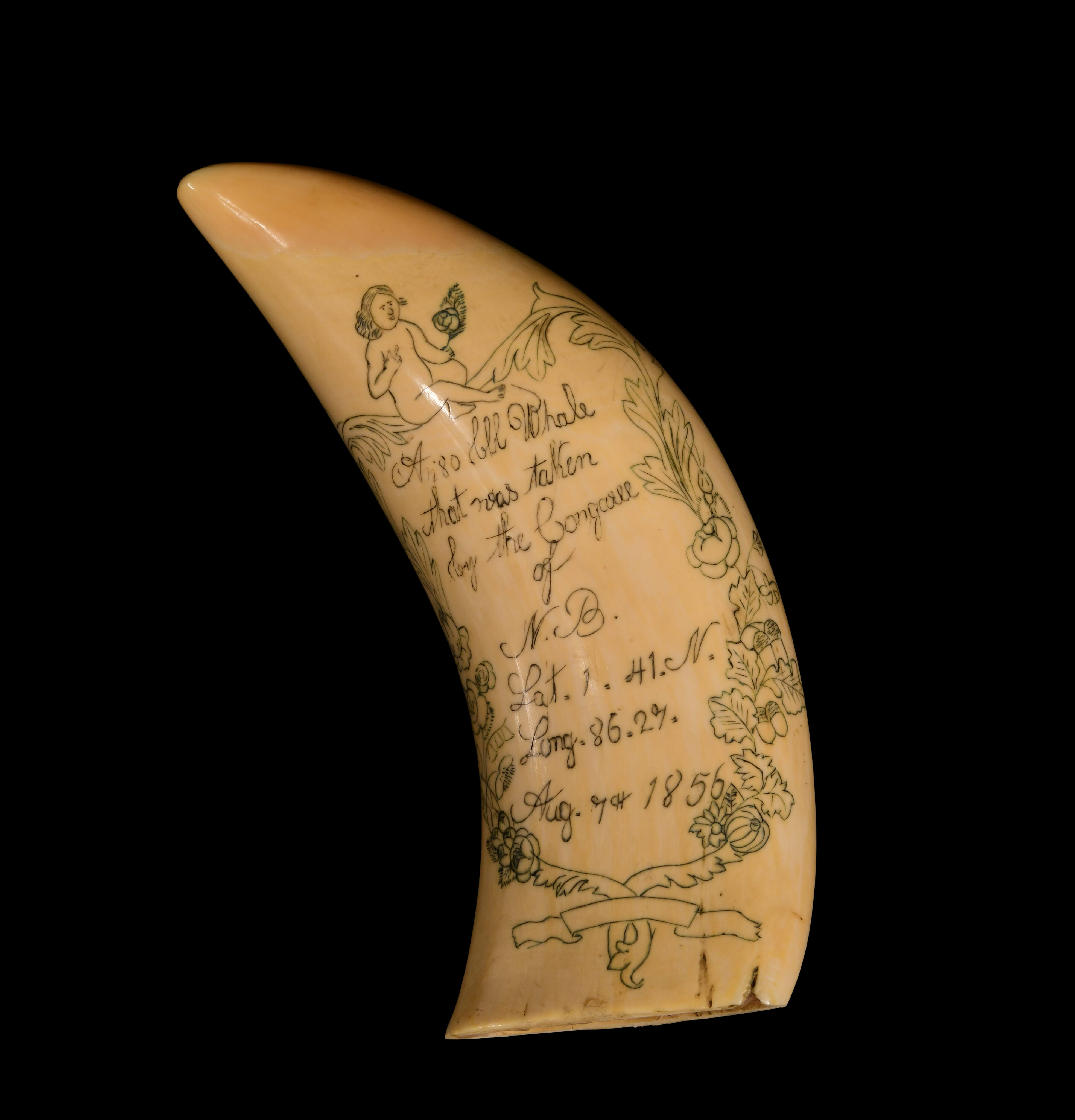

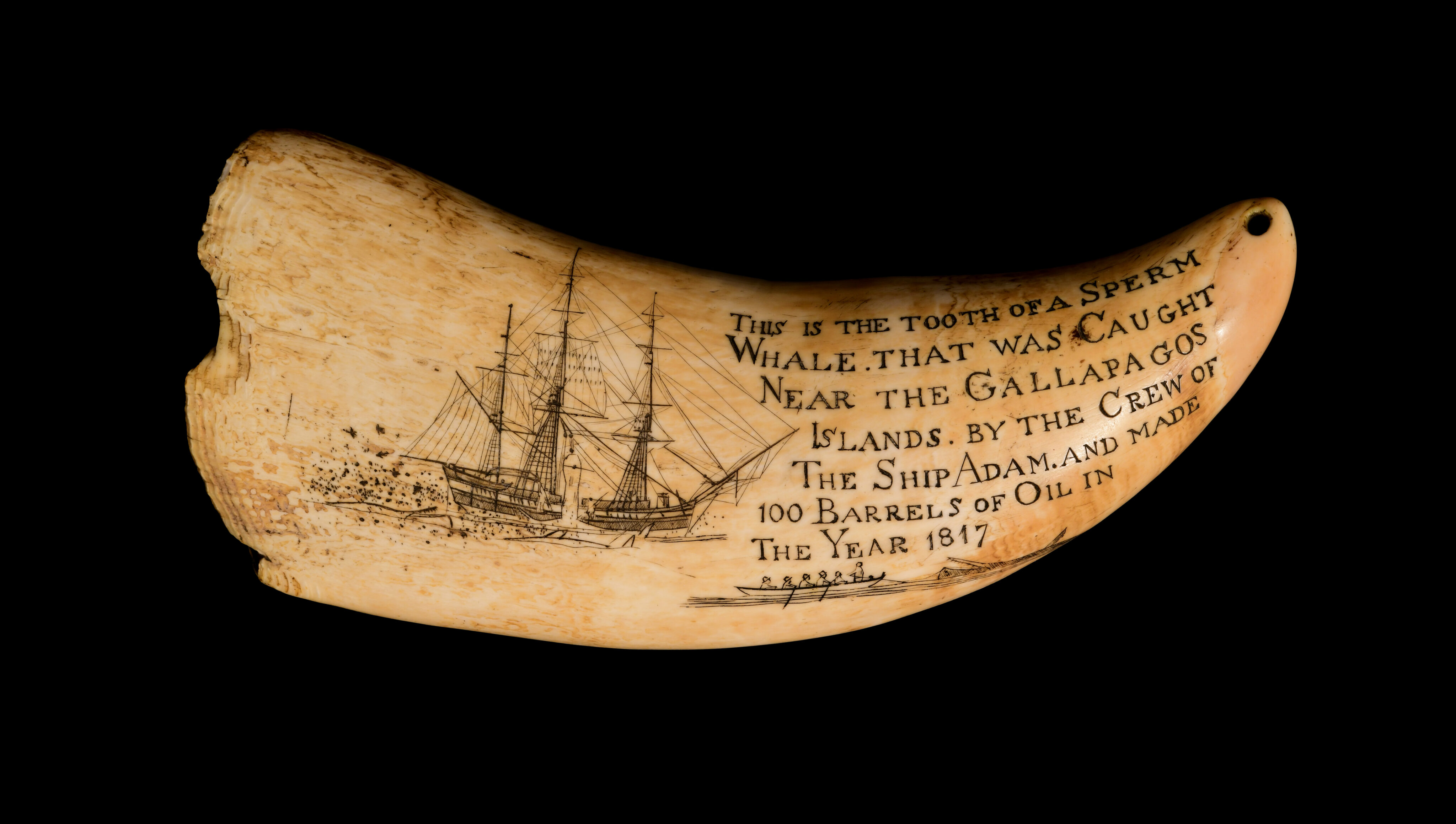

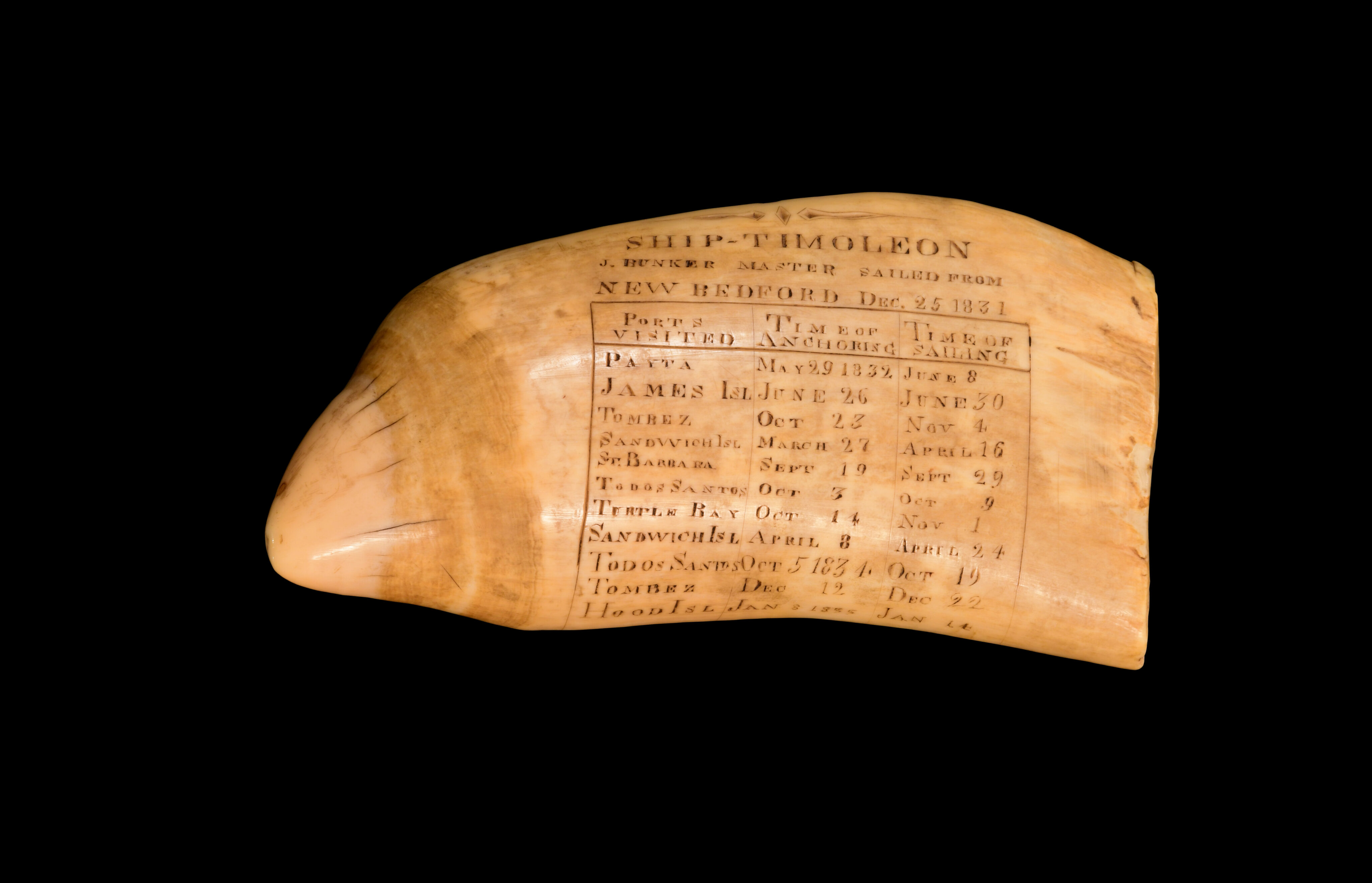

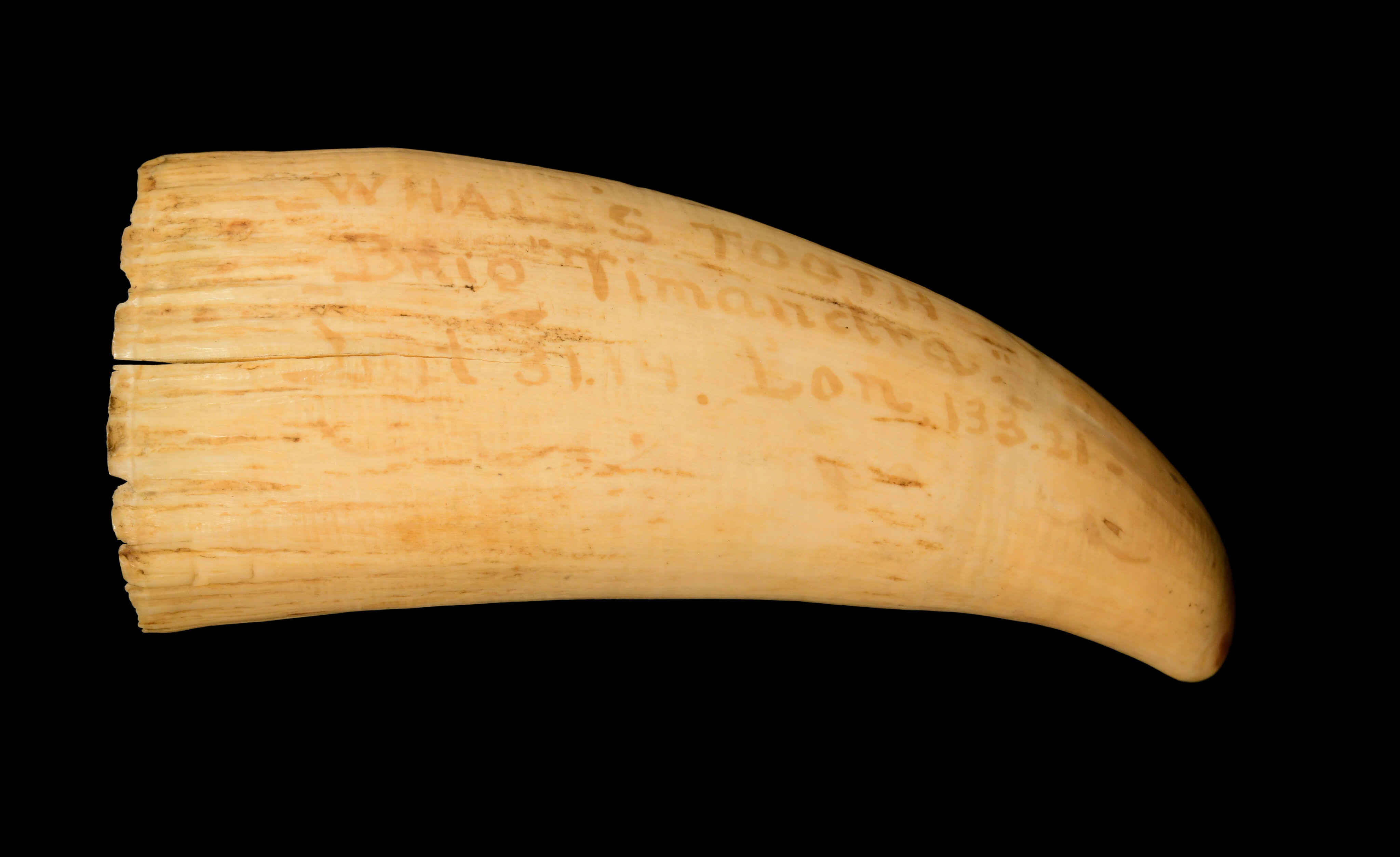

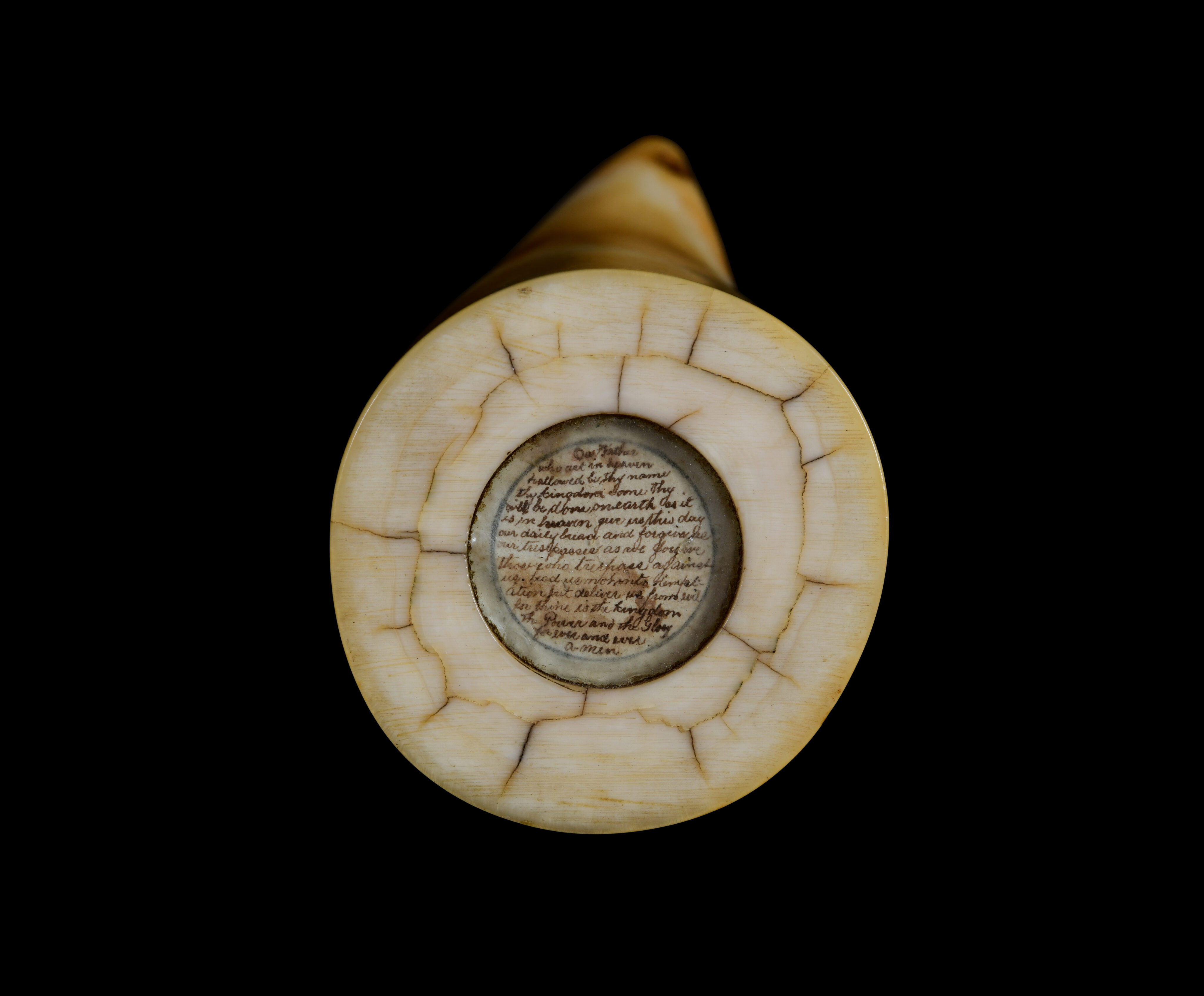

Engraved Whale Teeth

Sperm whales have about forty-six teeth, which were prized for scrimshaw. After being extracted from the whale’s mouth, the teeth were scraped smooth and polished. Crewmen kept, traded, or decorated them as personal souvenirs or for the mass market. They made designs freehand or with a template. Some artists copied popular visual culture from magazines, while others pictured what they saw at sea. Engraved whale teeth are considered an iconic scrimshander’s artform and the pinnacle of whaling art.

In this section, twenty-five teeth made by documented Black, Cape Verdean, Azorean, New England, Māori, and Australian Aboriginal makers depict Arctic or Pacific Island landscapes. Some identify where the whale was taken, as in “near the Galapagos” or “near Juan Fernandez.” One records the successful capture of a sperm whale on January 7, 1836, off the coast of Aotearoa by a whaleman from Wiscasset, Maine.

Some teeth had multiple owners and were used as tabua, highly prized items in Fijian society. One tabua demonstrates the syncretism of traditional Fijian beliefs with Christianity—inscribed on its base is the Lord’s Prayer. Still others adopt traditional Māori Tā moko markings, reproduce Sydney Parkinson's A New Zealand Chief engraving after an illustration from the first Captain Cook voyage, or show views of Huahine or Honolulu. Taken together, these teeth demonstrate how whalers traveled across the Pacific and highlight individual exploits or identities.

The “Dream Tooth” was likely executed by an Australian Aboriginal whaler, perhaps from Eden, an area on the South Coast of New South Wales. Whaling ships operated around Eden starting in 1791, and the first shore whaling venture founded in 1828 employed local Thawa Aboriginal people. The tooth pictures six men sailing a proa (boat). One wields a harpoon. A sperm whale lurks beneath. On the other side, a man stands aloft with a boomerang in flight. The outlines are distinctively patterned, akin to Australian Aboriginal dreamtime images.

Whaling crew lists record hundreds of names of men born in the Pacific, from New South Wales, Tasmania, New Zealand, and Peru, to Guam, Chile, Tahiti, the Sandwich Islands, and Australia. These individuals are almost all described as dark, black, or brown. Whaleships were interesting spaces. While not without the racism that defined the Euro-American worldview, they required order and followed a strict hierarchy, and ability was rewarded. No matter his color, a skilled man could get ahead on the right whaleship.

The Sea is not Empty, 2021. Wunungu Awara: Animating Indigenous Knowledges, Courtesy of Monash University Indigenous Studies Centre.

This animation was created using stories and songs told by Marra elders in the 1980s. They are Roy Hammer, Henry Juluba, Musso Harvey, Mack Reilly, Tommy Reilly, Ginger Reilly, Emily Wirdiwirdinya, Fannie Gathawuy Numamurdirdi, Tom Simon, and Yanuywa elder Old Tim Timothy.

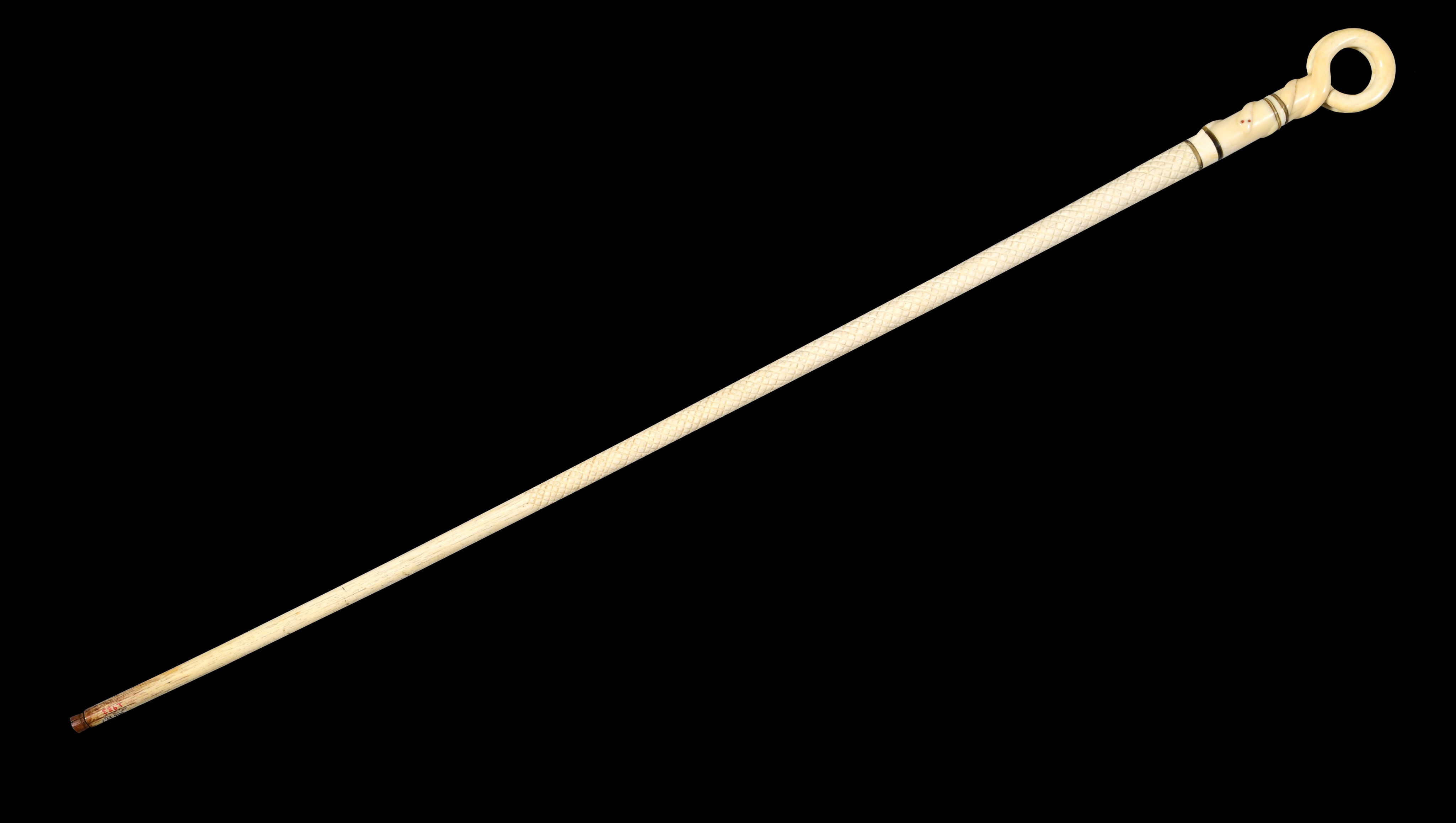

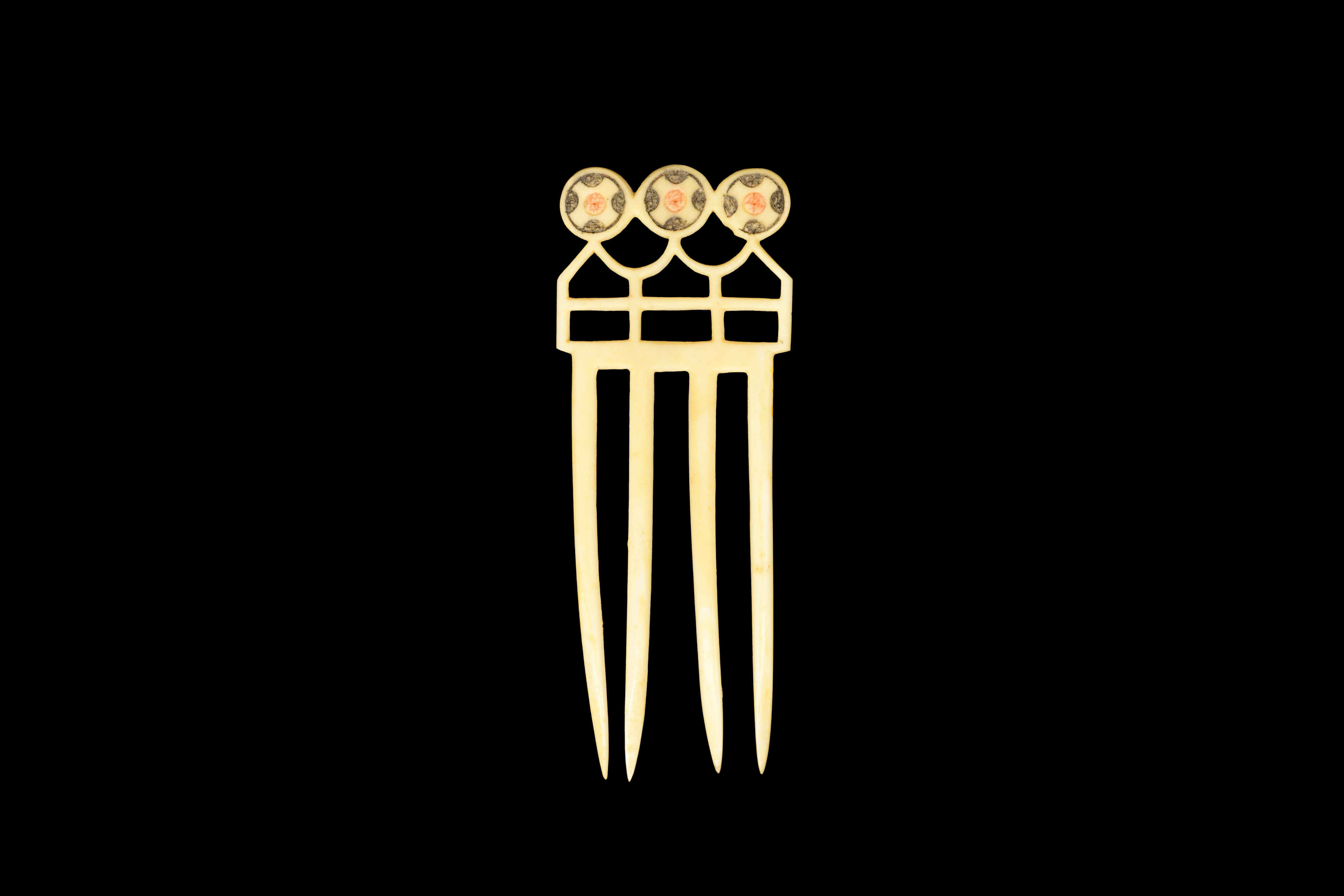

Personal Ornament

Human hair, fiber cords, ambergris, and materials like whalebone and whale ivory were used across the Pacific, Arctic, and United States to create important objects of commemoration, ritual, status, and adornment. Whalemen made elaborate canes from narwhal tusk and whale ivory. One is carved with a stylized mo‘ai, echoing the famed heads of Rapa Nui (Easter Island). These objects illustrate how materials from animal bodies (hair or ivory) held spiritual significance for different cultures, marking important events or individuals and connecting the earthly and divine.

In the 1800s, American women practiced hairwork, weaving, knotting, and braiding human hair into elaborate wreaths, garlands, and jewelry. Often made using the hair of loved ones, sometimes those who died, this commemorative practice was widespread and underlaid with religious beliefs about the body, mourning, and the tangible remnants of the spirit.

Likewise, items of whale ivory, such as Marquesan hakakai (ear ornaments), Fijian waseisei, and Marshall Islands marremarre lagela, demonstrate potent links between the divine and human realm and mark chiefly status. Whales are understood throughout Oceania as manifestations of the ocean god Tangaloa (Tahiti: Taʻaroa; Hawaiʻi: Kanaloa). Whalebone and ivory are sacred and infused with the god’s divine essence. Expertly fashioned into elaborate breastplates, necklaces, and ear ornaments, this rare material reinforced a chief’s lineage and legitimated their rule.

Whale Cosmologies

Whale people are communities who are closely connected to whales through ancestral kinship relationships. Often oral stories about whales are passed down through the generations. Located at the spatial and theoretical heart of the exhibition, this section underscores the import of marine mammals for diverse cultural groups across the Pacific world.

Work by contemporary artists, storytelling, and cultural belongings, such as a Chumash whale carving, a Makah or Nuu-chah-nulth thunderbird head war club made of whale panbone, a Makah harpoon point, a Māori kotiate parāoa, and a Tlingit whale vertebra mortar, underscore the interconnectedness of whales to the lifeways and cosmologies of Native communities.

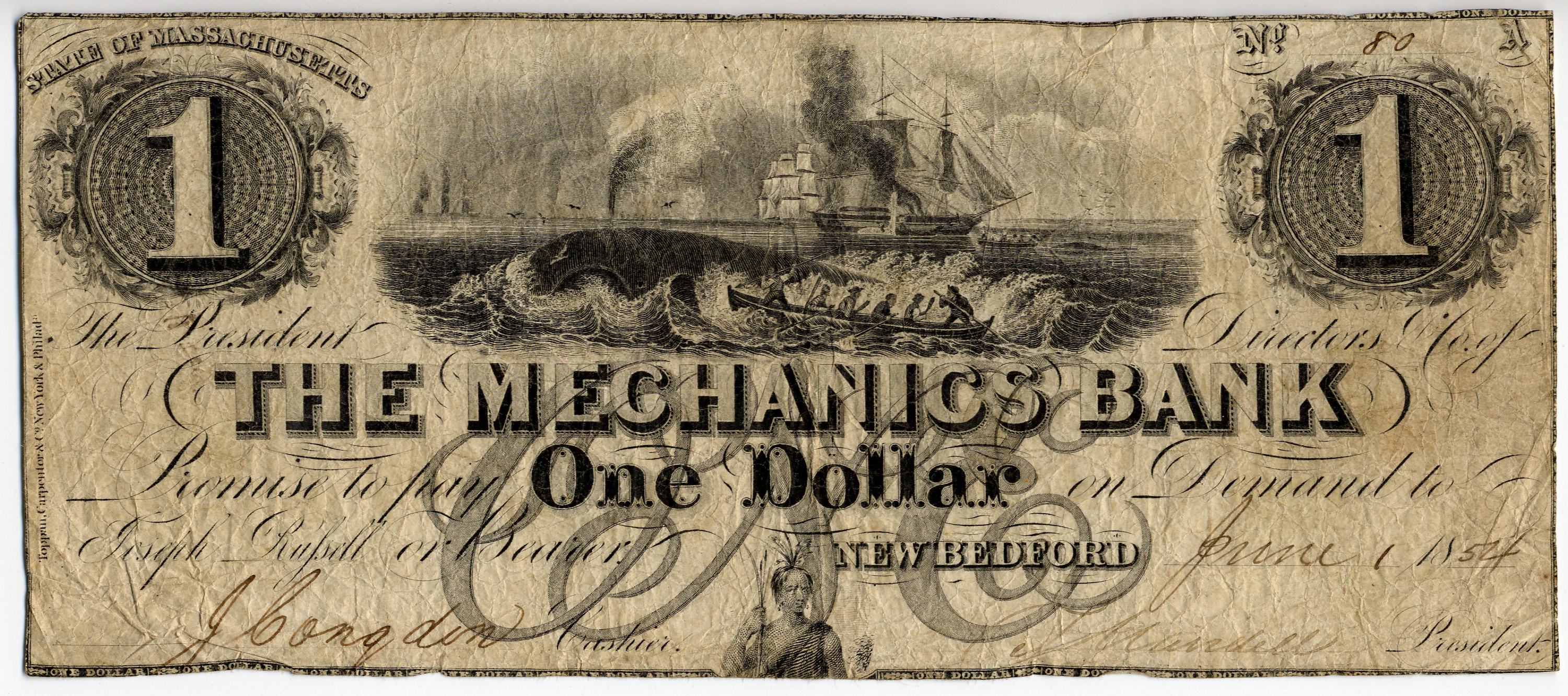

These items demonstrate how whales remain part of Indigenous life in the Pacific world. They also evoke the presence of thousands of whale ancestors. A bottle of whale oil and a US banknote present a juxtaposition between ongoing sustained relationships built over generations between Native people and whales and US whalers’ economic motivations.

LISTENING FOR BOWHEADS

an interview with Gordon Brower, Iñupiat whaleboat captain

Ame Papatsie, Qalupalik, 2010. Nunavut Animation Lab, National Film Board of Canada.

This animated short tells the story of Qalupalik, a part-human sea monster that lives deep in the Arctic Ocean and preys on children who do not listen to their parents or elders. That is the fate of Angutii, a young boy who refuses to help out in his family's camp, opting instead to play by the shoreline. But one day, Qalupalik seizes him and drags him away. Angutii's father, a great hunter, must then embark on a lengthy kayak journey to try and bring his son home.

Totem poles

Two North American Indigenous carvings emphasize the connections between humans and animals within a shared ecosystem. A whale bone carved into stacked animal forms inlaid with abalone was likely made by Atlieu (Charlie Williams), a Nuu-cha-nulth/Makah carver in the 1890s. Around the same time, a Tlingit or Haida carver depicted a raven between two seated bears on a whale panbone.

These are set in conversation with examples created as trade goods by Native artisans or ones made to simulate Native artistry. One carved on hippopotamus tooth, replicates the Kiks.adi (Kiksett) Totem, a second looks like Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw work. Another may have been commissioned from a Native carver and carries the label of the Hudson’s Bay Fur Company, whose history with Indigenous communities is highly complex. Such examples demonstrate the cultural violence perpetuated by non-Native entities as the market for Native-made goods intensified. The popularity of collecting Native and non- Native carvings arose in the 1920s concurrent with the adoption of increasingly aggressive assimilation policies in the United States and Canada that caused significant harm to Native communities.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) is a human rights law enacted in 1990. It provides for the protection and return of Native American human remains, funerary objects, and items of cultural patrimony. By enacting NAGPRA, Congress recognized that Native people "must at all times be treated with dignity and respect" and human remains and cultural items removed from tribal lands belong to lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations. Museums must provide comprehensive inventories of all Native American human remains and funerary objects and summaries of cultural items in their collection to Native groups. NAGPRA expressly assumes that museums should not be making any determination about whether Native items in a museum’s collection are culturally significant or how to best care for, interpret, and exhibit those items. It understands that tribes have the right and cultural knowledge to ascertain what is important to them and what should be done with their cultural artifacts. The spirit of NAGPRA is to ensure Native people have a right to self-determination about the treatment and exhibition of their cultural heritage and ancestral remains.

The Kiks.adi (Kiksett) Totem

ISHMAEL ANGALUUK HOPE, Tlingit and Iñupiaq poet

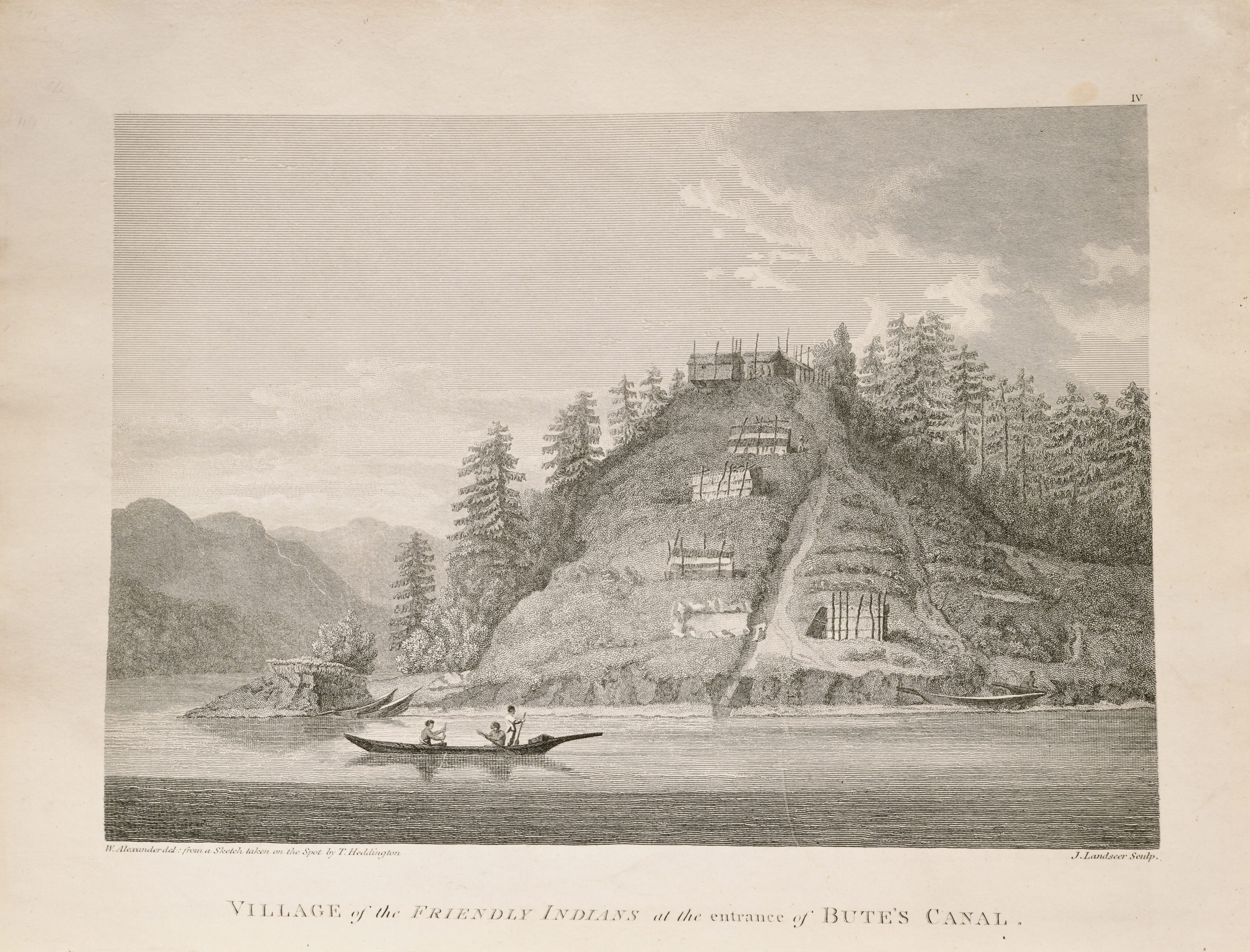

Trade Goods

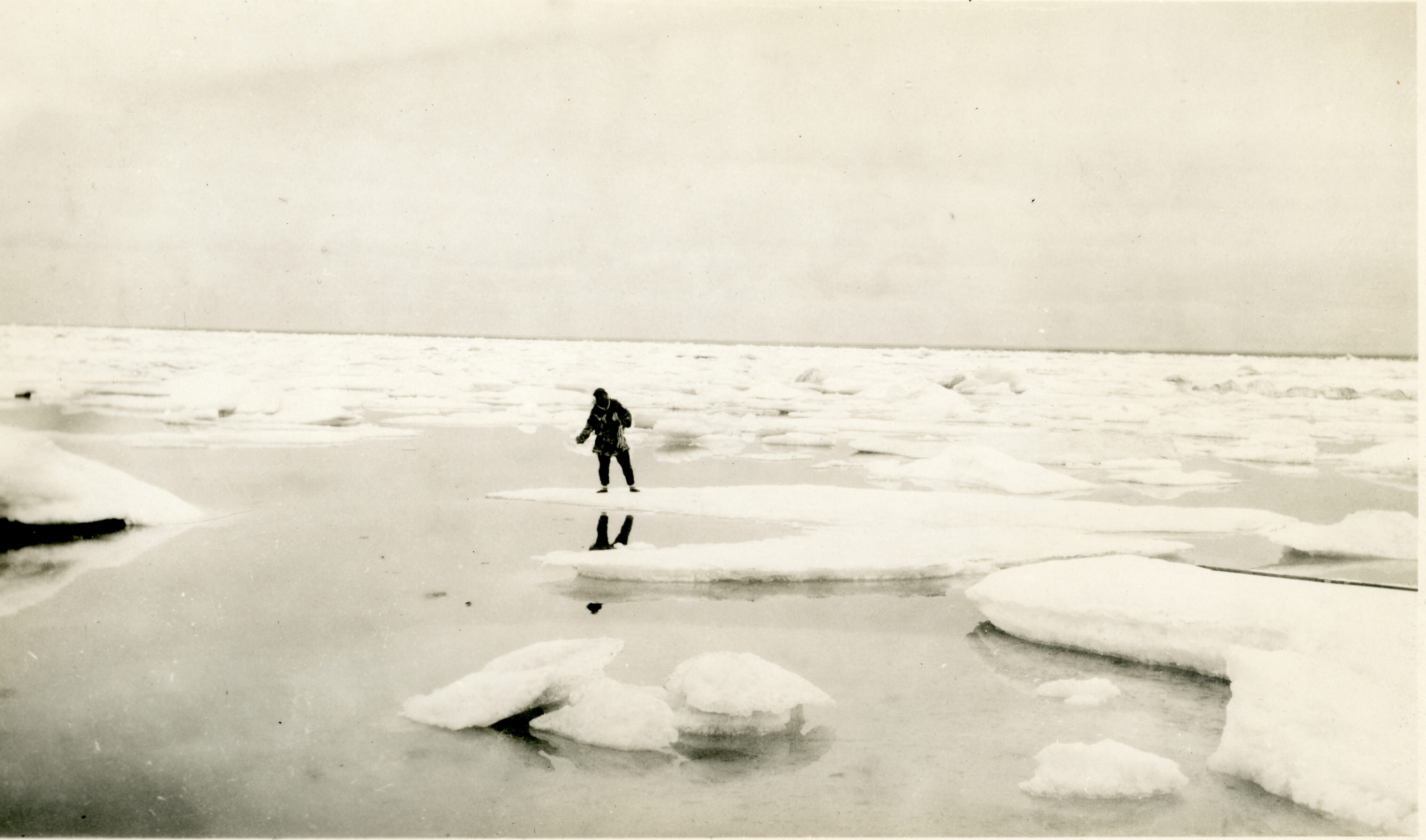

An active carving tradition developed in the Pacific Northwest and Arctic regions for internal cultural and spiritual use. This was adapted in the early 1800s for outside markets through trade and later tourism. The fur trade (especially sea otter and beaver pelts) and explorers like Vancouver and Cook spurred contact between settlers and Native communities in the Pacific Northwest. Over two hundred vessels visited between 1785 and 1804 to trade, mainly for blankets and firearms. The near extinction of sea otters drove the trade inland, promoting Euro-American settlement and resource extraction. Similarly, outside explorers and fur traders arrived in Alaska in 1741, and the first settlement was in 1784. In 1867, the United States purchased Alaska from Russia. The gold rush, started in 1870, led explorers, settlers, and missionaries to arrive in greater numbers. For many Native communities the introduction of commercial whaling and natural resource markets provided an economic opportunity to communities experiencing the impacts of settler colonialism and threats to traditional lifeways and survival.

Many New Bedford whaling vessels voyaged to the North Slope of Alaska. The first US whaler crossed the Bering Strait to hunt bowhead whales in the Arctic in 1848. The peak season was 1852, when 2,682 bowhead whales were killed. Between 1885-1905, San Francisco became the largest whaling port in the world. East Coast fleets would overwinter there or on the North Slope at Utqiagvik (Barrow) to await the spring whaling season. Some New Bedford whalemen settled in Arctic villages, and some North Slope residents trace their ancestry to the "Yankee whalers." Iñupiaq were actively recruited as whalemen and crews on the boats, engaged in brisk trade with whaling crews, and helped supply the fleet with food. Today, they continue to practice subsistence whaling.

A steel-blade dagger from circa 1780 was traded with the Haida on the Northwest Coast. An unknown Haida maker then created a special pommel of whale baleen with a thunderbird head inlaid with abalone. The binding is made of seal hide. This embellished dagger became an important personal item, likely representing protection and facilitating survival for its owner and their community. Similarly, sometime around 1895 a Kwakwa̱ka̱'wakw individual in British Columbia either purchased or traded for a Stevens’ Favorite Rifle (made in Massachusetts). They carved and decorated this prized possession with inlaid abalone formline imagery. While both kinds of weapon register violence, they also supported subsistence, defense, and survival. Their customization implies the importance of these items to their owners and demonstrates how adaptation meant cultural continuance and physical survival.

Excerpt from Ravens and Eagles, Season 1, Episode 4, “Argillite Carver.”

Christian White carves intricately designed and elaborately executed traditional Haida stories in argillite, a black slate found only on Haida Gwaii. He is a direct descendant of Charles Edenshaw, and his father Morris White taught him how to express his culture through his creative gifts. In this episode, White works alongside his apprentices in his studio in Massett, Haida Gwaii.

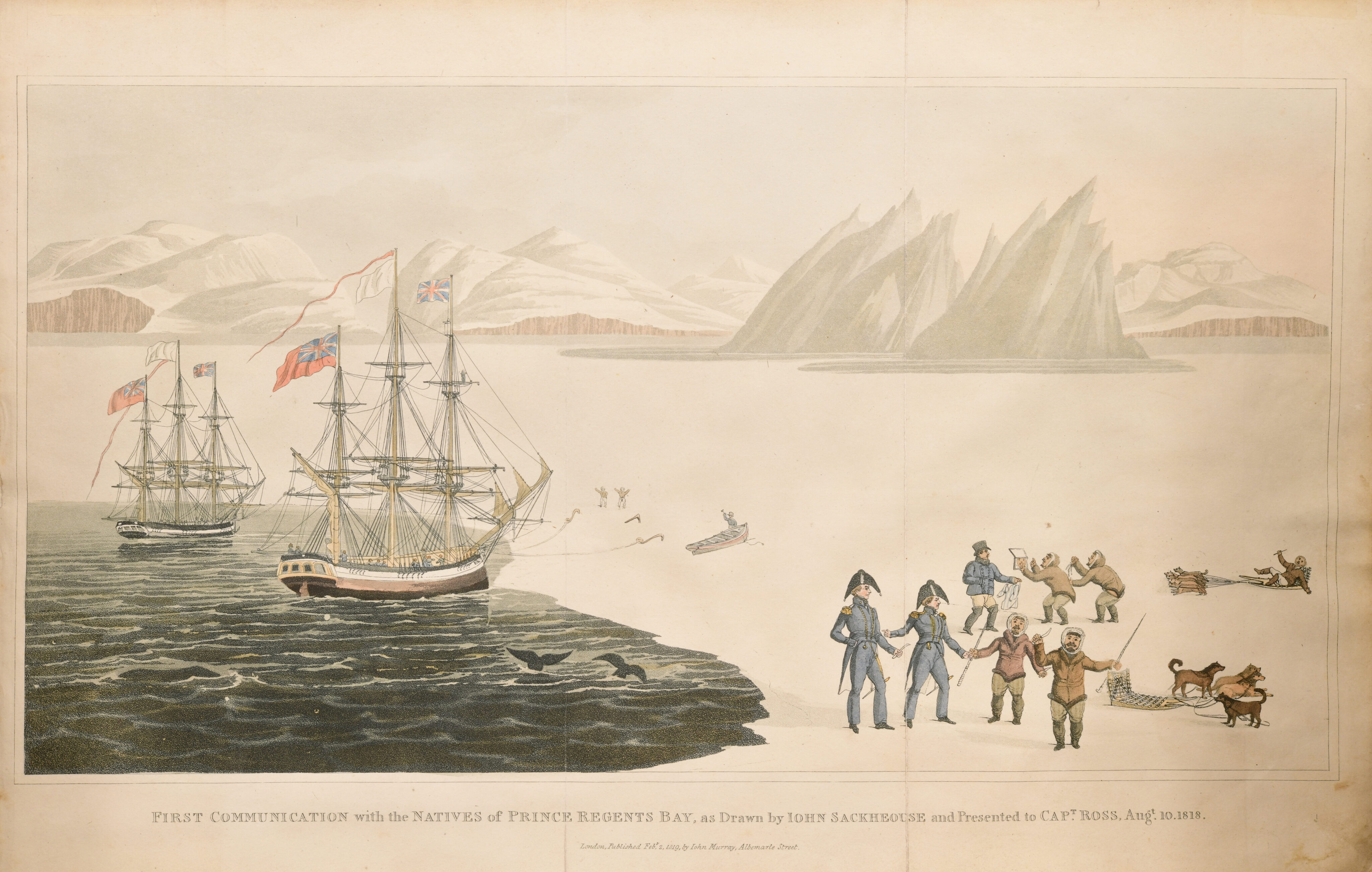

Seeing Each Other | Seeing Ourselves - Arctic

US and European prints, paintings, and publications demonstrate an interest in solidifying the myth of discovery and conquest of the Pacific world through visual means. Such scenes constructed visual imaginaries about far-off territories colonial audiences would never physically reach, and regularly primitivize Indigenous cultural groups and traffic in Native stereotypes. Rarer examples turn the mirror back, revealing how explorers, whalers, and other colonizers were seen and recorded on the visual and material culture produced by Indigenous makers.

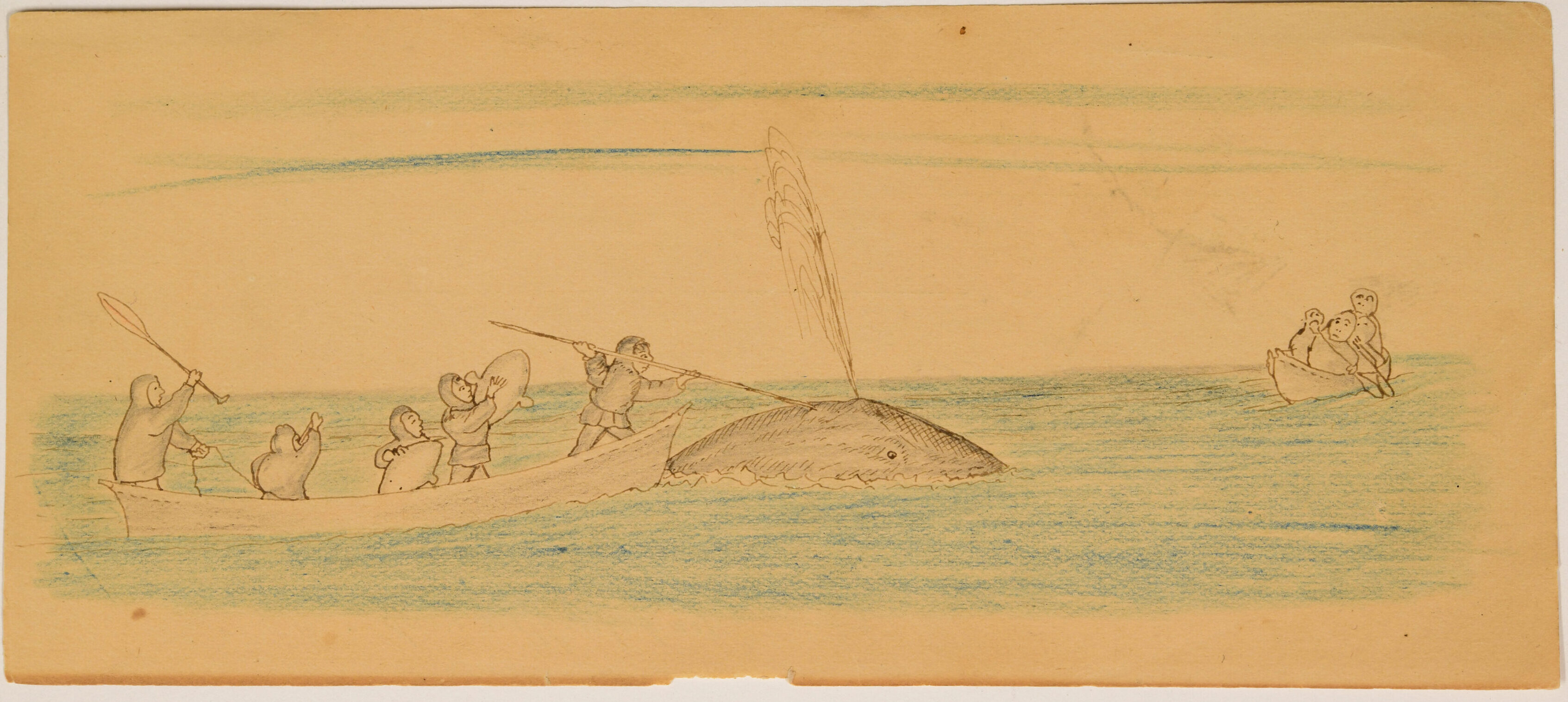

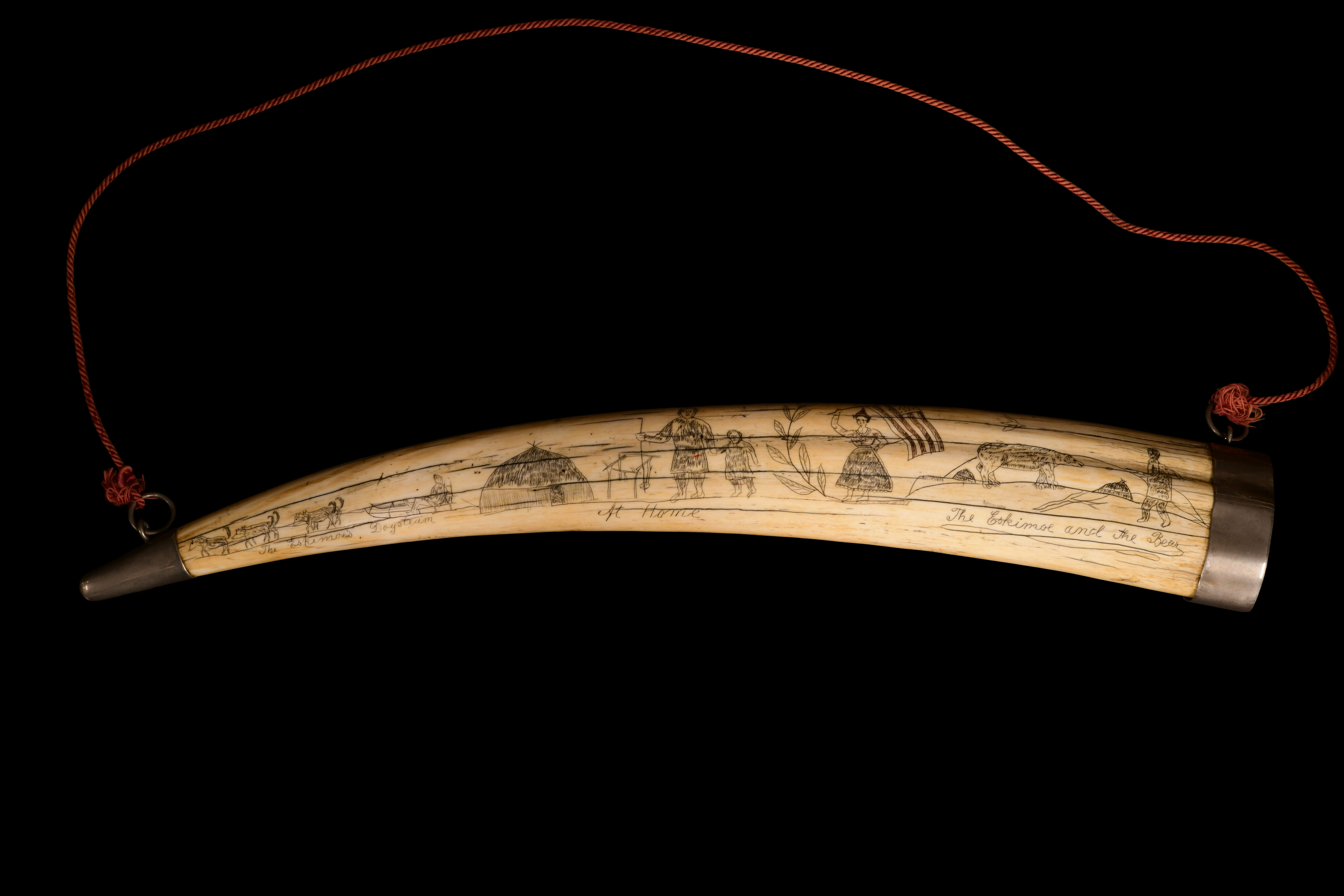

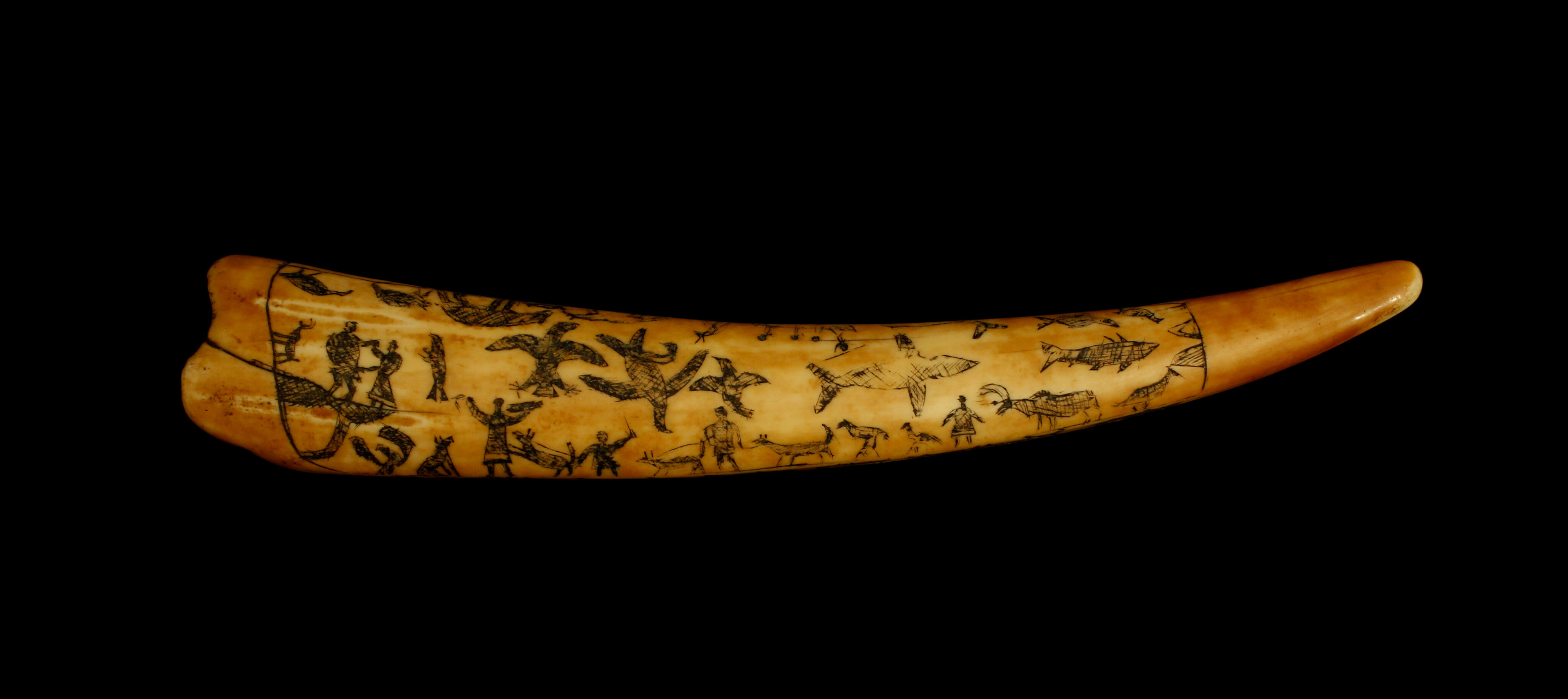

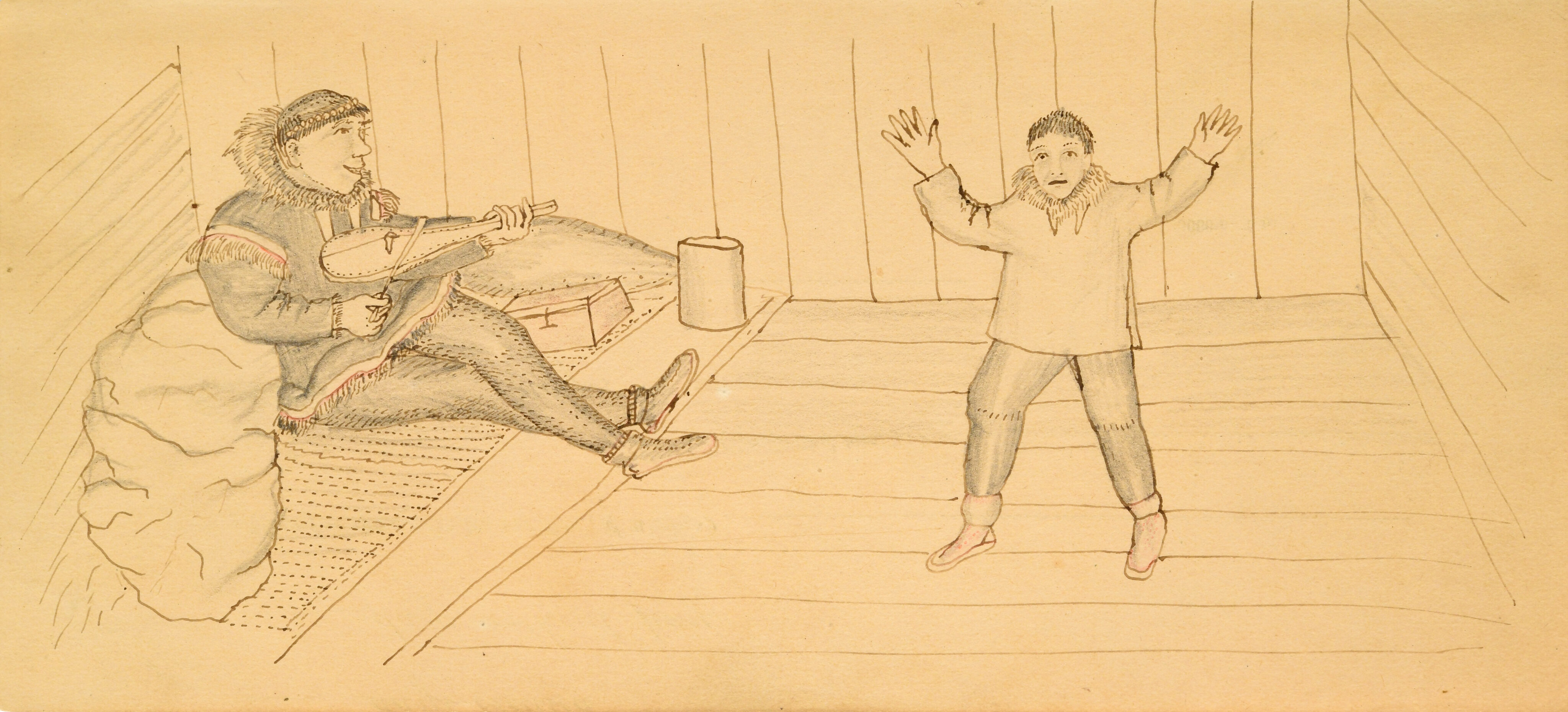

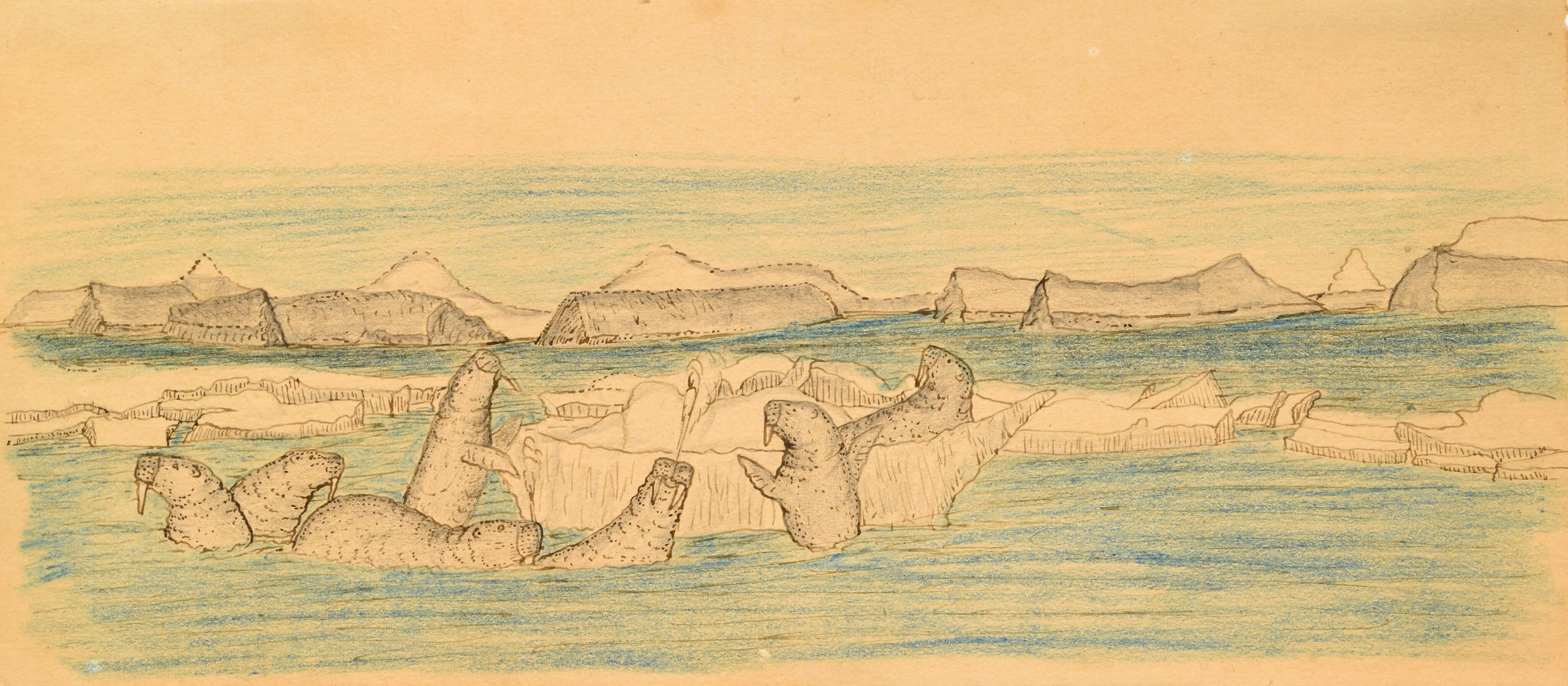

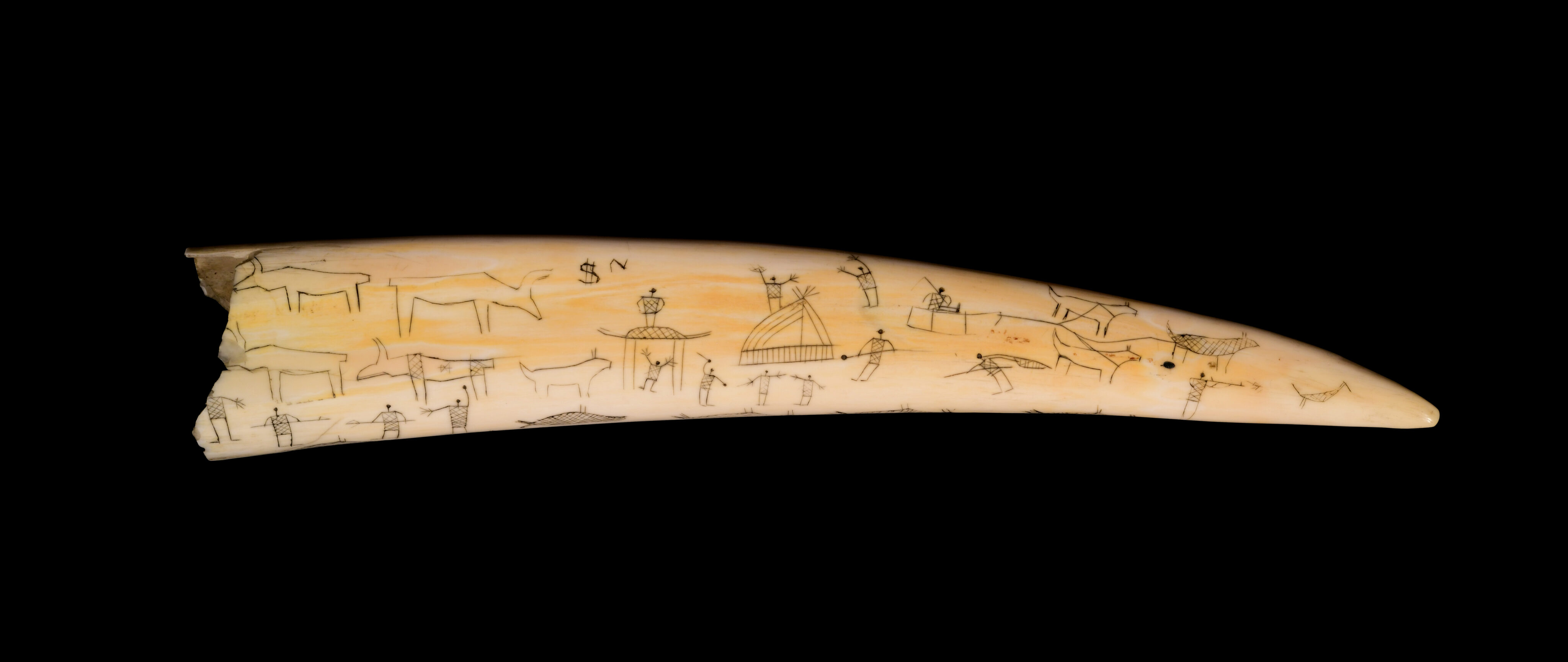

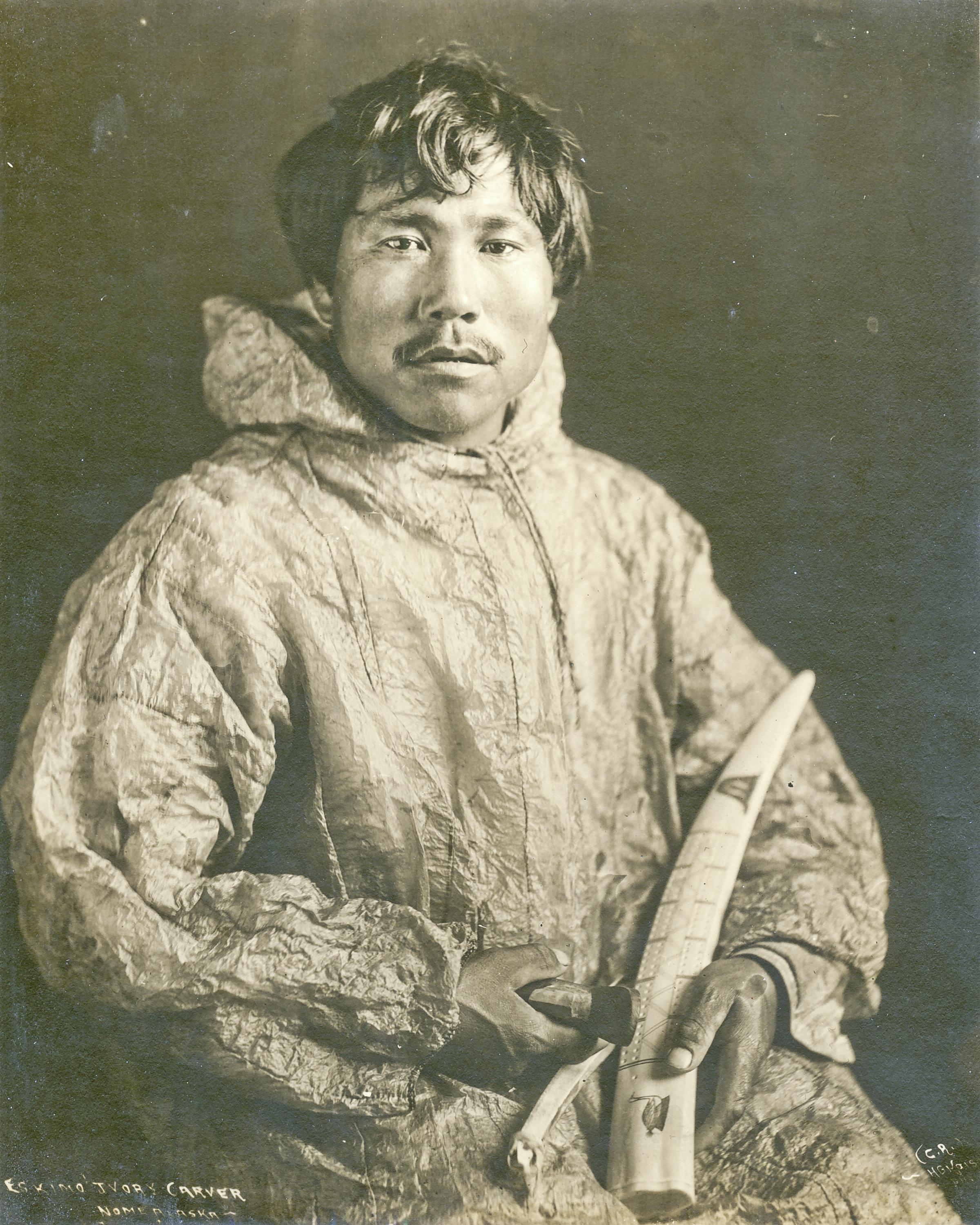

A walrus tusk shows reindeer, seals, and whales, Iñupiaq hunters with firearms on dog sleds and fishing from umiaqs, and US whaling ships and whalers. A group of mission school drawings by Iñupiaq children record the intimacies of community life. These illuminate communities from within, presenting a rich counterpoint to traditional settler colonial histories, and — in so doing — they emphasize survivance and futurity. Such objects question the directions of the gaze (who looks at who), and reframe cultural contact as a space of negotiation and exchange that is not in the past but continues today.

Ibeivik: June Birth Time

When animals give birth

Upinagaq: Summer

Qusrimmak: Wild Rhubarb

blueberries, salmonberries,

crowberries, fresh shoots

of fireweed to eat,

her/ my nipples hard like hoary

marmot teeth, she/ I smell/s

of stinkweed, willow leafs,

tree roots, hailstones.

It’s her/ my time to carve

oars to make her/ my

umiak or kayak skin boat.

Ibeivik: June Birth Time

When animals give birth

Upinagaq: Summer

Qusrimmak: Wild Rhubarb

blueberries, salmonberries,

crowberries, fresh shoots

of fireweed to eat,

her/ my nipples hard like hoary

marmot teeth, she/ I smell/s

of stinkweed, willow leafs,

tree roots, hailstones.

It’s her/ my time to carve

oars to make her/ my

umiak or kayak skin boat.

The Nome School and Inuit Print Collectives

Items made for the souvenir trade in Nome, Alaska, for settlers and tourists drawn by the 1898 Gold Rush demonstrate creative adaptations by Native artists to meet changing market conditions. The “Nome school” of Iñupiat carvers incised walrus tusks with figurative imagery of arctic animals and quirky decorative motifs, including oversized houseflies, human hands, and exotic non-native species (like Indian elephants), making sly commentary on the illusionism of carving, the physical material support, and the “trade” in “Native” souvenirs that supported their livelihood.

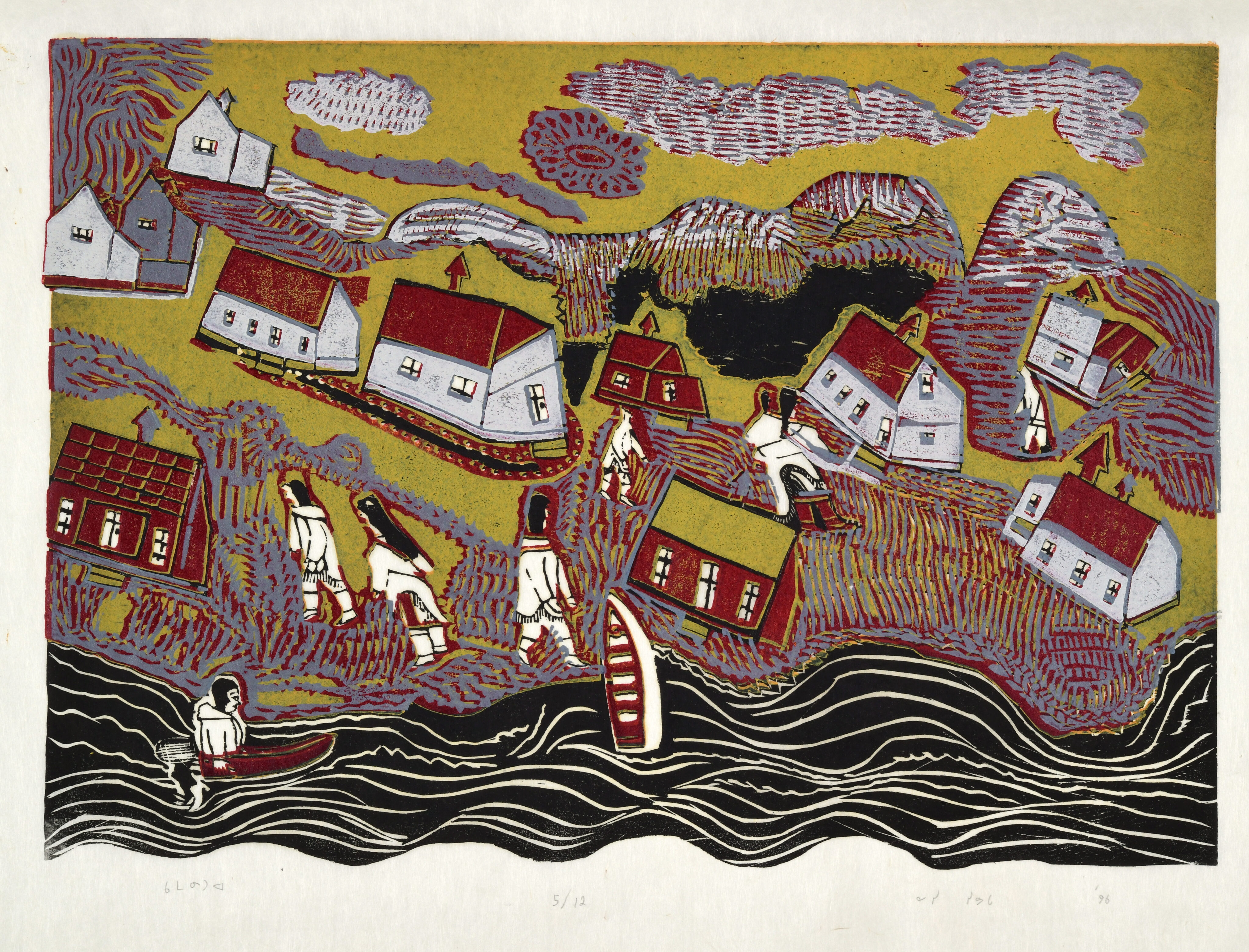

In the 1950s, the Canadian government encouraged eastern Arctic Inuit communities to take up printmaking as an economic and creative outlet. Graphic art was historically rare in the region, but Inuit artists adapted to the new medium, which had similarities to carving. They pictured daily life, cultural stories, and events. Printmaking cooperatives like Cape Dorset and Pangnirtung in Nunavut continue the tradition today.

Arctic Song, 2021

In this six-minute short, Inuit artist, storyteller and co-director Germaine Arnattaujuq (Arnaktauyok) depicts Inuit creation stories in all their glory. Arctic Song tells stories of how the land, sea and sky came to be in beautifully rendered animation. Telling traditional Inuit tales from the Iglulik region of Nunavut through song, the film revitalizes ancient knowledge and shares it with future generations. Canadian National Film Board.

Director: Germaine Arnattajuq, Neil Christopher, Louise Flaherty

Writers: Germaine Arnattajuq, Neil Christopher, Celina Kalluk

Inuktitut Language Specialist: Monica Ittusarjuat

Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada

SEEING EACH OTHER | SEEING OURSELVES - Pacific

US and European prints, paintings, and publications demonstrate an interest in solidifying the myth of discovery and conquest of the Pacific world through visual means. Such scenes constructed visual imaginaries about far-off territories colonial audiences would never physically reach, and regularly primitivize Indigenous cultural groups and traffic in Native stereotypes. Rarer examples turn the mirror back, revealing how explorers, whalers, and other colonizers were seen and recorded on the visual and material culture produced by Indigenous makers.

An 1880s hiapo from Niue is signed and includes a whale ship with human figures on the deck and masts. It is installed alongside a contemporary hiapo made in response. A gift album of albumen photographs of Hawai'i made by Elizabeth Keka‘aniau Laʻanui Pratt (1834-1928) and sent to a sister in 1889 reveal daily life amid the pressures of colonialism. An 1830 print of Lahaina made by Kepohoni in a missionary print studio shows the island of Maui copied after a painting by a female missionary. Such objects question the directions of the gaze (who looks at who), and reframe cultural contact as a space of negotiation and exchange that is not in the past but continues today.

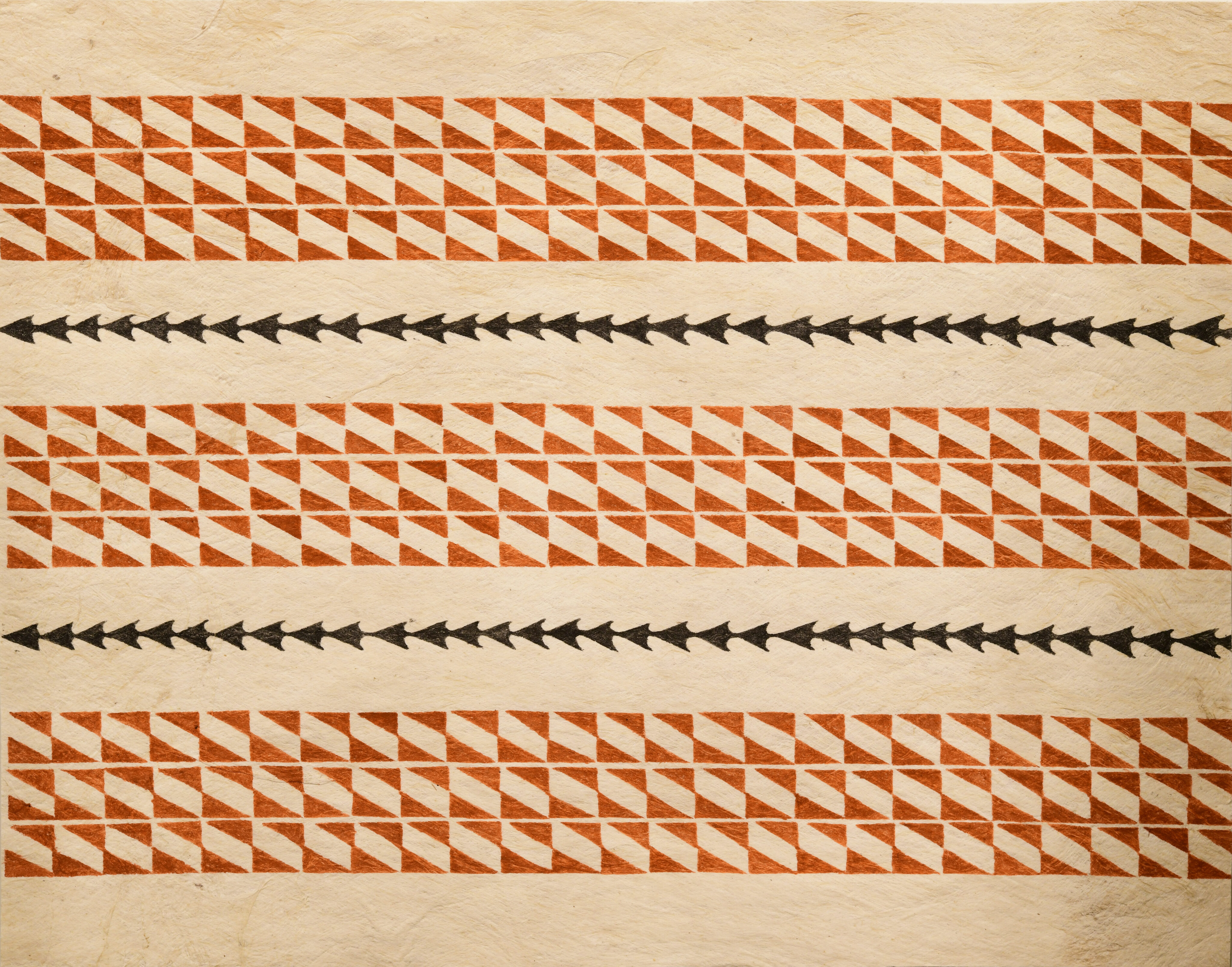

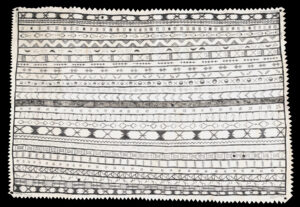

Decorated barkcloth called tapa are made across Oceania. This versatile fabric is used for clothing, mats, memorial, and ceremonial purposes. Each community has a word for the craft. In Niue, it is called a Hiapo. The bark cloth featured here was made in Niue between 1880 and 1900. It illustrates local plants and seeds, traditional patterns, and a Western European or American square rigged sailing ship with people climbing the rigging. Biological forms around the ship may be crayfish in tide pools that lived around the edges of the island. This Hiapo illustrated a period of change in Niue, when travelers and missionaries arrived. The creation of Hiapo decreased dramatically by 1900 with the introduction of cotton. Recently, contemporary practitioners have begun making Hiapo again.

My Hiapo was formed using traditional techniques and materials incorporating newly developed patterns that celebrate and depict ocean life from a whale’s perspective. The work is composed into the long lines familiarly found on throat of the Blue whale, also representing the long movements of migration and the sound of their voices that can carry far into the deep ocean. The dark strip in the middle of the work is made from whale oil that was gifted to me by a Māori artist and soot from the tuitui seed harvested in Niue. These special materials combined make a deep black that represents part of the whale’s birth in the poem written as a voice for this Hiapo. Within the lanes of twenty-four patterns you are presented with possible thoughts, perspectives, and visual symbols that a whale may see in the ocean next to the island of Niue. Specific fish species that are commonly known in Niue, reference to the land shapes, and weather patterns attempt to connect the environmental impacts on the whales’ experience in the ocean. Niue, where I feel safe draws attention to the preservation efforts and conservation techniques used in Niue as a leading place for organic farming, safe fishing practices and as guardians of whales.

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss, multi-disciplinary artist of Māori (Ngā Puhi, Tainui) and Niuean descent

How Hiapo is Made

Harvest

Hiapo is created by beating the inner bark of a tree, in Niue different trees are used for Hiapo such as the Ata, Banyan or Hiapo tree which is more commonly known as the paper mulberry. The tree is cut from the base of the trunk, the branches are removed close to the trunk, and the inner bark is carefully stripped. A line is cut down the length of the trunk and the inner bark is fully removed in one strip.

Beating

The inner bark strip is then between with an Ike (beater) on a Tutua (anvil) these tools are made with a hard wood making it easy to beat the tough inner bark of the trees.

Water is used to help the bark spread during the beating process and the bark is likely to spread more than three times its original size. Different thickness and surface textures are dependent on the tools used and the desired outcome of the maker.

Pasting

To create a large Hiapo, pieces are joined by pasting them together using a glue made from the root of the tapioca plant.

Painting

Using soot from the tuitui (candlenut) an ink is made to decorate the Hiapo and a dried Pandanus seed is used as a paint brush. The artist will choose different traditional motifs and symbols to create a composition suitable for the purpose of the Hiapo.

NIUE WHERE I FEEL SAFE

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss, multi-disciplinary artist of Māori (Ngā Puhi, Tainui) and Niuean descent

Sina ma le Tuna (Sina and the Eel), directed by India Taberner, 2022. Masina Studios.

An animated retelling of the Samoan story of Sina and the Eel about the origin of the coconut.

I Am but a Little Woman, directed by Gyu Oh, 2015. Nunavut Animation Lab, National Film Board of Canada.

Inspired by a 1927 Inuit poem, this animated short evokes the beauty and power of nature, and mother-daughter bonds. As her daughter looks on, an Inuit woman creates a wall hanging filled with images of the Arctic landscape and Inuit symbolism.

Courtney M. Leonard, “ReelNative,” 2008. In American Experience, Season 21, Episode 5, PBS.

Courtney M. Leonard reflects on her community’s thoughts when a 60-foot finback whale washed up on Shinnecock land in eastern Long Island after being struck by a ship in April 2005.

Artist Portrait: Courtney M. Leonard, Conversing in Clay, 2022. Nandi Jordan, LACMA Productions, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In this video, artist Courtney M. Leonard discusses her relationship to clay and her basket-like art forms called “Abundance,” featured in her BREACH log book installations. BREACH: Logbook 24 | SCRIMSHAW is currently on view in the second floor Center Street Gallery here at the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

This program and corresponding exhibition and publications and contributions was made possible through major support from The Henry Luce Foundation and The Terra Foundation for American Art; and contributions from The CIRI Foundation, The Decorative Arts Trust, the Jessie Ball DuPont Fund, Furthermore: a program of the J.M. Kaplan Fund, and a National Maritime Heritage Grant, administered by the National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, through the Massachusetts Historical Commission

The Wider World & Scrimshaw is organized by the New Bedford Whaling Museum

Lead Sponsors:

Major sponsors:

Generous sponsors: